I couldn’t tell you how many times I had walked past her. Dozens for sure. Maybe hundreds. Located in the oldest part of Baylor University campus, on the wall of a brick pavillion right between Old Main (built in 1887) and Burleson (originally built as the women’s residence hall in 1888), there is an engraved stone tablet memorializing one of Baylor’s early female professors.

I couldn’t tell you how many times I had walked past her. Dozens for sure. Maybe hundreds. Located in the oldest part of Baylor University campus, on the wall of a brick pavillion right between Old Main (built in 1887) and Burleson (originally built as the women’s residence hall in 1888), there is an engraved stone tablet memorializing one of Baylor’s early female professors.

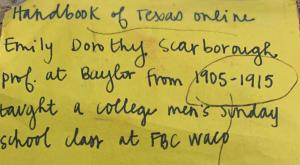

But it wasn’t until a student prompted me that I finally noticed her. “Dr. Barr,” the student said, “I think you will like Dorothy Scarborough.” Then she handed me a note, taken from her afternoon research in the Texas Collection. I taped it on my computer monitor so that I wouldn’t lose it. This is what it said: “Emily Dorothy Scarborough prof. at Baylor from 1905-1915 taught a college men’s Sunday School class at FBC Waco.” The note stayed stuck on my monitor for quite a long time. So long, that the name stuck in my head too. And then, one day, as I walked through that brick pavillion, I looked up and saw her. Dorothy Scarborough. Baylor graduate, faculty member at both Baylor and Columbia, folklorist and novelist. Right where  she had always been, in the Folmar Pavillion facing Founder’s Mall.

she had always been, in the Folmar Pavillion facing Founder’s Mall.

There is so much I could tell you about Dorothy Scarborough. I could tell you how she was Texas born and bred, living for several years in West Texas not far from where my father grew up. I could tell you how her family home in Waco was 1717 Speight Avenue–now the site of the women’s dormitory Memorial Hall on Baylor campus (that the Baptist women at my current church raised money to help fund during the 1930s and that my sister once lived in during the 1990s). I could tell you how she was one of the early women graduates from Baylor as well as one of Baylor’s first female professors. (Did you know that Baylor was one of the first coeducational universities, second in the nation after Oberlin College?)

I could tell you how relentlessly Dorothy Scarborough pursued her PhD in literature–spending summers in graduate school at the University of Chicago, one year in residence at Oxford University, and finally earning her PhD from Columbia University in 1917. I could tell you about her superb skills as a teacher and researcher. Columbia immediately hired her as faculty after she completed her doctorate, and her dissertation was so “widely acclaimed by her peers” that it became “a basic reference in the field”. Baylor  later recognized the scholarship of Scarborough, awarding her an honorary doctorate in 1923 after the publication of her first novel. Or I could tell you how Scarborough, a single woman, taught a “popular and influential” Sunday School class at First Baptist Church in Waco–the college-men’s class! I could even tell you how bad her handwriting was (although I was secretly pleased to see a fellow scholar with handwriting almost as bad as mine…).

later recognized the scholarship of Scarborough, awarding her an honorary doctorate in 1923 after the publication of her first novel. Or I could tell you how Scarborough, a single woman, taught a “popular and influential” Sunday School class at First Baptist Church in Waco–the college-men’s class! I could even tell you how bad her handwriting was (although I was secretly pleased to see a fellow scholar with handwriting almost as bad as mine…).

But this is Halloween. So why don’t I tell you about Dorothy Scarborough’s most popular ghost story.

Scarborough always liked a good ghost story. Afterall, she wrote her acclaimed dissertation (published immediately after defense) on The Supernatural in Modern English Fiction. “The night of the soul attracts us all,” she wrote. “The spirit feeds on mystery. It lives not by fact alone but by the unknowable, and there is no highest mystery without the supernatural.” She also edited two volumes of ghost stories that you can still find in print and digital format–Humorous Ghost Stories and Famous Ghost Stories, and wrote the introduction to The Best Psychic Stories. Because she wrote that “Ghosts are the true immortals, and the dead grow more alive all the time,” she would probably be gratified that her stories about ghosts continue to live long after her own death.

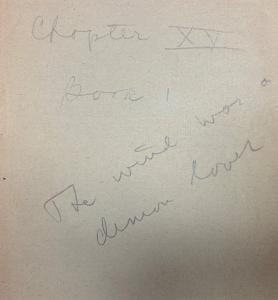

Her most famous ghost story also continues to live. It was first published in 1925. In a publicity stunt, that didn’t turn out especially well, it was published anonymously and only later revealed to be her work. Although you probably won’t find the first line of this novel on any lists for ‘famous first line of books’, I think it belongs there.

