On March 14, an Asian American father brought his two young sons, ages two and six, on a mundane weekend errand: a Saturday trip to the store. But their visit to Sam’s Club in Midland, Texas, turned into a bloody nightmare when a nineteen-year-old man attacked the family, slashing the father and one of his sons across the face. According to the FBI, which has investigated the incident as a hate crime, the stabber had attempted to kill the family “because he thought the family was Chinese and infecting people with the coronavirus.”

The vicious attack prompted the FBI to raise the alarm about increased hate crimes targeting Asian Americans. “The FBI assesses hate crime incidents against Asian Americans likely will surge across the United States, due to the spread of coronavirus disease,” declared a report from the FBI’s Houston office. The FBI based this warning “on the assumption that a portion of the US public will associate Covid-19 with China and Asian American populations.”

The stabbing of this father and his young children is a particularly brutal instance of anti-Asian hatred, but it reflects a broader trend. At the same time that coronavirus cases are climbing, documented cases of anti-Asian harassment and hostility are also on the rise across the country. And just as Americans are uniting to fight the pandemic produced by a novel virus, they must come together to confront a more familiar enemy: racism.

In this battle, religious communities have a special role to play. As they have done in the past, they can support and stand in solidarity with Asian Americans. In addition, they can call Americans to conscience, leading the nation in addressing the deep-rooted problem of anti-Asian hatred, which has plagued our country well before the onset of the current crisis.

“I have never felt the need to shield my eyes until now, in New York, the city of my birth”

Acts of anti-Asian hate are real and rising. At the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center, a team of researchers led by Dr. Russell Jeung, Professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University, has been documenting and analyzing reports of anti-Asian hate incidents across the United States. (People who experience acts of hate can report the incident at this online form.) The data collected by the researchers present a clear trend of racial scapegoating. In one week alone, from March 19-26, the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center received notice of 673 hate incidents—nearly a hundred each day. These incidents affected Asian Americans of all ethnicities, with women three times more likely to report incidents than men, and they included harassment at everyday places—groceries, pharmacies, and big box stores. In addition, Asian American businesses have reported large decreases in business—approximately 18%—due to fears from customers about exposure to coronavirus in Asian-owned establishments and Asian-dominated ethnic enclaves.

Aware of the dangers and humiliations they risk by going about the simple business of daily life, Asian Americans are anxious. Efforts to venture outside the home are few and fraught, associated with the frightful possibility of physical attack, and for good reason. Beyond the stabbing at the Sam’s Club in Texas, there have been other acts of racist violence. At a subway station in New York City, a man beat an Asian woman with an umbrella and called her a “diseased b****.” And in California, high school students attacked an Asian American teenager accused of having coronavirus. The bullies’ blows were severe enough to send the teenager to the emergency room.

More commonly, there are smaller acts of hate that carry their own emotional and spiritual toll.

For example, there is the story of Father Ricky Manalo, a Filipino American Catholic priest in New York, who was enjoying a stroll when men leaned out of their truck to scream “Asian virus!” at him. The verbal assault forced the stunned priest to seek refuge in a nearby liquor store, and the incident made him warier of his environment, even though New York is his home. Later, on subsequent walks, he wore sunglasses and a scarf to mask his face and hide the fact that he is Asian American. “I have traveled all over the world,” he said, “yet I have never felt the need to shield my eyes until now, in New York, the city of my birth.”

And there is the story of the Korean American physician named David, who stopped for fuel and a cup of coffee at a gas station in a Martinsville, Indiana. The gas station refused to serve him.The business explained to the local police chief that “anyone of Chinese descent is not allowed in the store, and it was directly related to the spread of the coronavirus.” For his part, David found the experience unsettling. “I’ve never experienced anything like this before,” he told local reporters. “Part of me is hurt and angry and saddened that people can actually behave that way to another.”

And there is the story I heard last weekend—of how a friend in California was buying food for the week when another grocery shopper spit at her. As it turned out, the very day this incident happened, I was considering going out for the first time in two weeks. I needed to restock my pantry, and I longed to take a walk in the springtime sun. But after hearing my friend’s story, I wasn’t so sure about leaving the safety of home.

