Today we’re happy to welcome Joey Cochran to the Bench. A PhD candidate in church history at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Joey teaches adjunct at Wheaton College and Trinity Christian College. You can follow him on Twitter, where a seminary president’s tweet got Joey thinking about what Christians mean when they say someone is a “heretic.”

2019 ended controversially for many “evangelical” Christians connected to the Southern Baptist Church (SBC) and its seminaries, as well as for those shaped and influenced by the theology of James Cone, who passed in April 2018.

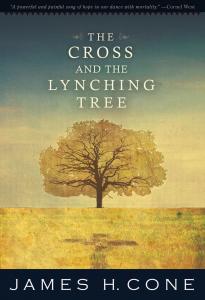

On December 29, Danny Akin, President of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, asserted that James Cone was a heretic, based on the Union Theological Seminary professor’s views of atonement, which are best conveyed in two of Cone’s works: A Black Theology of Liberation and The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

https://twitter.com/DannyAkin/status/1211426030981992449

The public conversation that resulted from Akin’s tweet was fascinating. On one side, intellectually savvy influencers and students put forth arguments either for Cone’s orthodoxy or in support of Akin’s charge that Cone was a heretic. On the other hand, there was a slew of gifs and name calling, simply asserting Cone’s heresy and taking down those who came to Cone’s defense. Southern Baptists base the charge of heretic on doctrine, whereas some notable African American scholars and influencers pinpoint the possibility of White Supremacy being in play. The exchange has since produced Malcolm Foley’s thoughtful article “On the Assault of James Cone & Liberation Theology”, which supports Cone’s orthodoxy.

Even more particularly, the fact and the ways in which his Blackness shaped, formed and necessitated his theology. https://t.co/INiD7vcK6i

— Rev. Malcolm Foley, PhD (@MalcolmBFoley) December 31, 2019

What is a Heretic?

One idea that the exchange called into question included the matter of what is a heretic? This question is beneficial because it orients everyone to why the conversation became so emotionally charged for many and seemingly trivial to others.

The Greek term hairesis is found in 2 Peter 2:1 and commonly refers to a sectarian group, either political or religious, that has deviated from the majority. The charge of heresy over the long history of the Church involved denial or flagrant distortions of essential doctrines of the Church—particularly involving the Trinity, Christology, and the Canon of Scripture. It was most commonly understood that heretics were baptized confessors of Christ and members of the Church that had fallen away from orthodoxy into false teaching. Heretics normally had teaching authority in the Catholic Church. Because the Catholic Church and its bishops had been given “the keys” to bind and loose matters on earth and in heaven (see Mt 16:19), they were responsible for absolving sin for the penitent and enforcing discipline for unrepentant heretics.

The eras of the Apostolic Fathers and Apologists were preoccupied with persecution and martyrdom from outside the Church. Nonetheless, church leaders such as Tertullian, Irenaeus, and Clement of Alexandria condemned groups for heresy and individual false teachers as heresiarchs and heretics. For these apologists, the charge of heresy and heretic was the shibboleth that distinguished the counterfeit groups and teachers from the true church and its teachers. Commonly known heretics of the Early Church include Valentinus, Arius, Nestorius, and Apollinarius. Of course, during the Arian controversy Athanasius was deposed and forced into exile five times, famously penning Athanasius Against the World as his argument against Arianism.

Throughout much of church history, the charge of heresy was not taken lightly. For those who underwent condemnation as a heretic, it meant excommunication from the Catholic Church. But false teaching did not just have bearing on the ecclesial order but also civil order. The charge and consequence of heresy were handled by the formal and magisterial authority of the Catholic Church, but excommunication had physical and spiritual consequences. They were exiles from the church militant on earth, and they were spiritually exiled from the church triumphal in heaven. Heretics were commonly condemned to execution and it was understood that they were destined for eternal separation from God in heaven. Those who wished to escape the consequence of execution fled as exiles into the wilderness, or at least made sure that they were safely outside the reach of the civil authorities executing this order.

Women, Jews, and Muslims during the Middle Ages were executed for the charge of being a witch or for failing to submit to the magisterium of the Catholic Church and its teaching. Ethnic cleansing, removal of civil subversives and undesirables in communities, or land-grabbing was facilitated under the guise of the charge of heretic by the Catholic Church during the terrible period of the Spanish Inquisition.

The Reformation of Heretic

When the Protestant Reformation occurred, calling someone a heretic itself underwent reformation. On June 15, 1520, Pope Leo X issued the papal bull Ex Surge Domine against Martin Luther. The Protestant reformer understood the tradition of the charge of heretic and the gravity of his circumstance. He was endangered physically and spiritually. Nonetheless, on December 10, 1520 Luther gathered a number of faculty and students at the Elster Gate at Wittenberg for a small bonfire, where he burned the papal bull as a major act of defiance.