“The wind was the cause of it all. The sand, too, had a share in it, and human beings were involved, but the wind was the primal force, and but for it the whole series of events would not have happened. It took place in West Texas, years and years ago, before the great ranges had begun to be cut up into farms and ploughed and planted to crops, when there was nothing to break the sweep of the wind across the treeless prairies, when the sand blew in blinding fury across the plains, or lay in mocking waves that never broke on any howsoever-distant beach, or piled in mounds that fickle gusts removed almost as soon as they were erected–when for endless miles there seemed nothing but wind and sand and empty, far off sky.” (1)

This was the opening paragraph for Scarborough’s novel The Wind. The ghost in the story is the primeval force of the wind itself, or as Scarborough calls it,”a demon lover.” The relentless, invisible force of the West Texas weather drives Letty, the main character, into severe anxiety, despair, madness, and finally to her own death. “Hell was a place where the winds blew all the time, winds that tormented you, but would not let you you die,” thought Letty towards the end of the novel (275). “Winds that drove you almost crazy, but didn’t let you know the relief that complete insanity would bring. . . . Demon winds! . . .” The story proved gripping enough to immediately attract the attention of famous actress Lillian Gish. She convinced MGM studios to turn it into a movie released in 1928. Rotten Tomatoes applauds the film as “one of the few silents to stand the test of time” as well as “one of Lillian Gish’s greatest achievements in a powerfully dramatic silent film.” Indeed, one of the best scenes in the movie shows Gish, wild-eyed with fear, watching as the wind mercilessly strips away the sand hiding the evidence of her crime–the buried corpse of the man she had murdered.

Scarborough’s writings show that she was fascinated not only with ghosts, but also with the manifestation of the supernatural through primeval forces like the wind. But the wind, I think for Scarborough, represented more than just a force of nature. Listen to how she describes it taking Letty in the end (sorry for the spoiler!)

“Why struggle against a force that was a devil, and all-powerful? She had known all along that the wind would get her!…No use to fight any more! She would give up. The wind had risen almost to cyclonic fury now. Again the curtains of sand were rolled up from the plains to the sky, wavering, shifting, their gigantic folds writhing with hideous suggestion. What horrors did those curtains hide? With a laugh that strangled on a scream, the woman sped to the door, flung it open and rushed out. She fled across the prairies like a leaf blown in a gale, borne along in the force of the wind that was at last to have its way with her.” (337)

Anyone else hear the overtones of sexual violence? Rape, even? Letty was a young woman left adrift after the death of her mother. She left her beloved Virginia to live with an unknown relative in Texas, because she had no other choices. She had no livelihood and no money. “I didn’t know what else to do,” she explains to a stranger on the train as she traveled to her new home. “Oh, why aren’t girls taught to make their living and take care of themselves, the same as men?” (22) Her lack of choices drove her to marry a man she didn’t love for the protection he could offer (patriarchal bargain, anyone?). At the climax of the book, we find her huddled in her house, hiding from the wind and trying to figure out what she could have done differently. Even with the power of hindsight she can’t see a different future for herself. “Life had got her in a corner and had driven her to do things she hadn’t wanted to, and that didn’t rightly represent her. Life, in that last year, had been like a norther that battered her and scared her almost to death, so she couldn’t know what to do. She had just tried to struggle on the best she could, through one hour to the next. . .” (290) Finally, when she had lost all her agency, beaten down by the mercilessness of her circumstances, she surrendered to the primeval force that she had never been able to escape. I find it really interesting that Scarborough emphasizes that the deciding factor in Letty moving west, and hence the decision that led to her becoming a victim of the demon wind, was her Virginia pastor. “The pastor fixed it up for me!” she proclaimed hysterically. “He thought it would be the best thing I could do. He said he had prayed over it!” (266)

Umm, anyone want to guess what the wind might have represented?

Let me give you two hints.

