Around the world, the stunning violence of September 11 cast a long shadow over the remaining years of the twentieth century. And no, that is not a typo for the 21st. For many people, above all in Latin America but also in Europe, the events of September 11, 1973 took a very long time to process and comprehend. For the Left – broadly defined – those events changed everything. In its way, that other September 11 likewise remade the world.

In 1970, Chile democratically elected Marxist Salvador Allende as its president. Many in Chile were alarmed at the prospect of another Cuba in the hemisphere, fears that were wholly shared by the US administration and its intelligence services. The US contributed to the economic destabilization of the country. Meanwhile, the radical Left became ever stronger in Chile, and developed armed guerrilla structures. The armed forces clamored for action. The inevitable coup d’etat occurred on September 11, 1973, when Allende killed himself. In the resulting Rightist repression, some 3,200 were killed or disappeared, and tens of thousands were tortured. To put that in context, Chile at the time had a population of just ten million, just one twentieth of that of the US. Chile’s new military dictator, Augusto Pinochet, remained in power until 1990.

The impact of this affair is difficult for North Americans to understand. Embroiled as they were at this time in the Watergate crisis, and followed so shortly afterward by the Yom Kippur war and the global oil crisis, they had a great many other things on their minds. If they did notice Chile at all, it was in the context of another CIA horror story to add to the existing roster of complaints awaiting investigation.

Matters were very different around the world. Chile – and September 11 – offered a stark warning for anyone on the Left, and by no means on the extreme Left, in Argentina, in Mexico, in Italy, in Germany, in Britain, and even in the Soviet Union. Ever since the late nineteenth century, Socialists and Communists had argued at length about the way forward, and the necessity of using violence and physical force, as opposed to democratic means. For a surprising number on the left, Chile settled the issue. The armed road, it now appeared, was the only road. Democracy could not produce socialism. Others agreed that the danger from Chile-style coups was intense, but that democracy might just still work, if Left parties totally rethought their approaches. But across the spectrum, the Chile coup detonated a profound reorientation, even an ideological revolution.

Not surprisingly, there was some myth-making in this analysis. In media reports, Chile was depicted as a kind of eternal European democracy almost on British or Swiss lines, and the implication was that if the army could launch a coup here, that could happen anywhere. In reality, the country had a military dictatorship from 1924 through 1932, and the Chilean military remained closely attuned to political matters long afterward.

The Chilean coup of September 11 had its effects far afield. One direct consequence was the emergence of Euro-Communism, as Europe’s powerful Communist parties desperately realized they would absolutely have to have the support of Socialist and centrist allies if they hoped to withstand the brutal coups they would face if they came to power in France, in Italy, in Spain….. Hence the sudden Communist moves to moderation, cooperation, and pluralism, and the prospect of broad Left alliances of a kind that terrified the US. If Communists were serving in European governments, even wearing Euro-Communist smiley faces, how could those countries continue as trusted members of NATO?

At the same time, the trend to a “historic compromise” alarmed the Soviets, who saw the Western Communist Parties slipping from their tight control. Still more perilous, that combination of democracy and pluralism sounded horribly familiar: was that not what Czechoslovakia’s Communist reformers had tried to do in that country in 1968? That movement ended with a full scale Warsaw Pact invasion, and traumatic images of Soviet tanks on the streets of Prague. If France and Italy went Euro-Communist, what was to prevent those ideas sneaking back into the eastern Bloc, to taint the parties of Poland, Hungary, and (again) Czechoslovakia? Those Soviet hardliners were right to be afraid. Many years later, Mikhail Gorbachev cited Euro-Communism as a major influence on the ideas of glasnost and perestroika in the Soviet Union itself.

This was a real political revolution, and a fundamental reorientation of the political alignments and assumptions that had dominated Europe since 1945.

Such efforts at compromise were doubly necessary as Europe’s economies tanked during the 1973-1974 crisis, which so closely foreshadowed the disasters of 2007-2008. By 1976, Italian Communists had won over 34 percent of the vote for the country’s Parliament, making it very nearly the country’s largest party, and national power was in reach. But would the CIA and the army step in? The nightmare dominated the decade. France’s Communists topped 20 percent of the vote.

