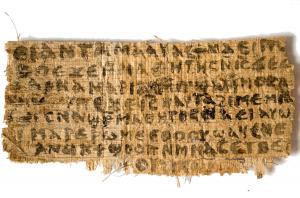

In 2012, Harvard Divinity School professor Karen King made international news with a “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.” She had translated a scrap of papyrus whose Coptic text included a statement by Jesus which began with the words, “My wife.”

King noted that the fragment in no way proved that the historical Jesus had a wife. However, she used the fragment to assert that relatively early communities of Christians – say, late-second century – believed that he had married. This pointed to an alternative history, one without Christianity’s developing suspicions about female sexuality and its valorization of celibacy.

King noted that the fragment in no way proved that the historical Jesus had a wife. However, she used the fragment to assert that relatively early communities of Christians – say, late-second century – believed that he had married. This pointed to an alternative history, one without Christianity’s developing suspicions about female sexuality and its valorization of celibacy.

Almost from the start, other scholars expressed doubts about the fragment’s authenticity, pointing to everything from grammatical errors to odd word choices to penmanship to the fragment’s straight rather than ragged edges.

Rather than slowing down, King doubled down. She published her translation of the fragment and a defense of its authenticity in the Harvard Theological Review.

Enter Ariel Sabar. A journalist, Sabar had followed this story from the beginning. By 2016, he had pieced together the winding tale of a not-very-artful forgery that had duped a famous professor. The forger was Walter Fritz, a German expat living in Florida. A former and mostly failed student of Coptic, Fritz had dabbled in various businesses. His greatest “success” came through a pornography website on which he featured videos of his wife with other men. In 2016, Sabar published his findings in The Atlantic. Confronted with overwhelming evidence, King conceded that the Gospel of Jesus’s wife was a likely forgery.

Sabar has now turned his exhaustive research into a gripping book, Veritas. In it, he portrays Karen King as an almost willing participant in a hoax. She set aside her initial suspicions, relied on her friends’ assessment of the papyrus, and ignored radiocarbon dating that estimated a much later date for the fragment. It’s almost as if she wanted to be duped.

Why? For starters, the fragment accorded with her own understanding of a diverse array of early Christian communities, a world in which noncanonical texts are as significant as those of the New Testament. A world in which women exercise leadership and in which theological boundaries remain fluid. As Sabar comments, she evidenced a “disdain for the straitjacket of creed and canon,” because they constrained human beings, especially women. Throughout her career, King cast doubt on the reliability of canonical texts – through her participation in the Jesus Seminar – and translated and analyzed texts such as the Gospel of Judas and the Gospel of Mary Magdalene. As King rightly pointed out, many ideas about early Christianity had been built not on scholarship or facts, but on faith. So we needed more facts. New facts.

In Sabar’s telling, though, King replaced one faith-based history she didn’t like with a new faith-based history partly of her own imagination. If she wanted a fourth-century text to become a second-century text, it became a probable second-century text. After all, in keeping with postmodern theory, facts were illusory. “History,” King wrote in What is Gnosticism?, “is not about truth but about power relations.” With that recognition, she wrote elsewhere, “one need never say no to a story, a song, a poem that gives life, heartens, teaches, or consoles, and need never fail to call it true.” King accordingly could not “say no” to Walter Fritz and his fragment. It was the truth she wanted. The facts of the case were inconvenient.

Sabar’s summary is sharp: “Either the best kind of faith belonged to the people with the most accurate data, the fact finders for whom the universe’s mysteries were less fuel for the contemplation of God than a complex problem that science would eventually solve. Or the best facts were no different from faith, a set of collectively agreed-upon illusions with no more basis in the observable world than belief in an unseen God. If fact and faith were the same, that is, then either faith didn’t exist, or facts didn’t. Not in the way most people thought, anyway. But King wanted it both ways: she sought to expose the Church’s ‘facts’ as positions while promoting her own positions as facts.”

Veritas is a damning account. Undoubtedly, King should have investigated the fragment’s provenance. She should have sought the advice of a wide array of Coptic scholars. She should have heeded all of the flashing-red-light warning signs. She shouldn’t have called her text a “gospel.” It is hard to avoid the conclusion that she wanted the good publicity for herself and – less selfishly – for Harvard Divinity School, then undergoing painful discussions about its future.

And yet, once again, a word of caution is in order. We should be careful when assigning blame and criticism when discussing forgeries. In Veritas, Sabar to some extent portrays Walter Fritz far more sympathetically than he treats Karen King. Sabar investigates and finds credible Fritz’s claim to have been raped by a Catholic priest as a child. “Fritz was never a believing Christian,” Sabar writes. “But the Gnostic gospels gave him the vocabulary to simultaneously skewer the Church for its sins and absolve his mother of hers.” Beyond his childhood, though, Fritz should not be a sympathetic character. He swindled his friends and business contacts, stole items from a museum, and promoted pornography (as Sabar says, “adult video is a legal business). Then he forged the manucript and carefully prepared King to accept its authenticity. Fritz was no master forger, but he played King just right, expressing just the right mixture of knowledge and ignorance, doubt and hope.

Why do we like con artists more than their victims? Because we enjoy watching a high-and-mighty publicity-seeking Harvard professor receive her comeuppance. Schadenfreude. We revel in King’s misfortune. As eager to play fast and loose with the facts as she appears in Veritas, King did not want to sully her academic reputation. She is the victim.

At one point, Sabar compares Fritz to Mark Hofmann, the master forger of fraudulent documents purportedly shedding light on the early history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In one of Hoffman’s forgeries, Martin Harris confirms Joseph Smith’s treasure-seeking activities and narrates that when he attempted to retrieve the golden plates, a spirit appeared, transformed into a “salamander,” “and struck the young seer several times. Hofmann’s creations convinced manuscript dealers and church leaders, who paid handsome sums to obtain them, in part to keep the discoveries under wraps. Prominent historians began using Hofmann’s documents as sources. Many observers enjoyed the extent to which Hofmann embarrased the church. He had convinced the highest-ranking leaders of the church that a “salamander” had whacked the young Joseph Smith!

Hofmann’s success unraveled. Facing mounting debts, he committed murder. A Mormon bishop and another bishop’s wife were killed by pipe bombs that he built, and a third bomb – intended for someone Hofmann feared would expose him – blew up in his own car. The individuals Hofmann murdered were the most obvious victims in the case, but the church, its leaders, and its members were also victims of his fraud.

Perhaps we have a native admiration for the scrappy if disreputable con artist who can pull a fast one on his apparent intellectual superiors. But put yourself in the shoes of the victims of such frauds. At the very least, Karen King deserves a measure of our sympathy and compassion.

My hesitation does not mean that I did not thoroughly enjoy reading Veritas. Sabar is a first-rate journalist and investigator. He doesn’t just leave no stone unturned. He finds all the stones and digs twenty feet under them. He’s a splendid writer as well. Even though I knew the rough outlines of the story, I couldn’t put the book down. Sabar’s reflections on the relationship between facts and faith (whether religious or another sort of ideology) are a cautionary tale for all scholars.