Today we welcome Janel Kragt Bakker to the Anxious Bench. Janel is Associate Professor of Mission, Evangelism, and Culture at Memphis Theological Seminary and the author of Sister Churches: American Congregations and Their Partners Abroad. Her current project responds to the culture wars in the U.S. with a missiology of repair, based on Jesus’ image of the basileia tou Theou (realm of God’s justice, love, and peace).

In the winter of 1998, I piled into a car with group of other humanities majors from Dordt College (now Dordt University), a liberal arts school in Northwest Iowa in the Reformed Christian tradition. We drove for twenty hours straight to Princeton, New Jersey, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Abraham Kuyper’s “Lectures on Calvinism,” given at Princeton Theological Seminary in 1898. Kuyper was a Dutch pastor, theologian, journalist, and politician, who served as the Netherland’s prime minister from 1901 to 1905. Standing out in my memory of the conference is a petition was circulated among attendees to recognize and repudiate Abraham Kuyper’s racist rhetoric, which was employed by many of his adherents in South African to scaffold apartheid. To my surprise at the time, my professors from Dordt College refused to sign the statement, arguing that Kuyper must be appreciated as a man of his time and that it was unfair to apply contemporary sentiments to a figure from another context. My professors were not alone; a number of pre-eminent Kuyper scholars, many representing the evangelical wing of the Reformed tradition in North America, have argued that, while some of Kuyper’s notions about race and gender are regrettable, Kuyper should be celebrated for his “deeper insights” outlining a distinctly Christian political philosophy and vision for society.

At Dordt College, our neo-Kuyperian professors educated us on the value of a “Reformed worldview” in which there is no divide between sacred and secular or nature and grace, and in which every domain of life is to be brought under the “lordship” of Jesus. A famous line from Kuyper’s speech to open the Free University in 1880, which he founded as an expression of this philosophy, was often quoted at Dordt: “There’s not a square inch in the whole domain of human existence over which Christ, who is Lord over all, does not exclaim, ‘Mine’!” Our professors contended that Kuyper provided a road map for Christians living in a pluralistic context. Christians should build distinctly Christian institutions and systems to promote the “kingdom of God,” while also working to support the common good.

After graduating from college, I moved to Washington D.C., ready to change the world as an ambassador of this kingdom of God. I began working for the Wilberforce Forum, the think tank of Chuck Colson’s Prison Fellowship. Coming to realize that Colson and his ilk interpreted “the Christian worldview” as a weapon to wield in the culture wars, while simultaneously being introduced to liberationist visions of Christian engagement in society in other venues, I soon left the position.

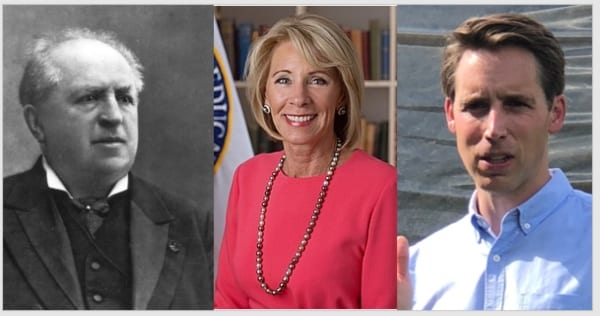

Though my ties to the Reformed tradition have thinned, sightings of names like “Abraham Kuyper” in The Atlantic and The New York Times still catch my eye. Reporters from these publications and others have noted how Trump-era Republican office-holders such as former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and Senator Josh Hawley have embraced Kuyper in service of their political agenda. In a 2017 speech to the American Renewal Project, then Missouri Attorney General Hawley invoked the “square inch” Kuyper quote to emphasize the authority of the Jesus over all aspects of human life. “We are called to take that message into every sphere of life that we touch, including the political realm,” Hawley said. “That is our charge. To take the Lordship of Christ, that message, into the public realm, and to seek the obedience of the nations. Of our nation!” In a bizarre interpretation of Pelagius, a fourth-century British monk who denied the doctrine of original sin and was condemned as a heretic, Hawley has argued that contemporary American society has fallen prey to the Pelagian heresy in the widespread belief that “liberty is the right to choose your own meaning” and that freedom means emancipating oneself “not just from God but from society, family, and tradition.” Pelagian philosophy, says Hawley, has made American society more hierarchical and elitist. Hawley’s solution is to “rebuild” a culture that protects the way of life of the American middle. “We must rebuild a democracy run not by the elites, but by the great middle of America, a democracy that allows the working man and woman to realize their God-given ability to govern themselves and help manage the life of his nation.”

Given Hawley’s actions as Senator, from his ardent support of President Trump’s falsehoods, his eagerness to disenfranchise millions of Black voters by challenging the Electoral College certification of the 2020 presidential election results, his expression of solidarity with insurrectionists who stormed that Capitol, and his refusal to drop his objections to the election certification after the attack, it seems apparent that Hawley’s “populism” is limited to right-wing white nationalists. Katherine Stewart, writing in the New York Times, names Hawley’s vision as “neo-Medieval,” containing the idea that “a right-minded elite of religiously pure individuals should aim to capture the levers of government, then use that power to rescue society from eternal darkness and reshape it in accord with a divinely-approved view of righteousness.”