“Faithful Christian witness requires anti-racist work”

Alarmed by the resurgence of Yellow Peril discourses and the reports of harassment, discrimination, and violence, Asian Americans have responded creatively and forcefully.

Asian American politicians have warned against racist rhetoric and have urged their colleagues not to use the stigmatizing term “Chinese virus.” In the House of Representatives last week, Rep. Grace Meng introduced a resolution condemning anti-Asian racism in all its forms and urging law enforcement to document and investigate hate crimes against Asian Americans.

Asian American community groups have advocated for policies and programs to address xenophobia and racism and have worked to hold politicians accountable. In addition, they have worked on developing media campaigns and organizing support for individuals who have been targeted by acts of hatred.

Asian American journalists have called for responsible, fair, and accurate coverage of the coronavirus pandemic. They have urged their fellow journalists to avoid using terms that associate the virus with specific people or places and pairing coronavirus stories with generic images of Chinatown.

Asian American scholars have leaned into their role as educators and researchers. Dr. Jason Oliver Chang, Associate Professor of History and Asian American Studies at the University of Connecticut, created “Treating Yellow Peril,” a comprehensive set of resources to help students and teachers understand current coronavirus-related racism and the deeper history of anti-Asian sentiment in the United States.

And Asian American Christian leaders have drawn on their faith to address the moral crisis of anti-Asian hatred. On Tuesday, the Asian American Christian Collaborative released a statement that denounced both past and present anti-Asian racism and recommended a variety of measures to support Asian American people during this time of vulnerability. More than anything, the AACC urged all Americans, especially fellow Christians, “to speak without ambiguity against racism of every kind.” As the statement declared, “Faithful Christian witness requires anti-racist work, and silence only perpetuates the sins not addressed.” In less than two days, the statement received over 4,500 signatures, including from prominent faith leaders such as Rev. Dr. Walter Kim, President of the National Association of Evangelicals; Tom Lin, President and CEO of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA; Jim Wallis, Founder and President of Sojourners; Shirley Hoogstra, President of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities; and Jemar Tisby, President of The Witness, A Black Christian Collective.

Many people of faith across the theological spectrum have stepped up as allies and have expressed their support for Asian Americans. Unitarian Universalist ministers have dedicated time on Sundays to preaching about how the current pandemic has had a “disparate impact” on different communities, including Asian Americans, and have used their position of prominence to call for more “love in the time of coronavirus.” Justice-minded members of a Lutheran congregation in New Jersey have decried the hostility toward Asian Americans and denounced the sin of racism. And Muslim Americans, calling attention to the long-standing problem of orientalism, have also denounced anti-Asian prejudice.

Jewish Americans have been particularly vocal in their rejection of racism and their concern for Asian Americans. Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang co-authored an op-ed with Jonathan Greenblatt, President of the Anti-Defamation League, in which they described the long and overlapping histories of Sinophobia and antisemitism and urged “all Americans to come together and stand against the anti-Asian and anti-Jewish blame game.” And yesterday, representatives from over 180 Jewish American organizations issued a collective statement calling for “kindness and solidarity,” not scapegoating. The statement highlighted the importance of showing love, compassion, and empathy to neighbors, but also learning the lessons of Jewish history. Noting that “Jews as a people have a long history of being singled out and stigmatized during times of societal crisis, including being blamed without basis for the spread of disease,” the statement called “all people and particularly all leaders to reject conspiracy theories and the singling out of Asian Americans, foreigners, immigrants, Jews, or any other communities in this moment.”

