I first met Kevin Cragg in March 2003, when he hosted my job interview at what was then still Bethel College. Those two days are still a blur in my mind, but two memories of Kevin stick out. First, while he asked good questions about my grad school research and supposed fields of teaching expertise, he was more interested in telling me about a first-year Western Civ course that he coordinated.

Second, I remember walking up a stairwell when Kevin suddenly sagged against the railing. At the time, it just struck me that he seemed somewhat frail for a man who was about to turn 58. It wasn’t until a few years after Kevin hired me that we learned that he was fighting Parkinson’s disease.

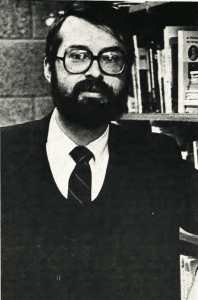

That struggle came to end early this past Sunday morning, when Kevin died at age 76 — almost two years after entering hospice care.

Born here in Minnesota just before the end of World War II, Kevin went to college at Wheaton, where he met his wife, Carole. After completing his graduate studies in ancient history and teaching college courses at what’s now Trinity International University, he came to Bethel in 1980, one of a series of hires by then-dean George Brushaber that would reshape Bethel’s faculty and programs.

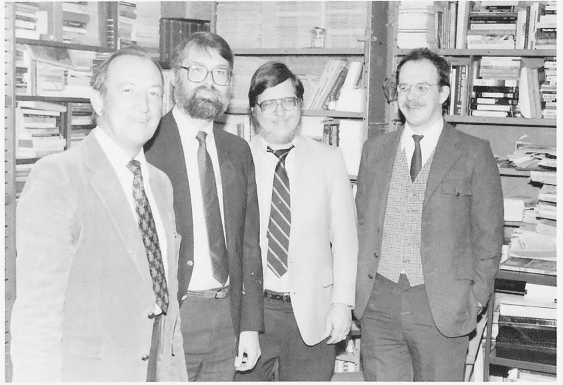

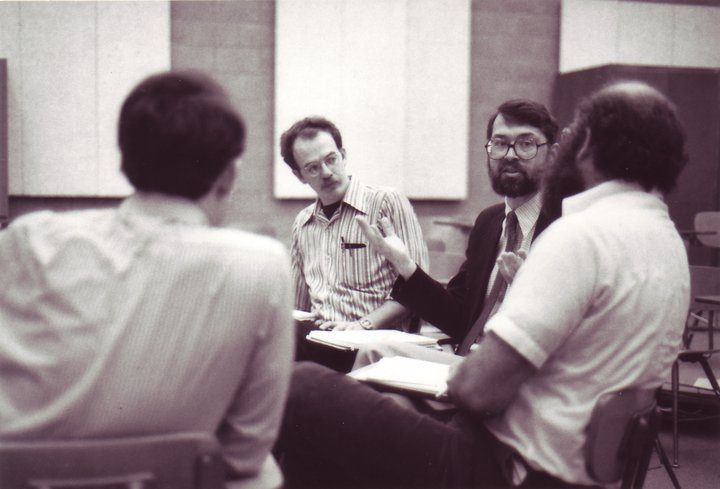

While he was a fixture of our history department for over thirty years, it was in the general education curriculum that Kevin made his most lasting mark on Bethel. About five years into his tenure, Bethel College revised its core curriculum. With European historian Neil Lettinga, literature scholar Dan Taylor, and New Testament expert Mike Holmes, Kevin spent January 1985 inventing a new first-year course called Christianity and Western Culture, which took the one-semester Western Civ course as the jumping-off point for a wide-ranging exploration of church history, philosophy, theology, art history, and politics. Not quite forty years later, CWC is still a pillar of our curriculum, the point in most students’ Bethel education when they first encounter the Christian liberal arts in all their breadth and depth, and a semester when they start to ask fundamental questions about themselves, their beliefs, and their relationship to the church and the world.

(Even as I draft this remembrance, I’m watching dozens of Bethel students take their last CWC exam, answering questions about vocabulary and readings that Kevin helped to pick, from scientists like Blaise Pascal and Isaac Newton to philosophers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant, social reformers like Mary Wollstonecraft and Frederick Douglass, and pastors like John Wesley and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.)

