In coming decades, we are going to hear a great deal about climate refugees, those people fleeing climate-driven environmental changes that have made their original homelands intolerable. Commonly, we associate them with the Global South, as Africans or Asians. But such a concept should not be so strange to Americans, as quite similar motives drove the migrants who laid the foundation of their country, and of their religious systems.

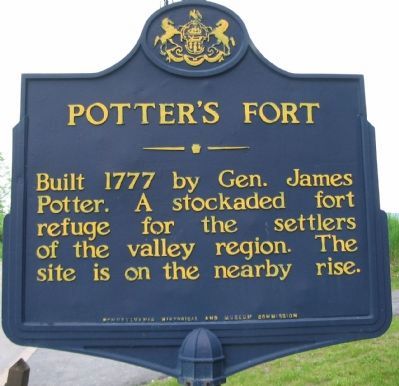

I spend part of my life in Central Pennsylvania, and I have posted about the early European settlement of this area in the mid-eighteenth century. One pioneer was James Potter, who discovered an “empire” in Centre County in the 1750s, and subsequently became an influential figure in Pennsylvania politics. Like most of the early white settlers, Potter came from Northern Ireland, and those early Scotch-Irish left a mighty imprint on the land, commemorated through countless place-names. From Pennsylvania, these restless populations spread west and south-west, through Kentucky and Tennessee, and eventually into the Upper South and Texas. You can map the emergence and growth of the Presbyterian tradition through their wanderings (and also of Freemasonry, but that is a different story). It’s a familiar tale for anyone interested in American ethnicity or religion, not to mention the country’s military traditions. These were combative folks: See Jim Webb’s aptly titled Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (2005).

Born in 1729, James Potter was just twelve when he arrived in North America in 1741, and that date demands our attention. The years from 1739 to 1742 marked a catastrophic downturn in the climate of the North Atlantic world, with incredible cold, deep snows far beyond any human memory, and all the attendant consequences of famine and pestilence. I write about this in my recent book Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval.

One of the areas most affected was Ireland, where outright famine raged. As a contemporary reported, “Multitudes have perished and are daily perishing under hedges and ditches, some of fluxes and some through downright cruel want.” At least 400,000 died from famine-related causes, one-sixth of the population, and some estimates of the death toll run higher. As a proportion of the population, the situation was actually worse than the notorious potato famine of the 1840s. Even the soundscape changed, as the mass death of Ireland’s birds left an uncanny silence: “No lark is left to wake the morn, / Or rouse the youth with early horn; / The blackbird’s melody is o’er.” One modern book on this event is aptly entitled Arctic Ireland.

Although the effects there were less dire, Scotland too suffered atrociously from cold and hunger, with a full-scale harvest crisis and a mortality peak. This was also a disastrous time for livestock, with the failure of fodder crops. The year 1740 marked a vicious new upsurge in the disease panzootic that would wipe out so many of Europe’s cattle. Just by way of explanation,a panzootic is like a pandemic, except it hits animals not people.

Is it any wonder that James Potter’s family fled to America in that horrendous year? Or that he was part of a much larger movement of Scotch-Irish in these same years, and shortly afterwards? Once they were settled in the new land, the pattern of chain migration took effect, as new arrivals called over to their friends and kinfolk.

However severe, 1741 was not the only climate-driven cataclysm. The years around 1680 were also dreadful, and the resulting crises drive rebellions, wars, and persecution of minorities, as well as an upsurge of apocalyptic sentiment. Many thousands of Europeans stood in desperate need of a distant refuge, which they found in the new colony of Pennsylvania (1682). Religious dissidents flooded in from Germany and the British Isles. Meanwhile, in Scotland, religious-based civil wars led to the mass persecution of hard-line Calvinist Covenanters. Driven out of the churches, they took to holding great worship services in the open air, where they heard the field preachers. That tradition remained, and was imported to the Americas by later Presbyterian exiles of the 1740s and afterward. If the model sounds familiar, then it of course became the basis of the great camp-meetings that manifested wherever those populations settled, in Western Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and the upland South.

Refugees need not be fleeing climate solely in the immediate sense of escaping extreme heat or rain, drought or rising seas. They can also be forced out by the indirect consequences, of what a contemporary writer on Ireland in 1740 described as “Contagion, Famine, Death, and deadly Shocks.” If the concept of climate refugee means anything whatever, then it certainly applies to a good number of these early settlers.

Besides my own book, Sam White studies such climate factors in the earlier stages of European settlement in A Cold Welcome: The Little Ice Age and Europe’s Encounter with North America (2017).