Many Old Testament passages have posed difficulties to readers through the centuries. I am presently wrestling with an epic dilemma. If I am reading a particular text right, then God deliberately and knowingly gave his people bad laws and statutes, to lead them on the wrong path. Can this possibly be the case?

The idea that the Old Testament contains troublesome and troubling texts is nothing new. We look at the passages commanding extermination and genocide that I discussed in my 2011 book Laying Down the Sword. God’s command that Abraham sacrifice Isaac is another of what Phyllis Trible called “texts of terror,” which have agonized Jewish, Christian and Muslim thinkers alike. Muslims believe that the Abrahamic command applied to Ishmael rather than Isaac, but the basic problem remains.

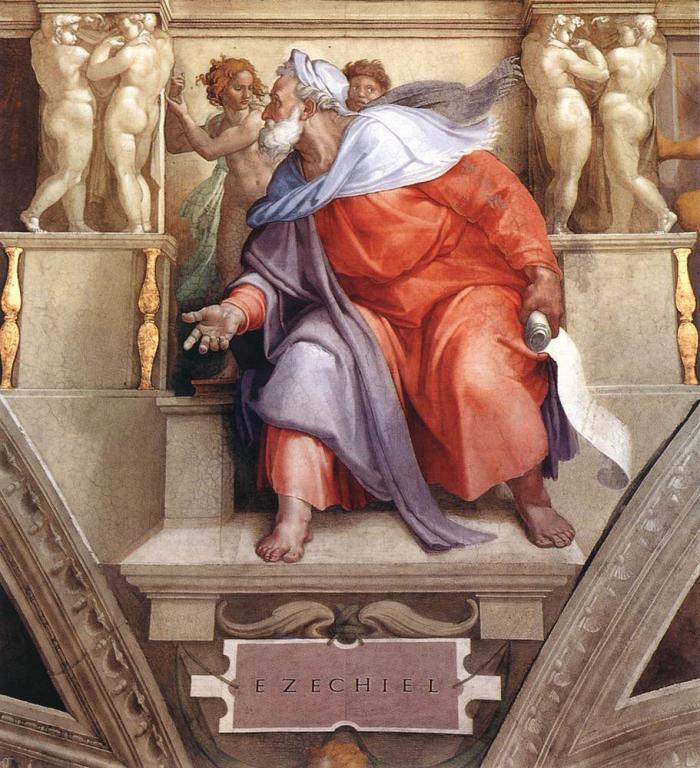

Ezekiel’s Denunciation

But here is another text that is, well, challenging. It comes from Ezekiel, who in the early sixth century BC was denouncing the children of Israel in the ferocious manner that we particularly associate with Old Testament prophecy.

Ezekiel complains that the Israelites have systematically betrayed and disobeyed God, who has given them endless chances to repent, and yet they carry on doing the same dreadful acts, pursuing the same idolatry. Much of the text concerns the practice of worshiping pagan deities on the high places, making drink offerings, but also “the sacrifice of your children in the fire” (Ezekiel 20.31). And then in the middle of this, we have this passage, from Ezekiel 20.25-26 (NIV):

So I gave them other statutes that were not good and laws through which they could not live; I defiled them through their gifts—the sacrifice of every firstborn—that I might fill them with horror so they would know that I am the Lord.’

The King James version has

Wherefore I gave them also statutes that were not good, and judgments whereby they should not live; And I polluted them in their own gifts, in that they caused to pass through the fire all that openeth the womb, that I might make them desolate, to the end that they might know that I am the Lord.

As I read this, I would paraphrase the text as follows, and I hope this is a fair interpretation:

The people of Israel have gone far astray. In response to that, I, God, have deliberately given them laws and commands that were so bad that they were intolerable. That included orders to sacrifice their own children. These laws were deliberately intended to be so atrocious that as the people grieved, they would realize just how far out of line they were, and would return to true faith.

This reading faces the problem that the logical sequence of the original text is anything but clear, specifically in the linkage between the first and second sentences. God gave bad commands; they sacrificed their children. But are we meant to read that God’s bad commands directly involved child sacrifice, or led to such acts? We can debate this, but I think that is a natural reading.

Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel

The evidence for human sacrifice in the ancient Hebrew world is abundant and well-known, although in the Bible as we have it older tales have been edited to make them more acceptable. The story of Jephthah’s daughter in Judges 11 looks like an instance. When sacrifice is described, it is condemned in the most forthright manner, as in the stories of kings Ahaz (2 Kings 16) and Manasseh (2 Kings 21). Isaiah denounces those who “sacrifice your children in the ravines and under the overhanging crags” (Isaiah 57 NIV). That is over and above several references to human sacrifice in neighboring nations, like the Moabites and Gibeonites.