With another of Kevin’s former students, Sam Mulberry, I took over coordinating CWC about five years into my own time at Bethel, but Kevin remained on our teaching team. I can’t tell you how difficult it was to watch his physical decline begin to sap his abilities in the classroom. (I was astonished to listen to this recording of a 1988 lecture on the Byzantine Empire. The content and phrasing was familiar, but I had never heard his teaching voice pulse with such energy.) He held on until around 2013, when Sam produced an oral history documentary as a retirement tribute.

I’ve seen Kevin off and on since then, enough to have some sense of how difficult his last years were. When I visited him for the first time in hospice, I read him a draft of the introduction to my new book, knowing that one of the most brilliant minds I’ve known was still listening, even if Kevin was no longer able to communicate or even respond. The facility locked down for COVID a few weeks after that visit; as isolated as I’ve sometimes felt since 2020, I can’t begin to understand the loneliness Kevin knew in his last months.

Whenever I’ve grown angry with the cruelty of Kevin’s disease, I’ve found two sources of consolation. First, his habitual response whenever I’d mention that I was teaching about the world wars or the Holocaust that day my Modern Europe course. Shaking his head sadly, he’d simply mutter, “Gosh darn problem of evil.” Then second, a scripture that speaks to the hope of the Gospel, words that surely meant even more to Kevin than to me:

Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality. When this perishable body puts on imperishability, and this mortal body puts on immortality, then the saying that is written will be fulfilled:

“Death has been swallowed up in victory.”

“Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?” (1 Cor 15:51-55)

Much of what we do in CWC is helping students find themselves amid the historical and contemporary diversity of the Church, so I once asked Kevin what kind of Christian he was. His answer could have knocked me to the floor: “I guess I’m a fundamentalist.”

Now, Kevin had an amazing sense of humor. But it was more in the vein of a sly remark, an old-fashioned denominational joke, or those priceless moments when his normal dignity would give way to unabashed silliness — lecturing about Roman history in a toga, performing a rap about Augustine of Hippo, or suddenly growling like Chewbacca from Star Wars. Unlike me, he never resorted to sarcasm.

So I believed him: he was a fundamentalist. But in my mind’s eye I can only see his choice of word as “fundamentalist,” since Kevin was unlike anyone by that description I’d ever met.

He was no anti-intellectual or science skeptic. The recipient of graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan, he was one of the most curious, open-minded, and well-rounded scholars I ever knew. In addition to that Western Civ course and his upper-level surveys of ancient and medieval European history, he taught himself enough Minnesota history and environmental history to offer classes on both subjects. In fact, the latter course (now taught by Kevin’s former student Amy Poppinga) is still a pillar of the Science, Technology, and Society category in our gen ed curriculum, one of the few humanities classes to fulfill that requirement.

He was no legalist. I asked him early in my time at Bethel for advice on dealing with what seemed like an obvious case of plagiarism. “Did they admit to cheating?”, he asked. “No, but I’m sure they’re lying,” I insisted, holding up the website text that virtually matched the student’s assignment. “I’d still trust them,” he counseled. “If they’re not telling the truth… well, it’s all a part of their sanctification.” (And few Christians embodied saintliness like Kevin. In Sam’s video about him, our colleague AnneMarie Kooistra said he reminded her of Pope John Paul II, all the more so as he went through the physical suffering of his last years.)

Kevin was no Moral Majority culture warrior. I also asked him about his politics once, early on, and Kevin told me that he was a Republican, then added, “of the 1960 Minnesota variety.” Then he showed me a copy of that year’s platform for our state’s GOP, which included prominent planks about advancing civil rights, addressing unemployment, and protecting the environment.

He wasn’t a quietist, content to wait for heaven uncaring of the earth and its inhabitants. Over the weekend, Kevin’s son Luke recalled how his father “believed strongly in fairness and equality, and had a special concern for the the poor and the working class, our natural world, and Native Americans.” (Kevin and Carole lived on a reservation in Montana before he started his doctoral program.) Nor was he a Christian nationalist who assumed that his homeland was specially called or blessed by God. “I suspect American civilization only has about a hundred years left,” he told me during the Iraq War, then shrugged, “Even Rome lasted only a thousand years, after all.”

