My middle-school-aged son once described what I do teaching honors’ college classes as sitting around with students asking, “Does anything mean anything?”

People in higher-ed humanities do talk quite a bit about meaning making. Indeed, our efforts in that direction are one means to name the value of what we do in contrast to, say, STEM disciplines, where parents may imagine they see tuition payoffs more immediately.

The question also dips into territory usually understood as belonging to religion, or at least spirituality. I’m interested in the way one university now makes a virtue of that proximity. Cornell University has resettled its interfaith office, Cornell United Religious Works, or CURW, under the auspices of its Office of Spirituality and Meaning Making, or OSMM. I’ll take a stab at making meaning out of that development.

Cornell was founded as a non-sectarian university, a land-grant institution distinguished in at least two ways from nineteenth-century comparables: it was not affiliated with a church or religious body, nor would it just match other big state universities born of the 1862 Morrill Act. This did not mean the university excluded believers, though its status did not necessarily imply genial neutrality either. Ezra Cornell’s co-founder Andrew Dickson White wrote a popular volume, a History of the Warfare of Science with Theology,whose title says pretty much what White understood as the relationship between the two. When Ezra pledged he “would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study,” theology or religion were not favored among that any. By the late twentieth century, students could put together religion-relevant courses from across a few departments for a concentration, and a religious studies major was added in 1992.

The real presence of religion on campus owes much to the donation of Myron Taylor, alumni industrialist and diplomat, ambassador to the Vatican during World War II. His funds put his own name on Cornell’s neogothic law school and library. His wife Anabel’s name adorns the adjoining edifice dedicated to CURW undertakings. Within Anabel Taylor Hall, CURW is proud to be the “oldest multi-faith college campus ministry organization in the nation,” founded in 1929.

Someone has to supervise the making of meaning at the only land-grant Ivy, and it’s no small good that the Associate Dean of Spirituality and Meaning Making is Oliver Goodrich, whom I had the honor to meet while at Gordon College. Goodrich recognizes the gravity of his office. But it is also not lost on him that the job title sounds fanciful with a “Willy Wonka” quality. Helping students make meaning is almost too good a job to be true. It is both like and unlike what humanities classroom spaces might be attempting.

To make some meaning of OSMM phenomenon, I can’t but begin with my own experience. If I had to map a faith journey, much of it would trace up and down the stairwells of Anabel Taylor. My family attended Mass there while I grew up in Ithaca, New York, not in a “parish” or a “church,” but at “Cornell Catholic Community,” which met in a large auditorium upstairs. I took for granted the normalcy of the way we did church, though visits to other Catholic churches told me otherwise. Something spiritually important happened to me there, though it wasn’t precisely Roman Catholic. It could have been the breezes of Vatican II blowing through the open windows of the auditorium, or it could have been the cross-currents that came of practicing faith in a space categorically ecumenical. Whatever it was, the answer was blowin’ in the wind–words we sang not seldom from the paper-bound worship booklets. Boy, I tried hard to make meaning of that. I had no idea how many times a man must look up before he can see the sky, or what the number had to do with God. I had less trouble with “Morning is broken,” since, after all, that song gives “praise for creation” and that initial blackbird is in a place called “Eden,” though why a blackbird should be the first fowl I could not fathom. Easier still to connect with creed and prayers was the guitar’s strumming, “to everything, turn, turn, turn,” because that of course was Ecclesiastes. My husband sometimes uses “Kumbaya” as an adjective for a kind of maudlin Christian brotherly sensibility but that irony is lost on me. Most church music of my early life sounded like Kumbaya. And there was something powerful in that plain singing, in thirsting for justice and holding each other’s hands through the Lord’s prayer, though I could not quite make out how pieces fit together in the faith we hold from the apostles.

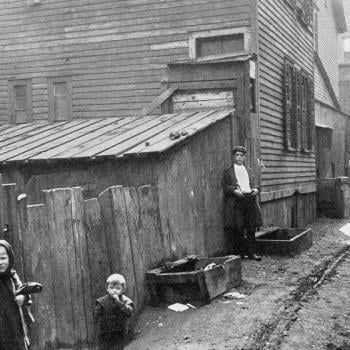

When my family went forth in peace, we went downstairs to the One World Room in the basement for a long coffee hour. I ate donuts under the watchful eyes of migrant farmworkers and protestors and children who looked hungry in the black-and-white photos wallpapering the space and reminding us, one more time before we left Anabel Taylor, that someone was crying, my Lord. When it was time to go home, we would either exit past the posters reminding us to boycott grapes or take the side door, walking through the shiny vacant spaces where Episcopalians and Quakers alternated services. Those Sundays made a lot of meaning for me, though I could not then say what it was.

When I got to college as a student there myself I still could not say what it was, except that for a while I hated it. That package of peace and praise felt to me like politics put in place of the Word of God. Wanting an OSMM but having none, I found a low-church Protestant congregation in town that picked up students from campus by buses. Spirituality and meaning was made for me off campus rather than on. Not that there was shortage of serious religious people at Cornell. The ones I got to know–on the church bus or in parachurch organizations–had various ways of understanding the warfare of arts-and-sciences with theology. Some were truculent; some were tranquil and earnest; some compartmentalized religion and study; some dismissed the academic parts of college life distraction or expedient for the future “tentmaking” that would enable evangelism.

OSMM comes under authority of the Dean of Students rather than in a school or administrative department, and so its goal is helping students explore spirituality and interpret their lives, rather than advancing aims of religious denominations or academic research. The integration it strives for is among the parts of students’ identities, religion intersecting with race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, or other aspects of whomever they understand themselves to be.

If I had had OSMM in my college years, I would have wanted help to put together not parts of identity but faith and learning. Putting together faith and learning, study and vocation, can give ways to connect the goals of college beyond research and future employment. Church-related colleges and universities tend to do this pretty well, or at least better than the offices I availed while at Cornell. Recognizing this need, other institutions have arrived at Cornell to assist with that integration, the study-center model at the Chesterton House or the pan-Ivy cultivation of future godly leaders through the Christian Union.

Making meaning that means anything requires passage of time. Students probably make better meaning when they can do it in community with people occupying different postures toward the passage of time, old people and young children who fill seats next to them in worship. That is, meaning making must reckon with one’s communities, chosen and not, rather than only one’s identities. I hope my gawky childhood presence served someone else’s spiritual good. Too, better meaning might be made not at once, not at one’s student life OSMM moments, but later, with recognition of how small and tentative, for all its heady assertion, college-years truth-handling can be.

I need to make a confession, that the OSMM inspires envy on two counts: first, envy for current students, that they have such an office to help them through university days, and second, for the dean, who has so dream-like a job as that, while I sit with students sometimes tempted to answer my son’s question in the negative.