Howard Jones was a Christian and Missionary Alliance pastor in Cleveland. In the late 1950s he began to syndicate Smoot Memorial Alliance Church’s Sunday morning services. These broadcasts eventually made their way to Africa, where they enjoyed immediate popularity on a Christian radio station named Eternal Love Winning Africa (ELWA).

Africans were delighted to hear an African American on the airwaves for the first time. Sudan Interior Mission soon invited the young preacher with a big voice and animated hand gestures to conduct evangelistic rallies in Monrovia, Liberia. He arrived in 1957 to “great fanfare.” “Wherever we went,” Jones recalled, “people would squeeze our hands tightly, pull us toward themselves and say, ‘Where have you been? We’ve seen the white missionary, but we’ve never seen a black preacher from America.’”

Jones was surprised too–by Liberians’ awareness of racial tension in the American South. “From the modern cities to the underdeveloped bush sections of the country, Africans plagued us with questions concerning Dr. Martin Luther King and the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama,” Jones later told InterVarsity Christian Fellowship students in the United States. “They quizzed us about the Emmett Till lynching in Mississippi and other racial disturbances.” According to Jones, these events, publicized by Radio Moscow and Radio Peking, were thwarting Christian missions.

On Jones’s journey back from Monrovia to Cleveland, Billy Graham waylaid him in New York City. Graham, fresh off several international trips himself, had just begun a massive evangelistic campaign in the metropolis and was dismayed that the crowds were all white. He asked Jones to help integrate the crusade.

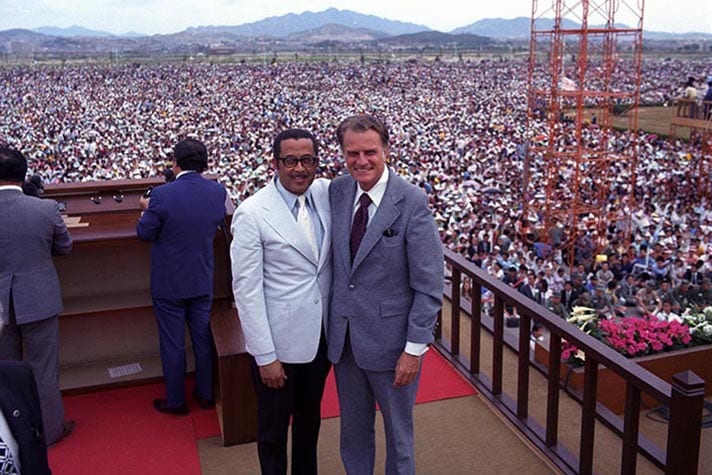

Jones soon engineered impressive black crowds of 8,000 and 10,000 in Harlem and Brooklyn. By August blacks comprised 20 percent of the attendance downtown at Madison Square Garden. When the crusade, which boasted an attendance of two million, finally closed after 68 days, it had become the longest crusade in Graham’s career. Jones said, “In New York, Billy once and for all made it clear that his ministry would not be a slave to the culture’s segregationist ways.” A month later, he joined the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) as a permanent associate. Over the next half dozen years, Jones led crusades that spanned the globe from Philadelphia to Nairobi. For several years, he lived in Monrovia, Liberia.

In the mid-1960s Jones returned to the United States as an even more full-throated proponent of civil rights. He, as Graham would begin to do, made his case to white America in international terms. At the 1966 World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin, sponsored by Christianity Today and the BGEA, Jones declared that racism was the “question on which the whole cause of evangelism will stand or fall in the non-white countries of the world.”

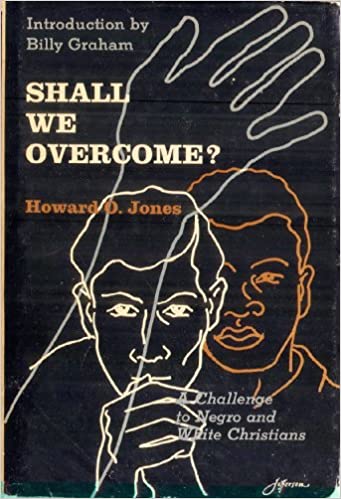

In his book Shall We Overcome, Jones invoked the legacies of James Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Bunche, W.E.B. DuBois, Medgar Evers, and other figures of the civil rights movement. Significantly, he also described his experiences in Africa. He recalled that Liberians had warmly welcomed him, wondering why they had never seen a black American missionary before. “I know,” wrote Jones, “that the problem of racism in America continues to hurt and hinder the work of Christian missions in Africa.” Melding global concerns and indigenous civil rights rhetoric—“Let us not be satisfied until we have overcome”—this globe-trotting black preacher powerfully challenged the white evangelical mainstream and shaped Billy Graham’s racial practices.

In his book Shall We Overcome, Jones invoked the legacies of James Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Bunche, W.E.B. DuBois, Medgar Evers, and other figures of the civil rights movement. Significantly, he also described his experiences in Africa. He recalled that Liberians had warmly welcomed him, wondering why they had never seen a black American missionary before. “I know,” wrote Jones, “that the problem of racism in America continues to hurt and hinder the work of Christian missions in Africa.” Melding global concerns and indigenous civil rights rhetoric—“Let us not be satisfied until we have overcome”—this globe-trotting black preacher powerfully challenged the white evangelical mainstream and shaped Billy Graham’s racial practices.