This event proved to be a pivotal moment in Church History for the reformation of heresy. Luther’s conviction is that if he was in error and the Roman Catholic Church was the One, True Church, then this excommunication had a binding power over his involvement in the church militant and triumphal. However, Luther’s reformational tenet of Sola Scriptura relocated ultimate authority in Scripture rather than the Church. Authority was now based on individual private judgment through reason and conscience.

The power of “the keys” was now loosed from the exclusive authority of the Catholic Church and put into the hands of anyone who interpreted doctrine correctly from Scripture. Thus, during the Protestant Reformation you now have Swiss Reformers in Zurich drowning Radical Anabaptists and Genevan authorities burning the Spaniard Michael Severtus for denying the Trinity.

The Evolution of Heretic

Things, of course, get dicey on cleanly understanding the charge of heretic. Around the time people started to embrace scientific evolution, they also started to evolve terms that had a different meaning in the enchanted world of antiquity.

Arguably, the first heretics in America became the first Baptists in America. Anne Hutchinson and Roger Moore became embroiled in the Antinomian Controversy stirred up by Congregationalist pastors John Cotton, Thomas Shephard, and Thomas Hooker from 1636-1638. Moore and Hutchinson were exiled to Rhode Island as a result of their part in the controversy. On the other side of the Atlantic, Janet Horne was the last person executed as a witch in 1727 in Scotland. Likewise, the last to be executed in the Roman Catholic Church for heresy was schoolmaster Cayetano Ripoll, who was hung in 1826 for the charge of Deism.

Throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries the charge of heretic fell out of practice. Groups and individuals were less likely to receive the charge of heresy and heretic. For instance, Jonathan Edwards referred to the Deists as “ben’t like the heretics” in “Sermon 24” of A History of the Work of Redemption (WJE 9, 432). Yet, that’s not the same thing as being heretics. The story of J. Gresham Machen’s classic condemnation of liberalism in Christianity and Liberalism is an interesting comparison to the Cone and Akin controversy. Machen’s book was published in 1923 during the fundamentalist/modernist controversy. Machen critiqued Harry Emerson Fosdick and other liberals, inviting them to leave the Presbyterian Church. But he did not call liberalism heresy or Fosdick a heretic. It’s interesting to consider the restraint that Edwards and Machen demonstrated in reference to the charge of heretic.

Those from higher church traditions that have formal practices for ecclesial discipline—such as the Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, and Presbyterian traditions—still consider groups or individuals guilty of material and formal heresy. However, since Vatican II, even the Roman Catholic Church prefers to refer to the Protestant heretics as separated brethren. And, well, no one is burning or hanging anyone these days. It seems humans are more civil today and subversive Christian teaching is much less a threat to civil order.

Those from a lower church tradition, like the Southern Baptists and particularly President Akin, take the charge of heresy and heretic less seriously. For them, heresy really functions as name-calling and a way to taint the reputation of liberal theology. The charge is reduced to a populist and democratized power that merely affects reputation and creates a stigma to a group. Heresy is only a material charge and no formal charge may be made. Southern Baptists leverage the charge of heresy and heretic in some sort of sectarian function, which separates the true church from the false.

A Post-Modern Heretic

Regardless of how you look at it, the definitional evolution of the term heretic as received by Southern Baptists can only be supported through George Lindbeck’s adoption of Wittgenstein’s language games for ecclesial communities. Groups like the Southern Baptists have particular words that have distinguished meanings from the way other communal groups have defined those terms. Some of this is as a result of organizational and ecclesial limitation. In a sense, a Southern Baptist understanding of the term heretic is grounded in the Post-Modern deconstruction of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. It’s an adaptation of critical theory and perhaps just as liberal as Cone’s view of the atonement.

Heretic is a term that has been detached from its historical understanding, and its value-laden power has been stripped. After all, there is no Southern Baptist magisterium. President Akin’s charge that Cone is a heretic has no formal power behind it because it is one individual’s judgment and conscience based on his interpretation of Scripture.

Nonetheless, Akin’s series of tweets and the ensuing conversation produced a response that could be compared to a Trump Twitter debacle. This is because Akin’s function in the SBC community adds clout to the charge. Now, Akin is no Trump, and I sincerely believe that his condemnation is detached from any view of race. Rather, it is strictly built on a doctrinal belief regarding the atonement.

All that said, the entire event calls into question whether we should call anyone a heretic in 2020 and what value the charge has today? Is it merely name-calling when done apart from a formal process? Does it have any of the physical and spiritual consequences it once did during the long history of the Church?

And if this is the case, whether by intent or not, could some interpret the charge of heretic as color-blind language retrieved from antiquity? And if the charge is brought from a group that has no formal due process for such charges, could some make the comparison to the charge of heresy with the practice of lynching, a practice that also lacked due process?

These are unfortunate corollaries, but they are reasonable inductions, especially in light of Cone’s significant work on the history of lynching in America and its traumatic implication for theological interpretation in black theology.