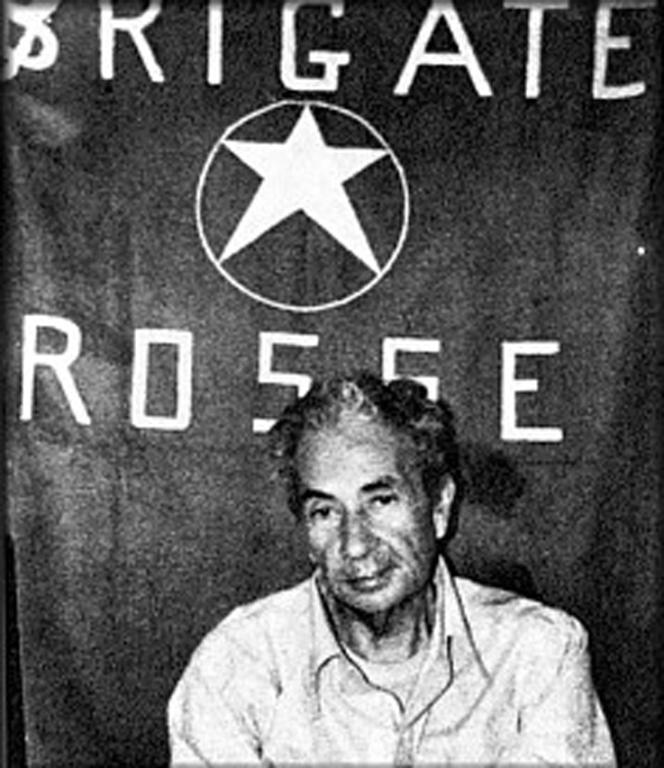

Others read the same Chilean lessons, but heard different messages. Instead of cooperating with other democratic parties, thought many, it was necessary to move wholeheartedly to armed revolution, to urban guerrilla movements. Such groups had been on the rise in the late 1960s, inspired by the 1966 film The Battle of Algiers and modeling themselves on its structures and tactics. But those movements now became far more overt, more militant, and committed to immediate armed struggle, here and now. These groups secured arms and funding from the Soviet bloc, sometimes mediated through Palestinian guerrilla groups. The best known example was Italy’s Red Brigades, which came close to reducing that country to a failed state by 1977-78. But there was also Germany’s Red Army Fraction, the focus of massive concern through mid-decade, until a bloody crisis in 1977.

Italy’s crisis reached an apocalyptic stage in 1978, with the kidnapping of Christian Democrat politician Aldo Moro, one of the country’s most powerful figures. Moro was engaged in complex negotiations with the Italian Euro-Communists to form a grand coalition, a Historic Compromise, which as we have seen was as much a nightmare for the Americans as the Soviets. The hunt for Moro lasted for an agonizing 54 days, involving something like a national lockdown, but he was ultimately fund murdered.

Just who was responsible remains a mystery. It was notionally the Red Brigades, but who were they? The movement began as enthusiastic leftist students dabbling in violence, but the 1978 kidnappers behaved more like highly trained and well armed special forces, who were acting on behalf of – who? The CIA? The Soviets? Both? Czechoslovak defectors claimed the Red Brigades were operated by that country’s intelligence service. Famously, the Red Brigades’ weapon of choice was the superb Czechoslovak-made Skorpion vz 61 machine pistol – although of itself, that proves nothing about political orientation. The CIA was quite capable of issuing such weapons to its proxies in order to cast blame on the Eastern Bloc. Did the terrorists themselves know who was actually directing them? Eric Ambler, who knew the intelligence world well, famously wrote in 1939 that “The important thing to know about an assassination or an attempted assassination is not who fired the shot, but who paid for the bullet.”

If not actually a coup in its own right, the Moro crisis grew directly and even inevitably out of responses to the Chilean trauma.

Just as hard core Leftists now contemplated the prospect of armed revolution, so armies, police, and security forces now looked to Chile and that earlier September 11 to see how they might be required to intervene against Marxist takeovers. This meant studying counter-insurgency theory – sometimes, by watching Battle of Algiers many, many, times, and learning about what the French had termed “dirty war” tactics. This involved extensive interrogation and torture, as well as covert assassination, death squad tactics, and illegal “disappearances.”

Even in Britain, as the economic situation grew parlous between 1973 and 1976, rumors of military coups and intelligence dirty tricks ran riot. Recalling how the Chilean army had stuffed suspects into the national football stadium for torture and interrogation, British journalists asked semi-seriously whether we could expect the same thing soon in London’s Wembley Stadium.

The other leading “students” of September 11 were in Argentina, where guerrilla groups now became highly effective and deadly. Their activities were summarily halted by a military coup in that country in 1976, which began a dirty war that killed perhaps tens of thousands. On a far smaller scale, dirty wars also proceeded in Uruguay, Brazil, and in Mexico. The concept of the death squad now gained international notoriety, and so did the word “disappear,” used as a transitive verb: you disappeared somebody. Obviously, this was not all an offshoot of the Chilean affair: the Mexican dirty war had been in progress for several years, as had repression in Brazil. But the events of September 11 gave a massive new urgency both to the revolutionaries, and to the agents of repression.

Purges of leftists ranged far beyond the borders of the countries immediately affected. One such assassination struck in the US itself, in a now-forgotten act of incredibly brazen international terrorism. In September 1976, the Chilean secret police DINA murdered regime opponent Orlando Letelier in a car bomb attack carried out on Washington’s Embassy Row.

When al-Qaeda struck New York and Washington in 2001, countless observers realized immediately that “September 11” marked the end of one era, and the beginning of another. Little noticed in this commentary were the remarks, opinion pieces, and letters by Latin Americans, who complained that they had had their own September 11, and nobody seemed to care about it. They had an excellent point.

That is worth remembering as we approach the twentieth anniversary of our own day of disaster.