And he was no narrow sectarian. When he started at Bethel in 1980, Kevin told a reporter from the student newspaper that he’d worshipped with “practically every denomination at one time or another.” And while he and Carole ultimately settled into a Presbyterian congregation, their home featured an ecumenically impressive array of religious art, including reproductions of beautiful Orthodox icons.

So what kind of a “fundamentalist” was Kevin? I still feel better putting that term in quotation marks, but I can see at least some connection to the original fundamentalist movement.

Just last week in CWC, we happened to read a document from the first volume of The Fundamentals — not any of the original theological pamphlets, but the personal testimony from Dr. Howard Kelly. A medical school professor at Johns Hopkins University, Kelly shared his story of passing through modernism-inspired doubt to renewed belief in doctrines like Jesus’ divinity and his Virgin birth, bodily resurrection, and eventual return. Most of all, Kelly affirmed the inspiration of the Bible, a unique book that he found to be “really food for the spirit as bread is for the body” and “a consistent and wonderful revelation… of the character of God, a God far removed from any of my natural imaginings.”

And I’m sure Kevin believed all those things, too. But what brought my friend to mind was the next sentence in Kelly’s testimonial: “[The Bible] also reveals a tenderness and nearness of God in Christ which satisfies the heart’s longings, and shows me that the infinite God, Creator of the world, took our very nature upon Him that He might in infinite love be one with His people to redeem them.” That line evokes Kevin’s beloved Augustine, who started his Confessions (long a CWC staple) by wondering how a finite mortal could possibly dare to call upon the Maker of Heaven and Earth, yet concluded that this same God had “made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in you.”

Kevin believed the Bible to be truthful and the doctrines derived from it to be reliable, but as importantly, he believed that the Bible made personally, intimately known to sinful creatures their merciful and loving Creator. And in the process of learning the Word of that God, we are made different: more faithful, more hopeful, and more loving ourselves. Kelly might have been describing Kevin when he wrote of Christianity’s effect on his own life: “greater tenderness to [family and friends] and deeper interest in all men. It takes away the fear of death and creates a bond with those gone before.” Kevin was that kind of fundamentalist.

Or maybe he just meant that he emphasized only a few fundamental religious beliefs and kept second things second. Kevin didn’t put much stock in labels anyway; he preferred to take people as they came and listen to their particular stories.

But if I wanted to place him more precisely… I think Kevin was really what his former Bethel colleague Roger Olson might call a postfundamentalist evangelical: one of those Bible-believing, born-again Christians from the post-WWII Midwest confident that their religious convictions could survive extensive engagement with the secular world.

It’s easy for 21st century evangelicals like me to be dismissive of the mid-20th century neo-evangelical project — and Kevin would be the first to acknowledge its shortcomings and blind spots. But remembering the career of my mentor and friend reminds me that my own career is what it is because of evangelicals like him: Christian college grads who were able to thrive in secular universities, but rededicated their adult lives to advancing the cause of Christian higher education. (Kevin’s time at Wheaton overlapped with that of Mark Noll, who taught history with him at Trinity, and future Bethel colleagues like philosopher Don Postema and our recently retired president, Jay Barnes.) In Kevin’s case, that meant that a scholar who could surely have published multiple volumes on ancient Greece and Rome instead put out only two more general books (a church history text that emphasized the social history of ordinary Christians and an edited collection of world history writing) and spent over thirty years building curriculum and teaching courses in relative obscurity, unknown by most and utterly transformative for a few.

If I seem overly critical of evangelicalism in venues like this blog, it’s because I want to be a good steward of what people like Kevin tried to build: I want to leave the evangelical church and its colleges strengthened where they’re right, corrected where they’re in error, and reformed wherever they have gone amiss. If I agree that it’s imperative that we both de- and re-construct evangelicalism, it’s because I love Kevin Cragg and want to honor the memory of my favorite “fundamentalist.”