I have been talking about the very broad themes that unite empires throughout history. I’ll continue that here, and offer some specific applications from the imperial encounters of one of the best known examples, namely the Hebrew people.

Empires come in very different forms, but they have certain very broad characteristics in common, and those common features are what I will be discussing in coming posts. Let me list them in very rough form here. I offer ten broad points, although another writer might choose many more, and present a quite different list:

1.Empires need to maintain rule over territories that are geographically large, or indeed might be transcontinental or global. That places a high premium on building and maintaining systems of communication, which might mean roads or sea routes, with all the institutions that implies – ports, towns, entrepots.

2.Whether or not the empire in question intends this, those system virtually always generate new economic arrangements, as well as new social systems and hierarchies. Empires tend to breed merchants as well as proconsuls.

3.Empires need institutions of rule, which at the very minimum demand mechanisms for the collection of taxes and tribute. Some empires are content to rely largely on local middlemen, but most develop more elaborate and intrusive systems of rule and domination. Depending on the particular situation, such rule involves spreading bureaucratic systems, with the literacy that involves, as well as the language of the dominant power.

4.Even if empires do not demand the use of their own language, or some common lingua franca, such practices do result in such a linguistic spread, which may have lasting consequences. The longer the empire endures, that might drive older local languages into a marginal status, or indeed drive them out of use entirely.

5.The fact of empire generally (not inevitably) involves a cultural disparity or inequality between the ruler and the ruled, the core and the periphery. Depending on the scale of that gap, the effects on local societies might be enormous. Deliberately or not, empires tend to foster harmonization across the whole of the territories they rule, in terms of language, institutions, and social and economic arrangements. In some extreme examples, the new order might represent a revolutionary transformation, introducing urbanization, commerce, and even literacy itself.

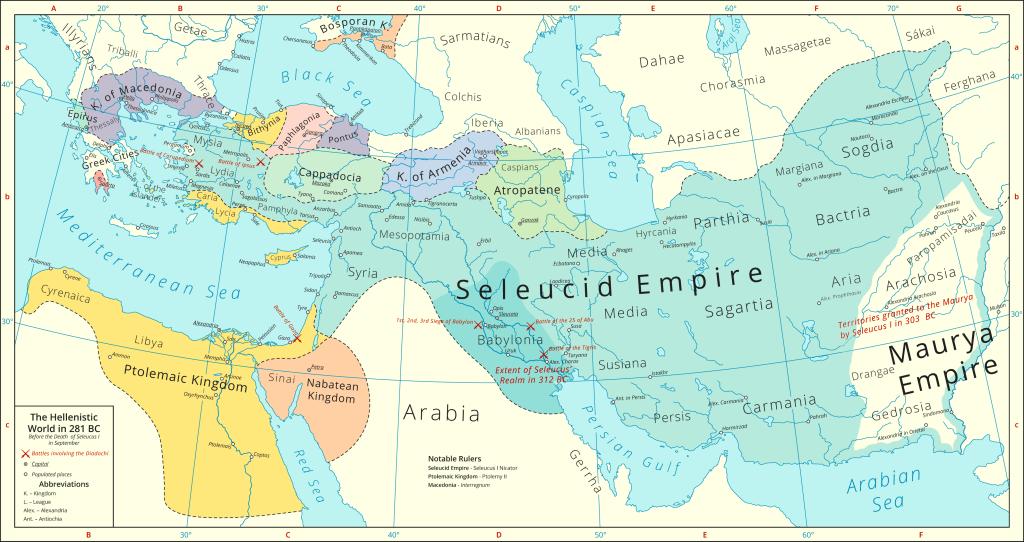

6.To reiterate the phrase yet again, empires differ greatly in how they address this issue, but they are often associated with the spread of new populations. These might be confined to administrators, but some create whole new worlds of settlers and colonists across territories they rule. Just to take the ancient Greek example, we can trace the proliferation of dozens of cities called Alexandria (or Philippi, or Antioch, or Seleucia) from Europe through the Middle East, and deep into Central Asia. Empires take symbolic possession of the lands they rule through acts of naming and renaming, mapping and remapping. Those settler/colonial centers serve as hubs to spread the new values, customs, and languages – and commonly, new religious realities. Cities commonly become theaters of imperial power, where great public works and monuments are displayed.