In a 2020 speech at Hillsdale College, Secretary DeVos invoked Kuyper’s support for state funding of religious schools and insistence that authority over education belongs to families, not the state. DeVos declared that we could “fix education” by “go[ing] Dutch” in acknowledging the family as the “foundation for all other institutions” and instituting a voucher system for “school choice.” While state-funded parochial schools in the Netherlands are bound to strict non-discrimination policies in hiring and admissions, DeVos used her time as Secretary of Education to work to roll back protections for LGBTQ staff and students, weaken Title IX, and gut the most vulnerable public schools, serving largely black and brown populations. Though DeVos resigned from her position in the Trump administration last week in protest of Trump’s role in inciting a violent mob at the Capitol, she spent four years stoking the alliance between Trump and the Religious Right, parroting Trump’s racist dog whistles, and working to protect the perceived interests of white Christians above other groups. In her resignation last week, she incapacitated herself as a Cabinet member from holding Trump accountable.

More moderate admirers of Abraham Kuyper might quickly object to him being thrown under the bus with white Christian nationalists and cultural warriors like Charles Colson, Betsy DeVos, and Josh Hawley. They might point out how Kuyper’s political vision was pluralistic, with Protestant Christians making up one political constituency among others. Or they might insist that thinkers like Kuyper cannot be held responsible for how their ideas are misused by others.

Though I concede these points, I also maintain that we who inherit the legacies of white Christianity are called to acknowledge and seek to repair harm that has been committed on behalf of our traditions. Kuyper’s notion of the lordship of Jesus, articulated in the famous “square inch” quote, has more problems than it being used to baptize a wide range of questionable endeavors or to convey that Christians are the arbiters of the kingdom of God. The very notion of Jesus’ ownership of all things has imperialistic overtones, reflecting Kuyper’s Victorian-era white/European Protestant Christian triumphalism. While Kuyper celebrated cultural “pluriformity,” he maintained that outside of Europe and North America, most cultures had not benefited humanity as a whole, and he considered the life of African “races” to be the lowest form of human existence, with the bottom of humanity marked by blackness. In his so-called “ethical policy” introduced in 1901 in the Dutch-controlled East Indies, Kuyper described the responsibility of the Dutch toward native peoples as “guardianship,” since the Dutch were obligated to spend their superiority in service to God. Kuyper’s paternalism extended to women as well: he advocated for a householder franchise in the Netherlands wherein the father of each family unit would vote on behalf of his family.

Early in Kuyper’s career as a pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church, he led a secessionist movement on the basis of his desire to preserve doctrinal purity by requiring all church members and clergy to subscribe to the Reformed Confessions. His splinter church was known as the Doleantie, or “those who feel sorrow,” their identity based on their grievances against the state church. Kuyper was also well known for his affinity to de kleine luyden, or “the little people,” a group of middle-class orthodox Reformed farmers. While he cautioned them against agitation and encouraged them to be content instead with their heavenly reward, he worked to protect their political interests.

Even when taken on his own terms, there is much in Kuyper’s legacy to repudiate. And while it would be unfair to label Kuyper a white Christian nationalist, it is easy to see how his ideas could be employed in the service of white Christian nationalism, with its grievance ethos, its “color blindness” as a cover for its racism, its paternalism, its patriarchy, and its “populism” favoring white working-class interests.

In Sioux County, the corner of Northwest Iowa where Dordt University is located, Reformed Christians of Dutch ancestry are the majority. As a college student in the 1990s, I experienced Kuyperian values embedded in the community, with its network of Christian schools and social organizations and its centeredness on the institutions of the local church and nuclear family, as largely positive, if somewhat provincial. But from the vantage point of 2020, in light of Sioux County’s overwhelming support for Donald Trump, as well as my own exposure to stories from non-white, non-Reformed residents of Sioux County about their experiences of trauma and marginalization, I see the picture quite differently. For many in this community, the “Reformed worldview” seems to fit hand-in-glove with white identity politics.

Equity and political pluralism are not possible when power is not shared by minoritized communities and when social systems of oppression are not dismantled, in my current view. The basileia tou Theo that Jesus referenced so frequently in the gospel narratives is better represented by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other liberationists’ vision of the “beloved community” than by Kuyper’s vision of the “kingdom of God.” Jesus never described the basileia tou Theo as an empire which his followers were to build, but rather as the realm of God’s justice, love, and peace, where the first are last and the last are first—which his followers were invited to receive as a gift and welcome in the posture of children.

One of the neo-Kuyperian professors who led our Dordt College delegation to the conference commemorating Kuyper’s lectures at Princeton was known for his conviction that “ideas have legs.” Those of us rooted in particular religious traditions have a responsibility to reckon with and seek to repair the harm caused by our heroes as well as the harm committed in their names. A spirit of humility is essential in this reckoning, as we acknowledge that our actions too, which seem well-intentioned or even virtuous to us, may be judged harshly by outsiders or future generations. But the inevitability of our own shortcomings is not an excuse for refusing to tell the truth or failing to hold those who have abused power, ourselves included, to account. Thankfully, our traditions also contain a wealth of resources for the work of lament, repentance, solidarity, and repair.