Today, December 12, is the feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and in honor of La Virgen, Mexicans and Mexican Americans will be gathering to celebrate mass, recite novenas, make music, dance, and march in the streets. But the reality is that devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe is not limited to this day only—La Virgen is such a central figure in Mexican cultural and religious life that she is present and powerful every day. This is especially true for women, who find in La Virgen the possibility of transforming sorrow and pain into strength and hope.

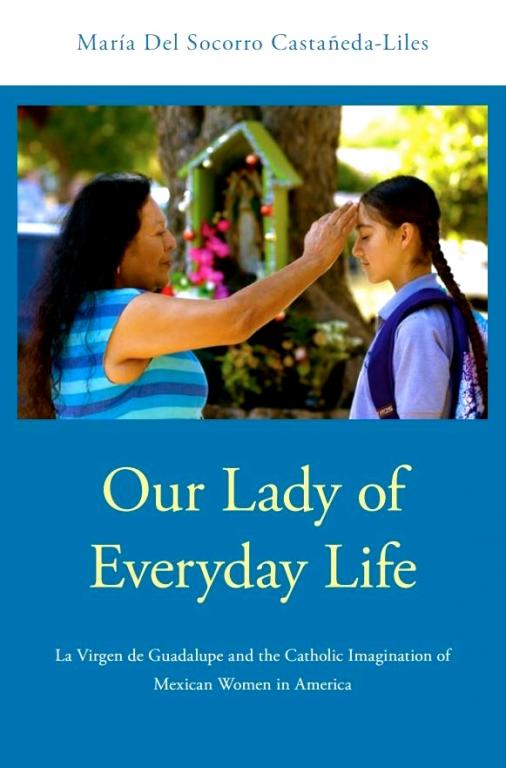

To understand the significance of La Virgen in the lives of Mexican Catholic women, I interviewed Dr. María Del Socorro Castañeda-Liles, author of Our Lady of Everyday Life: La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic Imagination of Mexican Women in America (Oxford University Press, 2018) and “Our Lady of Brave Change: Spiritual Imagination at the Heart of Strength & Resilience.” Dr. Castañeda is Co-Founder, with her teenage daughter Lupita, of Becoming Mujeres a firm that helps Latina mothers and daughters translate cultural expectations into opportunities. A Ford Foundation fellow whose research has been supported by the Hispanic Theological Initiative and the Louisville Institute, Dr. Castañeda is a former Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Santa Clara University and a sought-out speaker and expert in the areas of Mexican Popular Catholicism, Our Lady of Guadalupe devotion, LatinX cultural expectations, mother-daughter communication, and teenage girls and social pressures.

MB: Tell me about the book. What is your argument?

MSCL: My book is one of the first sociological studies and the first intergenerational analysis of Mexican origin women and Catholicism. As such, it is the first in-depth analysis of how women from three different generations are socialized into Mexican Catholicism and devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe or La Virgen as the faithful refer to her.

It is based on an in-depth study of three generations of working-class Mexican-origin women between the ages of 18 and 82—young college women, mothers, and older women. I examine the Catholic beliefs the women inherit from their mothers and how these beliefs become the template from which they first learn to see themselves as people of faith.

I argue that through the nexus of faith and lived experience, these women develop a type of Mexican Catholic imagination that helps them challenge the sanctification of shame, guilt, and aguante (endurance at all cost), allowing them to transgress strict notions of what a good Catholic woman should be while retaining life-giving aspects of Catholicism. This transgression is most visible in their relationship to La Virgen, which is fluid and deeply engaged process of self-awareness in everyday life.

MB: How did you choose the title, Our Lady of Everyday Life?

MSCL: I chose this title because Our Lady of Guadalupe is indeed in the everyday life of the women who participated in my study. Our Lady of Guadalupe not only exists in material culture. That is, between the crisp folds of prayer books which have been worn out by age; in the worn out beads of a rosary that has witness moments of desperation and plea; or in the estampitas and medallas (prayers cards and medallions) given by mothers to their daughters for protection as they embark on their college journey. The relationship that they have with her takes shape in real-life situations.

When they were children, La Virgen came to life every time they witnessed their mothers and abuelitas (grandmothers) talk to La Virgen or light a candle to her for a friend or family member who was about to cross the border. As they grew and matured, they developed a more sophisticated understanding of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s significance in Mexican Catholicism. They understood La Virgen to have the capability to transform their sorrows and pain into hope and resilience. Young women talk to her as they pray for mental clarity before taking an exam. Mothers talk to her as they wash dishes or do other house chores, affirming that La Virgen doesn’t mind because she is a mother just like them and understands how busy they are. They share with her about what brings them joy or worries them. Older women talk to La Virgen as they go through their day and pray for the safety of their children and grandchildren. They see La Virgen as their heavenly mother who accompanies them.

What is essential to understand is that while the women may be handed down conceptions of La Virgen as submissive, all-forgiving, and all-accepting, this does not necessarily translate into submissive, all-accepting, and all-forgiving women. Ultimately, women re-craft the social subjectivity of La Virgen as part of their adaptation and resistance to the structure of opportunity they experience in the United States. In their eyes, Our Lady of Guadalupe calls women to act and not endure situations that attempt against their human dignity.

MB: Your decision to consider religious experience across multiple generations is a unique contribution of your book. How does studying Catholic life inter-generationally allow us to understand Catholic life, especially Mexican American Catholic life, in a new way?

MSCL: As I mentioned above, it allows us to come to a more in-depth comprehension of women’s Catholic upbringing. More specifically to the Catholic Mexican American/ChicanX experience, the childhood memories of the three generations of women, reveal the life-giving aspects that come with growing up Catholic. Some of these memories include listening to the stories of miracles granted, las posadas during advent, and las mañanitas (morning serenade) to Our Lady of Guadalupe on December 12th.