- Dorothy Scarborough knew all to well the difficulties of being a woman in a man’s world. She struggled for many years to earn her PhD and faced what must have been a bitter disappointment at Oxford University. She learned when she arrived in 1910 that Oxford was not yet granting degrees to women. As Patricia Wallace records, Scarborough was dismayed “that this celebrated university did not at that time deem women worthy of receiving a degree!” So she returned to Waco in 1911 to continue teaching at Baylor and attending summer classes at the University of Chicago. It would take her another 6 years to earn her doctorate finally at Columbia. Her experience at Oxford led to the publication of a serial novel in 1925 aptly named The Unfair Sex. The main character, Ginger, channels Scarborough’s outrage that “Oxford, the seat of intellectual development for the Anglo-Saxon world, was actually behind Texas when it came to giving women a chance for education.” Scarborough also found that, when The Wind was published, at least one reviewer assumed the author had to be a man. “Here is a powerful novel whose author is anonymous,” wrote a reviewer for The News in St. Joseph, Missouri. “It is a piece of American realism which is as searching, and relentless as its name. One wonders why so fine a piece of work is hidden under the veil of anonymity. One thing is certain, a man wrote it. No woman ever dealt so cleverly of the upper surface of a woman’s mind and left the deeper ones untouched. Also it needed a man to handle the terrific tragedy so convincingly. A woman would shrink from its realistic horrors.” (Dorothy Scarborough Papers #153, Series II, Box 2, Folder 1, The Texas Collection, Baylor University) The Wind did very well when it was anonymous, but the sales decreased significantly when Dorothy Scarborough’s name became known–could it have been because she was a woman?

- Dorothy Scarborough wanted The Wind to show how the masculine narrative of conquering the West, as cowboys and ranchers, looked different when seen through the eyes of a woman. Listen to what she writes in response to a negative review of The Wind: “I was trying to show the woman’s side of pioneer life, because most of the western fiction had been about men and their struggles.” (Dorothy Scarborough Papers #153, Series II, Box 2, Folder 1) Surely, she also wrote, because Letty was a young girl, “she would naturally take a different view of many things from that held by the cowboys.” Scarborough, a woman born long before the 19th Amendment gave us the right to vote and even before most women had the opportunity for a college education (much less advanced degrees), understood that women experienced life differently from men. While the cowboys were out riding with each other, herding cattle along the trails, the women were left alone on the homestead. As she wrote in her notes for the novel, “A westerner thinks of wind differently. It is life-giving. How should we have any water in our windmills if there was no wind? We should die, and our cattle should die. But the women never get used to it, of course.” (Dorothy Scarborough Papers #153, Series II, Box 2, Folder 2) Scarborough captures the vulnerability of these women–showing in one chapter how Letty is caught off guard, in her bed sleeping, when a cowboy comes stalking into her home uninvited and unwelcome. Some women, like Letty’s neighbor Cora, could make the patriarchal bargain of their Wild West marriages successful–carving out a relatively stable and happy life. Yet other women, like Letty, would find the burden of patriarchy too heavy a load to carry. It is telling that the song Letty sings shortly before choosing a loveless marriage is about her fear of the strong forces in her life. “Lord, I don’t want to die in a storm, in a storm! Lord, I don’t want to die in a storm, in a storm! When the wind blows east, and the wind blows west, Lord, I don’t want to die in a storm!” (156 and 173)

Could Scarborough’s wind be the relentless force of a masculine-centered society on the life of a vulnerable woman? Could the unrelenting winds that screamed at her and tore at her body, beating her down until she lost the will to live, have been her lack of choices? Letty’s inability to escape a life and a marriage she never wanted? Could Dorothy Scarborough, a well-educated single woman with her own vocation, be haunted by the what-ifs of her own life? What if she hadn’t achieved her education and job? What if she had never been taught to make her own decisions? Was she haunted by the fate of other women in her world–women with fewer choices than she had?

Of course, maybe I am reading too much into the story. Maybe The Wind is no more than what it appears: a good ghost story spun by a talented writer. A classic European Gothic horror novel with a West Texas twist. Then again, as she prepared to write The Wind, Dorothy Scarborough reminded herself to “read Hardy’s Tess, to get the effect of a girl driven to desperation by forces outside that are too strong for her….” (Dorothy Scarborough Papers #153, Series II, Box 2, Folder 2).

Just something to think about. Happy Halloween, y’all!

For more about Dorothy Scarborough: See Jean Fair’s Baylor MA Thesis, “I Only Love Them:” Dorothy Scarborough and the Supernatural in Literature; Patricia Wallace, A Spirit so Rare: A History of the Women of Waco (1984); and the Dorothy Scarborough Papers housed in the Texas Collection at Baylor University. All quotations from The Wind were taken from the 1979 edition by the University of Texas.