As a devout Halloweenie, I regard it as my fundamental duty to recommend at least one essential film for the season. Although I have a number of strong candidates, I will focus on one magnificent example, which is simply a classic. That is the Korean film The Wailing (2016), directed by Na Hong-jin.

My relationship with the horror genre goes back many years, to the time when my wonderfully generous/irresponsible mother decided there was no harm in me watching very scary films at an early age. Based on that long experience, my standards for horror films are exceedingly high. In choosing this recommendation, I battle several other rival candidates, above all Ari Aster’s astonishing Hereditary (2018), and older classics like Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987). But credit where credit is due. I owe the present reference to a comment by Mr. Aaron Belz on a recent post of mine. As Aaron remarked earlier this week, The Wailing is “a 2016 Korean horror movie that makes great use of scriptural allusion. I would recommend it, but it’s very, very gory.” He is dead right on all counts. He reminded me of how very much I had enjoyed The Wailing when I first saw it, and was bowled over by it. Hence the present post.

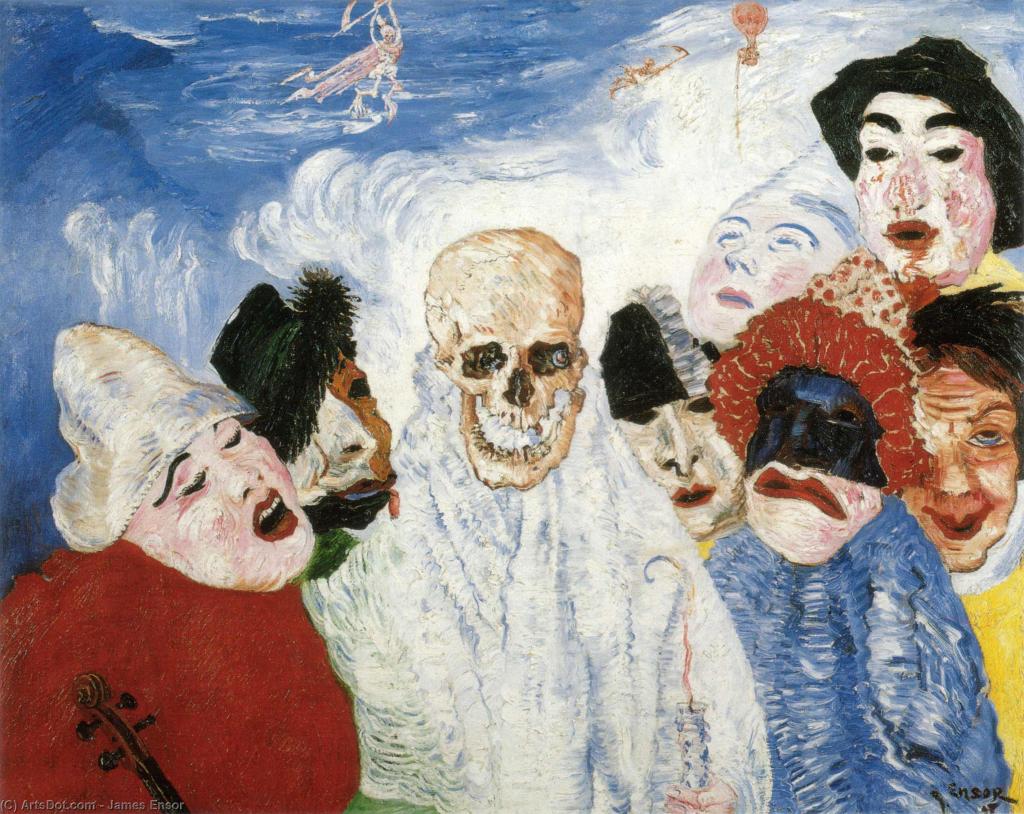

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897)