A common assumption among modern scholars is that human sacrifice was indeed practiced in the Hebrew world. It was quite widespread at particular times and places, and many people in those eras believed that this was based on divine commandments. In the seventh century, the radical reforming king Josiah included the practice as one of his targets:

He desecrated Topheth, which was in the Valley of Ben Hinnom, so no one could use it to sacrifice their son or daughter in the fire to Molek (2 Kings 23.10)

Soon afterwards, prophets like Ezekiel and Jeremiah proclaimed forcefully how utterly wrong the Israelites had been, and declared that the authentic tradition – as they understood it – neither permitted nor legitimized any such practices. However common it had once been, child sacrifice was eliminated during the sixth century. When we read the major prophets , we need to be aware of that struggle against the practice as one of the dominant themes in religious/political debates of that era, roughly the years 650-550 BC. That hostility to child sacrifice then became a major feature of the Deuteronomistic literature. The classic study of this process is Jon Levenson’s The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity (Yale 1993).

Through the years, quite a few writers have tried to say that “passed through the fire” meant a kind of symbolic initiation in which a child was held near fire, or between two fires, but suffered no real harm. There are societies around the world that do something like this to their offspring, and some Australian Aborigines practice a kind of “smoking” ritual for babies. But a heavy preponderance of Biblical scholarship and archaeology agrees that such a non-lethal “fire baptism” is simply not what we find in the Canaanite / Phoenician / Hebrew world. In the Old Testament context, it is abundantly clear that we are talking about real sacrifice and actual, literal, death. For one thing, you would not be “desolate” or “filled with horror” if your child had just been subjected to such a token exposure to smoke.

Purged Scriptures and Satanic Verses

Assuming that my reading of the Ezekiel text is right, it is not clear what these “statutes and judgments” were. The words used most naturally refer to texts within the Bible itself, although as we have it, the text does not include anything that would fit the description of a command or license to sacrifice. The idea of dedication or consecration is certainly there, for example at Exodus 13.1:

The Lord said to Moses, “Consecrate to me every firstborn male. The first offspring of every womb among the Israelites belongs to me, whether human or animal.”

At Exodus 22.29, God commands

Do not hold back offerings from your granaries or your vats. You must give me the firstborn of your sons.

But giving or dedication need not imply sacrifice. Leviticus and Deuteronomy both include specific prohibitions of the practice. Having said that, those prohibitions would not have been needed if people were not actually carrying out such actions, and needed to be stopped. Jeremiah 7.31 has God declare that

They have built the high places of Topheth in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to burn their sons and daughters in the fire – something I did not command, nor did it enter my mind.

That second part of the sentence is odd unless some people at the time actually believed that this is exactly what God had commanded, forcing Jeremiah to set them right. Was that belief based on some text that people believed to carry scriptural weight?

Might Ezekiel and Jeremiah even be denouncing the passages in Exodus, as they were popularly accepted and executed? Were those the bad statutes and judgments? It’s a radical thought.

Let me offer another interpretation that fits the evidence as we have it, although it is certainly not the only possible explanation. Hypothetically, let’s suppose that there once circulated stories or texts that were read, with whatever justification, as legitimizing or commanding child sacrifice. During the time of Ezekiel and Jeremiah, those supposed texts were forcefully condemned, and they have simply vanished from view. The Hebrew Old Testament canon was not defined until the fourth century BC at the very earliest, and there was still considerable latitude and debate for several centuries after that point. Prior to the fourth century BC, it is far from clear that the notion of a canon even existed, and the frontiers separating scriptures and non-scriptures were highly fluid.

It is perfectly possible that in Ezekiel’s time, around 600 BC, at least some people in Israel venerated particular texts and regarded them as authoritative or inspired, even attributing words to God himself, although these writings have now been lost irretrievably. Might these have been the “statutes and judgments” in question?

Throughout the Old Testament itself, we find passing references to perhaps twenty texts that once existed, but which have vanished from history. Such for instance were the Book of Jasher, Sefer HaYashar; or the Book of the Wars of the Lord; or the Book of Shemaiah the Prophet, all cited in the canonical Old Testament as we have it today. At some point, somebody decided that Amos and Micah were canonical prophets and Shemaiah was not, but the process and timing of that decision are quite obscure.

