I have a dilemma. I want to rave about a literary work that depends upon a wonderful twist of the plot, which you would never see coming until it actually hits you. But if I tell you the twist, or even that there is a twist, then I detract from the power of the story, even if I don’t actually ruin it. On the other hand, if I tell you nothing about the story at all, then perhaps you would never discover it. What on earth to do? Here is my compromise. I am going to tell you about a story, which is one of the Sherlock Holmes stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. But I will not actually tell you which one it is except in a link, which leaves you the option of following it or not.

Doyle often used US themes and ideas for his stories. Variously, he dealt with the Molly Maguires, with Chicago gangsters, and with Mormon Danite death squads roaming London. In some matters, he presented views that were amazingly liberal or radical for the time, and that was especially true in matters of race. In 1882, he had a transformational encounter with the leading Black American activist Henry Highland Garnet, a former slave and abolitionist, who shared with Doyle his radical perspective on recent US history.

We see that impact in several later Doyle stories. In the 1891 “The Five Orange Pips,” a series of dreadful crimes in England is traced back to the Ku Klux Klan, which is depicted as a cultish homicidal gang – as international terrorists, in fact. But to appreciate just how sneakily subversive the story is, you have to read it very carefully. To explain the Klan, Holmes refers to an American Encyclopedia which states that the organization was opposed by the US government, and by “the better classes of the community in the South.” Well, in that case, why was the Klan out to kill American fugitives in England? The victims are former Klan associates who have absconded with records revealing the organization’s inmost secrets, and these powerfully suggest that the “better classes” were in reality deeply involved in the movement, whatever the encyclopedia might have said. As Holmes explains: “You can understand that this register and diary may implicate some of the first men in the South, and that there may be many who will not sleep easy at night until it is recovered.” Hmm, I wonder what real life Southern leaders – or indeed, what esteemed Confederate veterans – we are meant to think of as being so desperate to conceal their secret Klan involvement?

Do note that the story never overtly points out the contradiction between the “better classes” remark, and “the first men in the south.” Blink and you will miss it, but Doyle is subtly mocking the way in which official American histories and stolid encyclopedias are misleadingly trying to draw a sharp line to separate the terrorist violence of the Reconstruction years from the established power of the Democratic state regimes after 1877. That is a fascinating sidelight on the evolution of the Lost Cause mythology in these years. It is also pretty good for a story written only a decade or so after the end of Reconstruction. Just how much had Garnet told Doyle? The story’s American political context fits the date of that 1882 meeting much better than it does the actual publication date of 1891.

That brings me to the cryptic story that I want to discuss here, which was published in 1893, and I stress the date. The story centrally concerns race, and specifically relations between a black American man and a white woman. Both in the US and Britain at this time, racist ideas of white supremacy were very widespread, and were being given scientific support. Yet Holmes’s story assumes that the reader should have no negative feelings whatever towards mixed marriage, or to a mixed-race child (and a very dark-skinned child at that). When a character turns out to have highly liberal and accepting opinions on such issues, Dr. Watson is delighted to observe the fact, and the reader is encouraged to share his “stand up and cheer” position. For the time, this is mind-boggling. The story had to have a couple of small but significant edits before it could be published in the US.

The story in question is sadly under-rated, and is not as often read or dramatized as some. I don’t think there has ever been a film version (Sorry, I see there is a 1921 short: happy centennial!) For much of its history, the story in question was dismissed as minor throwaway Holmesiana. That is grossly unfair. Its racial message apart, it is perhaps the nearest thing to a comic story of Holmes, where he turns out to have read the situation totally and embarrassingly wrongly, and is duly penitent for his stupidity. It’s really funny.

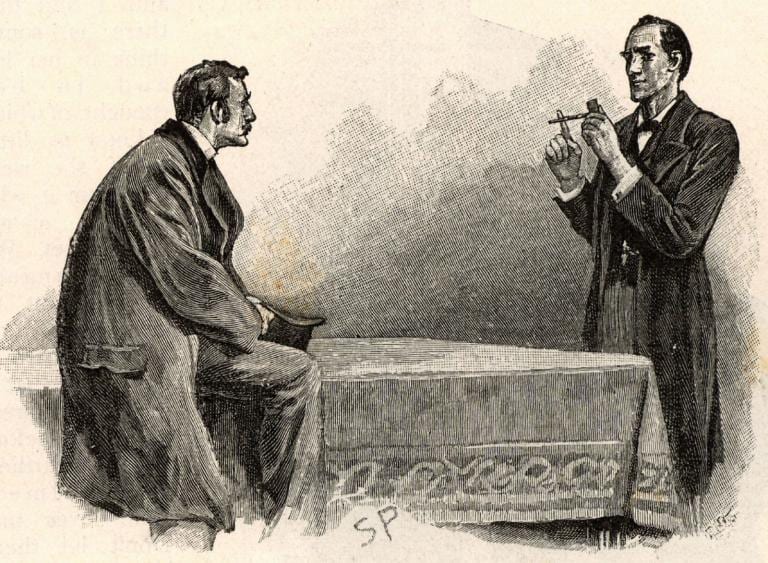

If you decide you want to read the story, even though you will now know the plot twist, then please follow this link. You can read more about it here. And do see the illustration.

We often hear about authors being denounced for expressing racist ideas in their work, which for some raises questions about how or even whether they should still be read today. How very pleasant, then, to have the opposite issue, of highlighting a long dead author who by the standards of 2021 is self-evidently right.

On a somewhat related matter, for connoisseurs of the Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock series, one great line of my Cryptic Story features prominently in the 2017 episode of “The Six Thatchers.” I’m not sure that even the obsessive Sherlock fans appreciated all the resonances in that reference, so let me explain. Bear with me on this one, it’s devious:

1.My original Cryptic Story takes place in Norbury. At the end, Sherlock asks Watson to use the name as a call to modesty: “if it should ever strike you that I am getting a little over-confident in my powers, or giving less pains to a case than it deserves, kindly whisper ‘Norbury’ in my ear, and I shall be infinitely obliged to you.”

2.Fast forward to the twentieth century, IN REAL LIFE, when probably the most dangerous and effective Soviet spy in Britain was Melita Norwood. She was a seemingly bland, harmless, and even dowdy middle-aged secretary, who had a kind of secret identity. For several decades. she was passing key secrets to the Soviets. She was exposed in 1999.

3.In the episode of “The Six Thatches,” Sherlock meets a seemingly bland, harmless, and even dowdy middle-aged secretary, named Vivian Norbury, who had a kind of secret identity. She turns out to be a lethal assassin, who kills Mary Watson. Her career, like her name, was clearly inspired by Melita Norwood.

4.At the end of “The Six Thatchers,” Sherlock asks Mrs Hudson, “If you ever think I’m becoming a bit full of myself. Cocky or overconfident. Would you just say the word “Norbury” to me. Would you? … I’d be very grateful.”

So somebody else read that Cryptic Story.