Today I’m happy to welcome to the Bench Jonathan W. Wilson, who holds a PhD in history from Syracuse University and bachelor’s degrees in history and business from LeTourneau University. An adjunct professor at universities in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Jonathan blogs about teaching history at Blue Book Diaries and tweets at @jnthnwwlsn.

Last month, I had the opportunity to try something new at my little Episcopal church.

I proposed an adult formation workshop in three sessions, to be held, both for convenience and for safety, on Zoom. (In another church tradition, “formation” might be translated as “discipleship.”) I offered to facilitate a conversation about historical thinking. I wanted to talk about history itself, rather than any specific historical topic.

At a time when public debates over history are fierce (and often very embarrassing), I’ve come to believe that one of the urgent tasks facing historians is to help our fellow citizens understand what history’s all about in the first place. We need to help people step back and gain some perspective before, or at least while, they charge into partisan debates.

But writing promotional materials for this workshop, trying to explain what “historical thinking” means, why it matters to Christians, and why people should care enough about it to attend, was challenging. Grasping for a provocative title, I picked “Seeing Dead People,” which I intended as a whimsical metaphor—although some people, as I should have foreseen, took it literally.

This would be an experiment. When the time came, six people took part.

Week 1: Understanding History

In the first session, which lasted an hour, I adapted a presentation I often give to undergraduate students at the beginning of a college course. The key goal was to introduce the idea that history is a process of investigation and reasoning based on evidence, not a take-it-or-leave-it restatement of received facts.

First, I asked participants to play a sort of parlor game I called “The History of the 2000s.” This was a simplified Zoom-friendly version of a classroom activity I have described elsewhere. Participants made lists of things—events, people, trends, cultural experiences, etc.—they would want to include in a future history of our last two decades. We compared lists and talked about why we chose the things we did. Then we debated how “true” a future history based on our combined list would be.

The point of this exercise was to grasp that creating any historical account involves a similar process of sifting through infinitely complex human experiences, making judgments about causation and significance.

From that point, it was easy to introduce the crucial distinction between primary and secondary sources as bases of historical knowledge. As usual, that involved stressing that primary sources are not necessarily more true than secondary sources; they’re simply more immediate to the past.

To illustrate that idea, I presented participants with two photographs.

First, I showed them Joseph Caxton’s 1839 daguerreotype of Philadelphia’s Central High School, which may be the first photograph ever taken in the United States. As a photograph, I pointed out, this extraordinary source has a “realness” beyond anything we would get from a painting, drawing, or textual description. Yet what could we learn from it as a piece of historical evidence? Participants discussed possible answers to that question. The gist of most answers was “not much.” Then I showed them a skyline photograph I took myself a few years ago in Philadelphia. The image was far sharper and more detailed, but fundamentally, participants observed, its limitations as a primary source were similar.

I summed up this session with a set of basic principles for historical thinking: History is not the same thing as the past. No single story can be the final word; no human has a God’s-eye view of the past. However, facts plus a valid interpretation can equal imperfect (or incomplete) truth.

Week 2: Understanding Historical Controversies

In the second session, I wanted to present a more explicitly Christian perspective on historical thinking. I also planned (with some anxiety) to tackle the problem of politically contested histories.

Invoking our Episcopal tradition, I presented participants with two of the questions in the baptismal covenant printed in the Book of Common Prayer. These questions, along with others, are put to the entire congregation whenever someone is baptized or confirmed in the Episcopal Church: “Will you seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbor as yourself?” and “Will you strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being?”

(The appointed response to each question is “I will, with God’s help.”)

I asked participants to reflect on what it would look like for a work of history to help us seek Christ in all persons, strive for justice and peace, or respect the dignity of every human being. How could a historian help us uphold those vows?

Eventually, I used this discussion as an excuse to talk about the difference between a “great man” approach to history and the impulse of many contemporary historians to write “history from below,” recognizing the importance of ordinary and marginalized people.

Finally, we turned to assessing historical controversies.

Here I introduced another conceptual tool, the “Five Cs of Historical Thinking” identified by Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke: change over time, context, causality, contingency, and complexity. Then I showed participants a couple of potentially tendentious (but not explicitly partisan) popular historical claims. I invited participants to assess how well these claims exemplified each of the Five Cs.

Participants thoughtfully discussed both strengths and weaknesses of each claim. In the process, they effectively demonstrated that good historical thinking can be as much about the virtues of the reader as about those of the text—and can’t always be reduced to a right-or-wrong proposition about accuracy.

Week 3: Putting History to Use

In our final session, returning to the difference between primary and secondary sources, I tried to explain how archival research actually works.

To anchor this discussion, I showed a photograph of researchers working in a special-collections reading room. I pointed out the Hollinger boxes in the photograph and explained their function. I noted that the researchers, contrary to popular expectation, weren’t wearing gloves. And I fielded a question from a participant who astutely observed that one of the researchers seemed to be taking a digital photograph of a manuscript.

Then I asked participants what they would look for in a book—say, one they found on a shelf at Barnes and Noble—as specific indications of thoughtfully conducted secondary and primary source research. We discussed features like endnotes, bibliographies and bibliographic essays, translator’s notes, and acknowledgments. I stressed the last feature as a tool for assessing whether an author participated in scholarly discussions, i.e., paid attention to the work of other experts.