We also know that some particular stories once existed in a form other than we presently have them, and that at some point, they were edited or adapted to accord with later sensibilities. The obvious example is the direct personal encounters that individuals had with God, which in later readings were transformed into meetings with angels. Such for instance was Jacob’s wrestling with the mysterious individual at Peniel (Genesis 32, compare Hosea 12.4); and probably the meeting of Samson’s parents with a heavenly figure in Judges 13. And as I suggested, that would also apply to stories like that of Jephthah’s daughter. Again hypothetically, perhaps some older stories were so irreconcilable with emerging orthodoxies that they were not even adapted or censored, but simply abandoned. We can’t begin to imagine what they might have said.

Rabbinic Readings

As you might expect, there are plenty of rival interpretations of the Ezekiel text by Christians and Jews alike. Some of the ugliest readings through the centuries have used the passage to justify anti-Judaism, and to point out the supposed horrors of the Mosaic Law. As Hyam Maccoby remarks, anti-Semites have long used the passage to argue that the Hebrews practiced systematic human sacrifice, and did so explicitly as part of the religious system.

The Ezekiel text caused some agony to rabbinic scholars. Maccoby collects some of the more important discussions, which produced discussions of varying degrees of plausibility and helpfulness. One interesting solution assumes that parts of the text should be read not as God’s own words, but quotations of what the rebellious Israelites were saying to God, for example:

[for they said that] I had even given them statutes that were not good and judgments by which they could not live,

That is from the nineteenth century rabbi Meir Loeb Malbim. It makes considerable sense, although it does rewrite the text without too much justification. The result says what we would like it to say. Even so, the idea that we should read that verse in a sarcastic way is attractive (“In their arrogance and foolishness, they even said that…”).

That is anything but the only interpretation of the text. For one thing, Ezekiel’s explosive theme of divine deception and false revelation actually does occur elsewhere in the Bible. Not long ago, I posted at this blog about the strange story of the righteous prophet Micaiah, cited in 1 Kings 22, who deliberately and consciously gave a false prophecy, apparently through God’s command, in order to destroy a sinful king.

Even so, I am still wrestling with the Ezekiel passage in which, at first sight, God declares that “I gave them other statutes that were not good, and laws through which they could not live.”

My, but that would be an interesting text to preach on. You go first.

Some Sources

Besides Levenson’s classic book, there are plenty of solid scholarly works on the whole human sacrifice theme. See for instance:

Daphna Arbel, Paul C. Burns, J. R. C. Cousland, Richard Menkis, and Dietmar Neufeld, eds., Not Sparing the Child: Human Sacrifice in the Ancient World and Beyond (Bloomsbury, 2015)

Heath D. Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel (Eisenbrauns, 2017).

Stewart James Felker has a provocative discussion of the various texts, on “The Legacy of Child Sacrifice in Early Judaism and Christianity“. This appears at one of the Patheos sites devoted to combating religion. See also Felker’s lengthy follow-up posts, “Does God Admit that He Legally Sanctioned Child Sacrifice in the Book of Ezekiel?” and “God and Child Sacrifice (Ezekiel 20:25-26): The Last Pieces of the Puzzle.” Felker’s three posts together run to some twenty thousand words. He is good on the different ways various translators have tried to cope with the thorny text.

Scott Walker Hahn and John Sietze Bergsma, “What Laws Were “Not Good”? A Canonical Approach to the Theological Problem of Ezekiel 20:25-26,” Journal of Biblical Literature 123(2) (2004), 201-218.

Karin Finsterbusch, Armin Lange, and K.F. Diethard Römheld, eds., Human Sacrifice in Jewish and Christian Tradition (Brill, 2007).

Francesca Stavrakopoulou, King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities (Walter de Gruyter, 2004).

Moshe Greenberg wrote the splendid volume on Ezekiel 1-20 in the Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries (1983).

I add a confession. I had neglected to include a truly important piece on this whole topic, namely Baruch Halpern, “The False Torah of Jeremiah 8 in the Context of Seventh Century BCE Pseudepigraphy: The First Documented Rejection of Tradition,” in S. White-Crawford, Amnon Ben-Tor, W. G. Dever, A. Mazar and J. Aviram, eds., Up To The Gates Of Ekron: Essays on the Archeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymur Gitin (Israel Exploration Society, 2007), 337-343. My thanks to Dr. Halpern for the gentle reminder!