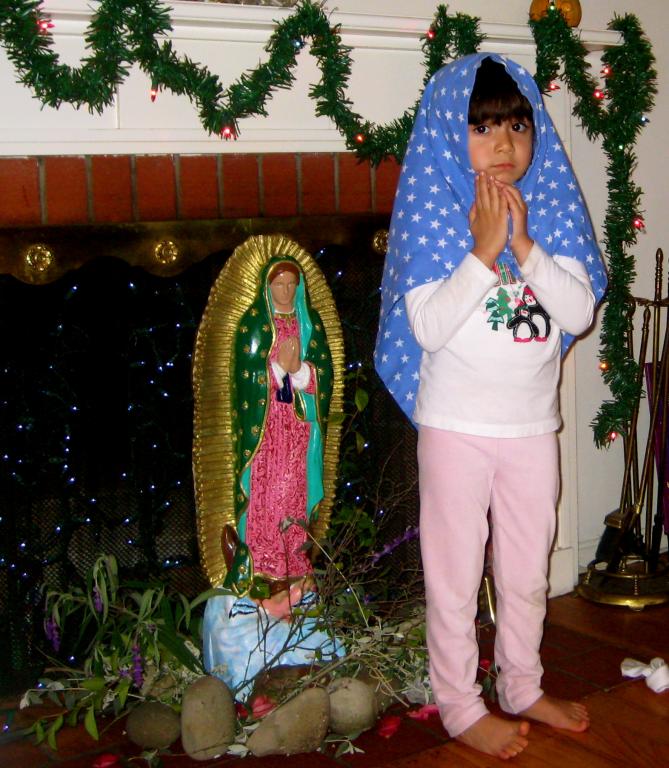

These traditions help solidify a Mexican Catholic identity early in the lives of children. They learn about La Virgen from their mothers, abuelitas (grandmothers) and tias (aunts). In other words, devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe is passed on through the women in the family. From their mothers, they learn to see Our Lady of Guadalupe as their heavenly mother, someone they could turn to in moments of despair. On December 12th, her feast day, they feel her particularly closer as La Virgen comes into their lives through songs in her honor, flower offerings, the traditional mariachi serenade at their local church, and family traditions like home altars and dressing girls and boys in traditional indigenous clothing for the special mass on her feast day.

Just as there are many life-giving aspects to growing up in a Mexican Catholic family, there are others that are death-bearing. The Mexican American/ChicanX Catholic experience is not an either-or, but a both-and way of life. As my book demonstrates, as girls enter puberty, the Catholic imagination that mothers pass on to them dresses their bodies with sacralized silence. For example, most Mexican-origin women (and Latinas in general) feel that their mothers do not understand them. It does not matter if their daughters are 15, 25, 40, married or single, mothers often criticize the length of their skirts and dresses, how low their neckline is, how much makeup they put on, or heaven forbid, how hociconas (big mouth) they are. Their comments trigger in these women a boiling urge to judge, reject, or in some cases, insult their mothers because, from their point of view, they are too anticuadas (too old-school or too traditional).

While these reactions from mothers may be the case across race and ethnicity, Our Lady of Everyday Life argues that this type of silence is rooted in what theologian Virgilio Elizondo calls the sense of shame imposed on Latin America’s conquered people by the Catholic Church. Unfortunately, this sense of shame continues to be one of the most devastating consequences of the conquest because it cuts across generations. Furthermore, it not only has a particular class, race, and color; it is also gendered, relegating women to a life of complete or selective silence about their bodies, sex, and sexuality. To this day, the Catholic Church continues to perpetuate this sense of shame, placing women in the role of involuntary perpetrators of their own mental and physical subordination as mothers feel nervous to talk to their daughters about puberty, sex, and sexuality. Consequently, some mothers choose to remain silent.

Some might argue that culture, like religion, is equally implicated. However, let us not forget that with the conquest came the imposition of a Catholic worldview where women, particularly Nahuatl women, were severely subordinated. With the passing of the centuries, aspects of this Catholic worldview were sanitized, if you will, and were passed as a secular culture with no association to Catholicism. However, as one of the women I interviewed told me, our Mexican American/ChicanX experience is a café con leche (coffee with cream) reality. That is, culture and religion cannot be separated; they are intractably bound.

MB: How does your book shed light on how Mexican American women might be grappling with difficult contemporary issues, such as feminism and perhaps also immigration and racial identity?

MSCL: The type of consciousness development that I observed in the lives of the women conveys that the liberating acts of these women can be traced to Catholic devotionalism, which has horizontal and vertical underpinnings. When the horizontal (their sense of their own agency, here in their lived earthly experience) and the vertical (their faith in the heavenly power of Our Lady of Guadalupe) intersect a certain type of feminist consciousness emerges—what I call a (fe)minist consciousness where fe literally means faith. This (fe)minist consciousness allows them to develop strategies for transcending oppressive situations and limiting belief systems. I saw this in particular among the mothers and young college women generations.

Within this (fe)minist consciousness, the relationship that the women have with Our Lady of Guadalupe is continuously shaped by women’s sense of self, life experiences, and devotion to her. While this relationship anchors Our Lady of Guadalupe in Catholicism, it nevertheless is articulated in ways that unbind La Virgen from the more restricting aspects of Catholic teachings about and for women. In La Virgen they find the courage to speak up against physical violence in spite of their vulnerable legal status in this country. They take pride in sharing the same skin color as La Virgen. In La Virgen Morena (the brown virgin), they find racial and ethnic affirmation, peace in the midst of their personal struggles, strength to act rather than to endure, and humility that does not embrace humiliation. Our Lady of Guadalupe for these women is Our Lady of Everyday Life and brave transformations.