7.Of necessity, empires must depend on military strength, with all that implies about the role of the military in particular societies, the status of military elites, and the scale of resources they receive from the state. The military theme can transform the metropolitan society, by giving power to new elites, and by promoting violent and authoritarian values. Military service, often on a very wide geographical scale, profoundly affects the life-experience of ordinary people, and their geographical perceptions.

8.Empires create borders where, usually, none had existed before, and the fact of those borders constitutes a powerful cultural reality. Beyond fortifications, borders demand towns or trading centers, where influences from inside and outside the empire meet and interact, and often spread much further afield. Often, military needs provoke the relocation of hostile or restive populations to other parts of empire, again with the effect of cultural transmission. A great deal happens on these peripheries of the periphery.

9.Except in the immediate phase of conquest, empires must form some kind of relationship with local subordinate populations. Some govern through traditional elites. Some recruit local people as soldiers or administrators, and commonly use local groups or peoples as allied or surrogate forces. Some empires offer local people means of entering into participation in empire, and even joining the ruling elite. Other regimes maintain a strict and rigid segregation between rulers and ruled.

10.Different communities face a familiar range of decisions and dilemmas in responding to empires, with a well-known spectrum of types of accommodation or resistance. The exact course of action depends largely on the cultural resources available to the conquered and occupied, and this often finds expression in religious terms. That experience – whether of accommodation or resistance – often creates new identities, new consciousness, and can create new senses of nationality.

I present these ten points in very general terms, but let me explore them with reference to the well-known story of ancient Israel. So much of that story is incomprehensible except in terms of the encounter with the great empires of the day. In Egyptian and Assyrian times, that Israel was a buffer state, a contested borderland. The Babylonian empire deported many Hebrews to their metropolitan homeland, where those subjects encountered many new religious ideas and cultural ways. On being restored by the Persian Empire, those Hebrew developed radical new theologies about the nature and unity of God, and his willingness to work through people of any nation. Universalism was a product of that imperial contact.

That story is very familiar to anyone who studies the background of the Old Testament, but let me focus on the case of the Hellenistic Empire that ruled Palestine in the third and second centuries BC, the Seleucids, about whom I wrote at length in my 2017 book Crucible of Faith. Stretching as it did from Greece to what we would call Pakistan, the Seleucid Empire brought together a huge range of different cultures and religious traditions, and spread ideas and practices over this enormous area. The empire encouraged what it saw as an amiable syncretism, a merger of different deities and worship cults through common themes. In particular, this experience ensured that for many peoples once separated from each other, they thought and wrote in the Greek language, and applied Greek categories. That interaction revolutionized Judaism, even among those figures who bitterly resented that Greek rule.

In the second century BC, Jews rebelled against that imperial system, and in the process created a new sense of national identity, together with whole new structures of religious belief, above all through apocalyptic. The monstrous figure of evil portrayed in the book of Daniel, who is usually taken as a first draft of the Antichrist, is modeled very directly on the Seleucid emperor Antiochus Epiphanes. Commonly, Jews discussed their ideas through the Greek Septuagint translation of the Bible. As new Jewish kingdoms emerged, they modeled themselves entirely on the Seleucid rulers, adopting their symbols of power.

That new Judaism became the Jewish world that we know from the New Testament. Nobody who has ever read that text doubts the overwhelming significance of the Roman Empire in that story, at every point. Even the demons took the name “Legion.” But here is an interesting exercise. Look at the Gospels, and the Book of Acts. Then see the really key things that happen in places that are named for emperors or members of their families, whether Roman dynasts or Greeks before them. The list includes, at a minimum, Caesarea, Caesarea Philippi, and both Antiochs mentioned in Acts, not to mention Seleucia, Ptolemais, Philippi, and Thessalonica. It also includes the Sea or Lake of Tiberias, the name that the Romans had given to the Sea of Galilee a very short time before the events of the gospels. Apollos came from Alexandria. In the seven churches of the Book of Revelation, Laodicea and Philadelphia were both royal namesakes. People are literally walking in an imperial landscape.

Without that imperial context, Christianity – like Judaism – is incomprehensible.