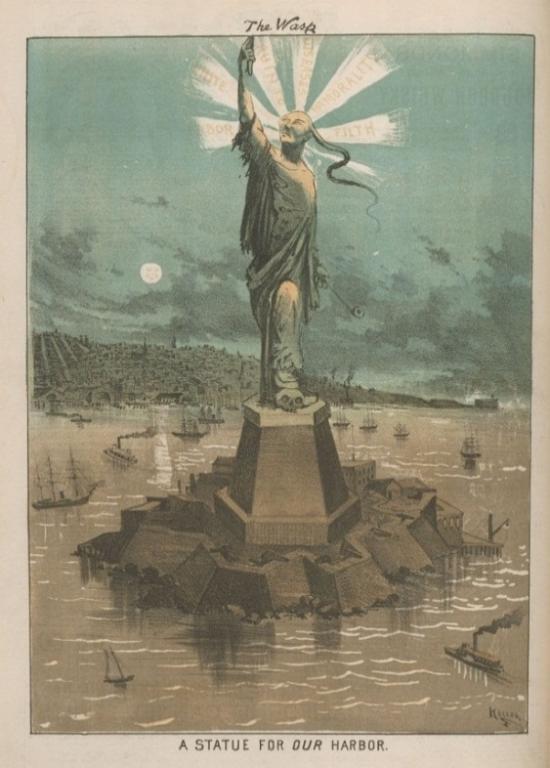

Learning from the past is important not only for Jewish Americans, but for all Americans. Asian people have long been demonized as threatening vectors of disease and vice. The history of the United States is filled with ugly episodes of anti-Asian racism, from the forced removal, lynching, and exclusion of Chinese migrants in the nineteenth century to the wartime scapegoating and incarceration of Japanese Americans in the twentieth.

But a look to the past also reveals how people of faith can play an important role in serving as allies and calling Americans to their better selves. Through words and actions, they can model what it means to stand on the side of justice and show love and compassion to neighbors, especially those who are vulnerable and suffering. They can offer moral leadership in a world marred by xenophobia and hate.

For example, Americans today might take inspiration from the courage of Rev. Emery Andrews, a Baptist minister who denounced the incarceration of Japanese Americans as “one of the blackest blots on American history; as the time that democracy came the nearest of being wrecked.” Christians who sympathized with Japanese Americans were only a small minority and were not able to prevent incarceration. However, as the historian Robert Shaffer argues, they nonetheless had an important impact—by offering “a spirit of community” to incarcerated Japanese Americans, by facilitating communication between people living within and beyond the camps, and supporting Japanese Americans in the fight against discriminatory laws during and after the war.

Or they might follow the example of the visionary student activists at the center of Stephanie Hinnershitz’ book, Race, Religion, and Civil Rights. She highlights how Filipino, Japanese, and Chinese American civil rights activists drew on their shared Christian values to organize coalitions and contest segregation and discrimination on the West Coast during the Second World War and the Cold War.

In both these historical cases, religion—along with relationships and personal experiences—animated a commitment to stand against racism. Amid the current pandemic, when the specter of death and disaster draws parallels to war, one wonders: will people of faith once again find the courage to take a stand against anti-Asian hatred again today? Some clearly have—but the rising number of hate incidents suggests we have more soul-searching, society-transforming work to do.

The wounds and scars of racism

The other day, I came across photographs of the family stabbed in Texas. The graphic images gave me chills. In one photo, a red, gaping wound reaches across one child’s face, from the eye to the ear. What struck me was not simply the brutality of the attacked that produced this wound, but the fact that the child is so very young–about the same age as my daughter was when she heard her first racist epithet hurled at our family. That verbal attack was short and quick, just a couple words yelled by driver in a car passing us on Second Avenue in Manhattan. We reacted just as the Catholic priest from Brooklyn did—stunned at first, aghast that such words would be uttered in one of the most multicultural cities in the world. My daughter and I were fortunate, and we walked away from the incident with our bodies fully intact. But our hearts were a little broken that day. Since then, it has been harder for both of us to move through the world with the same degree of love and joy and trust.

Racism and acts of xenophobic hate can wound deeply and leave indelible scars—physically, emotionally, and spiritually—on individuals and on our entire society. But I also believe that most cherished values held by religious communities—love, justice, compassion—can offer a way for individuals and societies to heal and also prevent injury in the first place.

During this pandemic, which brings into stark relief the interdependence of our lives, may we all remember that the suffering that afflicts some of us—whether Covid-19 or racism—ultimately shapes the wellbeing and the survival of all of us.