Appropriately for this particular Patheos site, I choose a film not just because it is artistically superb, but because it speaks to specifically religious issues and debates. The whole basic concept of Hereditary, for instance, grows out of wacko theories about Satanism and Ritual Abuse that were rampant in the 1980s and 1990s, and the idea of “hereditary” or multi-generational Satanic dynasties (not, of course, that the modern day film-makers believe any of this stuff). That in turn became intertwined with all the meshugas about Multiple Personality Disorder. And sadly, evangelical and charismatic Christians were among the main proponents of such toxic foolishness, which destroyed many real-world families. In the case of The Wailing, the religious references are so accumulated and overwhelming that the film could in itself serve as a central textbook for a whole course on Korean religion and religiosity, and by no means only Korean.

I won’t say much about the plot of The Wailing, and I strongly advise against reading any detailed plot summary: there are so many genuinely surprising plot twists. Save reading the summary until after you have seen the film. But here are a couple of general points.

First, the title, which in Korean is Gokseong. That is a real place, located way off in the country’s far south-west, a lovely but remote rural area that we might think of as the boonies. But the name also signifies “making noise” or wailing, a pun that many reviewers missed. It is almost like watching a US horror film that deliberately chooses a location in Erie, Pennsylvania, mainly because the name sounds like the word eerie. In the case of Gokseong, the film’s use of scenery and landscape is very impressive, often recalling Kubrick’s The Shining.

To describe the plot of The Wailing is to make it sound like a hundred other run of the mill pieces. A detective investigates spooky goings on in a small village: so what? But that is wildly inadequate. Much like Korea itself, the story is a multi-layered conversation between religious traditions, between Catholic and Evangelical Christianity, with Buddhism, and also with the shamanistic faith that remains so present, if often underground. In this film, the shaman looks rather more like a televangelist than a humble peasant practitioner. So we are dealing with demons? Fine, what sort? What kind of religious intervention might work against them? Are these ghosts, or spirits of Hell? Are they the living dead, or zombies? And here is a seriously alarming question: what if none of the alleged experts attempting to respond to the surging problems actually have a clue what is going on? What if the local version of Dr. Van Helsing is in fact flying blind? Even worse, the local Catholic priest officially declares that this one is just beyond the church’s capacity to help.

Again, how much of what we think is happening actually is? How much is paranoid delusion? Which characters are in reality anything like what they appear? In the words of Aja Romano, “Are the residents of the town being systematically poisoned with a drug that causes them to become frenzied, savage killers? Are they being cursed? Or is it both, and for what reason?”

Be warned: the film plays tricks with you and your expectations, and many scenes play once for humor, and then for horror. The director likes to lead you astray.

The story is gorgeously literate and allusive. At every stage, it is littered with overt and covert references to mainstream religious traditions, very much including Christianity: strange and terrible things may happen before the cock crows three times. Ed Travis called the film “religious horror of the highest order.” But watching the film also makes you realize how much Western horror is saturated in Christian assumptions, most obviously with the use of the cross against vampires. But now imagine yourself in a setting where you don’t fully understand all the ramifications of that folklore and myth. It’s disorienting, isn’t it? Just how are those Korean people reading their Bibles differently from their Western counterparts?

When asked why he chose these religious themes, director Na confirmed that he was very interested in issues of faith, but that he stands at an intersection of competing currents, much like the film itself:

I chose religion because I believed that no areas of study or school of philosophy could answer my question mentioned earlier. I’m a Christian, and if I didn’t believe in the God from the Bible to begin with, I would have told this story in an entirely different way. Perhaps I could have answered the question with scientific reasoning. But I’m not very devout practitioner like the rest of my family, participating in missionary works and such. I sometimes find myself agreeing to the concepts and comments that deny the existence of God. When making important decisions, I seek counseling from the Buddhist monks at temples in the mountains and pray there as well.

On a final note, it amazes me that the Korean film industry became so very, very, good in a relatively short period at the end of the past century. Since then, they have produced masterpieces in so many genres, so it is not surprising that Korean film-makers have created world-class horror.

John Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare (1781)