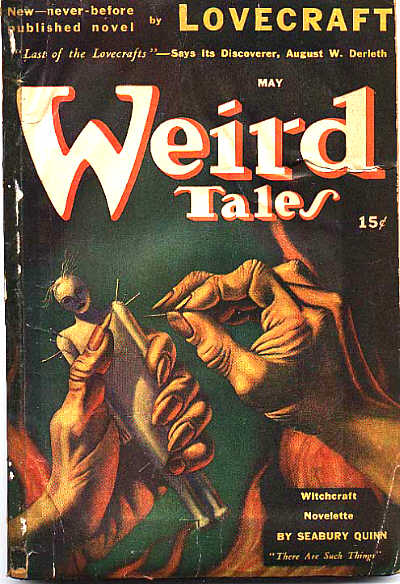

The HBO series Lovecraft Country is reviving interest in the author H. P. Lovecraft, in whom I have a deep proprietorial interest. He and I go back a long way. When I first discovered him back in 1968, I assumed I was the only person in the world who had heard of him. Later, I found there were plenty of others making the same assumption, until he finally entered a cultural mainstream. He is even in Penguin Modern Classics. This blogpost suggests why you should read him, even if you have no interest in horror fiction

Much of the recent writing about Lovecraft (1890-1937) points out, indisputably, that he wrote a great many offensive and really nasty remarks about other races, including Italians, Syrians, and other white ethnic groups, as well as Blacks and Jews. The one possible defense I would make is that he was educable. Initially very anti-Semitic, he reached the point in his later years where most of his social circle was Jewish, with authors like Robert Bloch, and he had lots of nice things to say about them and about Jews generally. In 1924, he married a Jew, Sonia Greene. Maybe, had he spent more social time with those other groups, that familiarity would had a similar effect, but who knows?

I sometimes quote Lovecraft’s views to illustrate the concept of whiteness being a flexible and socially constructed thing. In 1920, say, Italians and Slavs certainly were not white for an old stock American world view like his. Only gradually did the label extend that far, with the Second World War as a key point of transition.

Lovecraft is best known as a horror author, who achieves absolutely his greatest effects by what he does not say – everything is left to veiled hints. He is superb at what he does. But let us assume that you care nothing for horror, and you are the sort of Anxious Bench reader interested in history and religion. Well, have I got an author you will love.

Lovecraft grew up in Providence, in the vicinity of Brown University, and he had a deep antiquarian passion for college and city. In his writings, Providence became Arkham, Brown became Miskatonic, and many historic New England communities entered his mythology, usually as the scene of dark and sinister supernatural misdeeds. Wikipedia actually has a map of these locales, this original “Lovecraft Country.” You can have a wonderful time touring those historic sites, within Providence and around New England, and delve into the region’s Lovecraftian history at Marblehead, Gloucester, Salem, and the rest. (Newburyport is Innsmouth). In Providence proper, see for instance the College Hill walking tour,

Lovecraft affected to care for nothing that had happened in America after about 1790, but prior to that date, he was a highly skilled expert – a fine antiquarian, if not a historian in any modern sense. He must have spent a large portion of his youth in archives and historical society collections. The Providence he loved so well was basically that of 1765, with the intimate details of every street and alley.

Lovecraft had read very widely indeed in that history, and in his stories, he often creates fictional letters and documents that precisely catch the flavor of colonial era language and style. If you are interested in the history of the years between the Great Awakening and the Revolution, you will be stunned at the impeccable skill with which he does that. Just as an example, his story The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (written 1927) imagines a group of ancient and truly evil wizards and necromancers, who have greatly extended their lives after their original experiments in Salem: they were key members of the rumored coven there. At one point, a letter between two of these villains is discovered, in which they discuss loathsome occult secrets. But the rabidly evil sorcerer Joseph Curwen ends with some chatty proto-Tripadvisor hints and travel directions:

I rejoice you are again at Salem, and hope I may see you not longe hence. I have a goode Stallion, and am think’g of get’g a Coach, there be’g one (Mr. Merritt’s) in Prouidece already, tho’ ye Roades are bad. If you are dispos’d to Travel, doe not pass me bye. From Boston take ye Post Rd. thro’ Dedham, Wrentham, and Attleborough, goode Taverns be’g at all these Townes. Stop at Mr. Bolcom’s in Wrentham, where ye Beddes are finer than Mr. Hatch’s, but eate at ye other House for their Cooke is better. Turne into Prou. by Patucket ffalls, and ye Rd. past Mr. Sayles’s Tavern. My House opp. Mr. Epenetus Olney’s Tavern off ye Towne Street, Ist on ye N. side of Olney’s Court. Distance from Boston Stone abt. XLIV Miles.

If you have ever delved into correspondence of that era, in Britain or the American colonies, you will immediately recognize this as pitch-perfect in tone and detail, and even punctuation. The wizardly advice about finding the best meals is wonderful. (SPOILER: Lovecraft was often pretty funny, with lots of in-jokes, though mighty Cthulhu forbid he should ever let on to his readers).

Lovecraft had a deep interest in colonial churches, even if that meant using them as the setting for ghastly supernatural atrocities. I have to offer one nugget, related to Curwen’s quest for a wife. He finds a young woman named Eliza Tillinghast, whom in 1763 he married in Providence’s Baptist Church. As I wrote that sentence, I wanted to amend it to “First Baptist,” a splendid structure in the city, but as Lovecraft knew perfectly well, the present building dates only from 1775. He wasn’t wrong about such things.

Curwen and Eliza face religious strains, as she was a Baptist, and his own tradition was notionally Congregationalist. In fact, as I say, his spiritual views were from somewhere beyond the tenth circle of Hell. As Curwen’s modern day descendant Charles Dexter Ward explores the genealogy, he finds a birth record in Providence:

On the seventh of May, 1765, Curwen’s only child Ann was born; and was christened by the Rev. John Graves of King’s Church, of which both husband and wife had become communicants shortly after their marriage, in order to compromise between their respective Congregational and Baptist affiliations. … Ward had tried this source because he knew that his great-great-grandmother Ann Tillinghast Potter had been an Episcopalian.

John Graves was a historical figure, long the Anglican minister of King’s, until his Toryism forced his flight during the Revolution. King’s Church had a fascinating history, as it evolved into the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John and the seat of the diocese, until it closed in 2012. It has since become “an exhibition and reconciliation center focusing on the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” an imaginative use of the space.

Or let me tell Lovecraft’s original story another way. Joseph Curwen and his wife had religious differences, between a faithful Baptist and a monstrously evil Satanic necromancer. I’m sure you understand how tense those mixed marriages can be. So they split the difference and end up … in the Episcopal Church. That’s the half way point.

Sounds about right.