(This led helpfully to a participant’s question about what I thought of authors like Doris Kearns Goodwin, Stephen Ambrose, and David McCullough, whose work, she observed, seemed to be based on extensive research but not necessarily much engagement with scholarly debates.)

Finally, we turned to the great challenge of this whole workshop series: history and Christian spirituality.

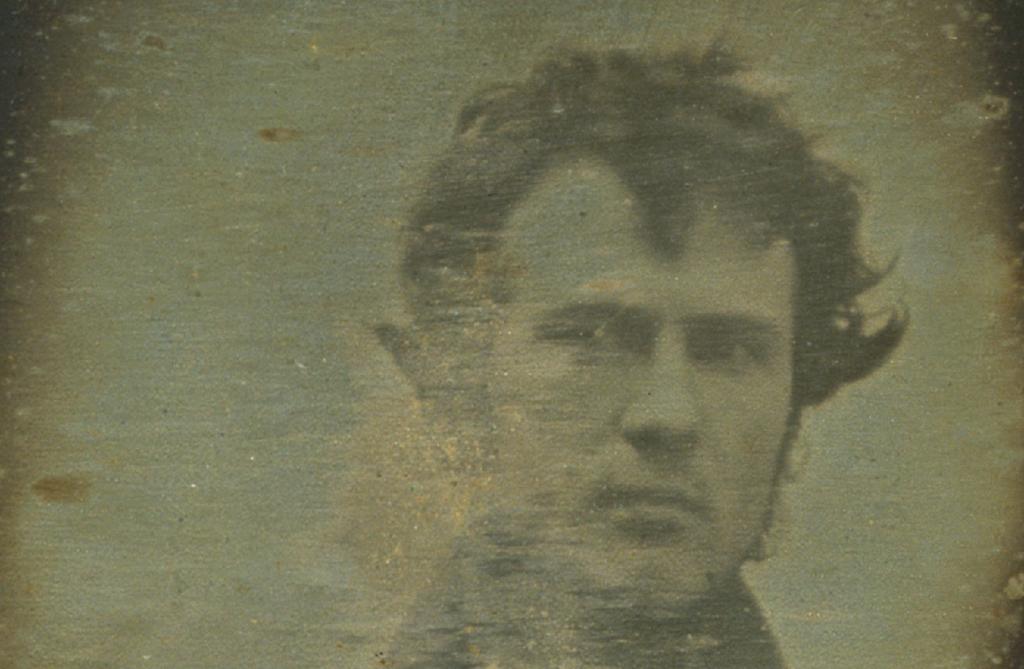

Returning to antebellum Philadelphia, I showed participants what may be the first American selfie, a daguerreotype made by Robert Cornelius, then about thirty years old, in the yard of his family’s lamp store in the fall of 1839.

I asked how people experienced this amazing image—what impressions it gave them. Some observed that it feels strangely fresh; we know the man in the photograph has been dead for generations, but his eye contact is electrifying. One participant also observed, however, that we see young Cornelius through an eerie scrim of darkness and wear.

I proposed that history’s proper relation to our spiritual practices may be a matter of truly feeling the reality of the people of the past, as when we feel the weight of Robert Cornelius’s reality (albeit “through a glass, darkly”) through his self-portrait.

Anglican spirituality especially stresses the implications of the sacraments and of Christ’s incarnation: God’s presence in tangible and mundane human life. Though long dead, Robert Cornelius, we believe, is made in the image of God, and he also shares with us the same humanity that Christ shared. That fundamental fact is of profound spiritual importance whenever we encounter anyone from the past, whatever else we may think of their character.

To recognize this from a Christian standpoint, I suggested, is a way of participating in the activity history teachers know as historical empathy. So I explained Jason Endacott’s and Sarah Brooks’s model for historical empathy as a three-step process, in which we study context, take a perspective, and connect emotionally (through similarity and difference).

Evaluations

My main source of regret about this series is that it ended up being too short. Each topic, I thought, had a lot of promise, and many of the approaches I tried for broaching these topics was basically successful considering the time constraint. But the series could easily have been a full weeklong seminar retreat—ideally with time allowed for reading, reflection, and prayer.

Upon consideration, my wish for this event is that “Seeing Dead People” might somehow, someday, become an early pilot program for something more ambitious. Exactly how that might work, I’m not sure; I think most of the content is sound enough, but it’s hard to imagine successfully marketing a larger version of this event. Merely being able to run it as a three-hour series on Zoom at my local church this year was probably a fluke.

In any case, any expanded program would be much better if it involved more than one facilitator as well as opportunities for hands-on activities.

I’m left, then, thinking that “Seeing Dead People” is not so much a model for future success as a question aimed at other Christian history educators.

Can we try a variety of experiments like this? Can we find ways to bring historical investigation into the life of the church as something more than an instrument of adversarial apologetics or politics? Conversely, can our churches be dissemination points for humane historical thinking in our larger communities?

I hope I’ll have opportunities to collaborate with other history communicators on such projects in the future.