What will happen if the Supreme Court reverses Roe v. Wade next month and gives states the power to set their own abortion policy? Many pro-life advocates believe that the end of Roe will be the key to saving unborn lives – the holy grail they’ve sought for decades. And many reproductive rights advocates expect it to lead to a horrific era of dangerous self-abortions and state policing of women’s bodies.

In reality, though, the practical results of the Supreme Court’s decision are likely to fall short of the predictions made on both sides of the abortion debate. The end of Roe will be less of a break with current trends on abortion policy than an exacerbation and continuation of them – and in that sense, it will ultimately prove disappointing to almost everyone on all sides of the abortion debate.

What are the false expectations that people have about what the reversal of Roe v. Wade will really mean?

False expectation #1: The end of Roe will mean the end of legal abortion in at least half the United States.

Many media outlets, following the Guttmacher Institute’s lead, have predicted that “26 states are certain or likely to ban abortion without Roe.” Of all the false expectations about Roe that I’ve heard, this one may come closest to the mark – but even here, the reality is likely to be a lot more complicated, and the results of Roe’s reversal less sweeping than many imagine.

(NB: To explain what exactly will happen when Roe v. Wade is reversed, I’m going to have to engage in some detailed policy analysis that will make this post a little longer than those you’ll typically see on this site. But I think this level of detail is worth reading, because it’s the only way I know to demonstrate exactly what will – and will not – happen after the Supreme Court rules in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization).

Thirteen states have “trigger laws” that will automatically cause near-total bans on abortion to go into effect within weeks of the time when Roe v. Wade is reversed.

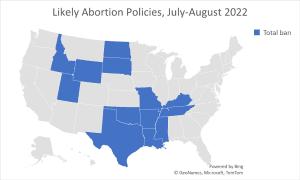

So, assuming that the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade at the end of June, we will probably see an abortion policy map that looks like this by the beginning of August:

While this map may appear to indicate that vast swaths of the country will be saving tens of thousands of unborn lives (or, depending on your perspective, denying abortion services to tens of thousands of women), this is not quite the reality.

Three of the states with “trigger laws” – Idaho, Oklahoma, and Texas – have already passed abortion restrictions that have effectively outlawed most abortions, so the effect of an additional “trigger ban” if Roe is overturned may be negligible. In addition, one state (Wyoming) performed so few abortions in 2017 (only 140 out of the nation’s 862,320 abortions) that a ban in Wyoming will have no measurable effect on the nation’s abortion rate. Likewise, South Dakota (another state with a “trigger law”) performed only 500 abortions in 2017, the latest year for which abortion statistics are available.

In fact, on closer inspection, it appears that most of the ten “trigger law” states that have not already banned most abortions have nevertheless adopted such severely restrictive abortion policies even without the reversal of Roe that an additional ban will be a less drastic change than many on both sides of the abortion debate may believe. For instance, all but one of those states already has a mandatory waiting period of at least 24 hours – which means that a person who wants an abortion must first schedule a counseling appointment at the clinic and then wait at least 24 hours (and, in some of these states, as long as 72 hours) before the abortion can be performed. None of the states in question provide Medicaid funding for elective abortions, and several restrict private insurance plans from covering abortion. Several of these states have only a single abortion clinic, and none of them have an abundance of abortion providers. In none of these states do the majority of women in the state live in a county with an abortion clinic. It is thus no surprise that all these states already have abortion rates that are well below the national average (which is an annual rate of 13.5 per 1,000 women of childbearing age). In fact, the average abortion rate in these ten states combined is only 5 per 1,000 women of childbearing age.

Collectively, therefore, these ten states account for only 4.7 percent of all abortions in the United States – or a total of 40,510 abortions in 2017. While it may seem like 40,000 abortions is a large number, the fact is that the number of abortions fell by 196,000 during the six years between 2011 and 2017 – that is, an average of 32,667 per year. In other words, even if none of the women in these affected states found alternative ways to get an abortion (which, of course, is a completely unrealistic expectation), and even if an average of 40,000 unborn lives were saved every year as a result, this decrease in the abortion rate would be barely more than the annual decrease in the abortion rate that we’ve already been seeing over the course of the last decade.

These ten states collectively have a total of 50 abortion providers, which is fewer than the number in Connecticut or New Jersey alone, and barely more than the number in Maryland. Since there were 1,587 abortion providers in the United States as of 2017, decreasing that number by 50 will not result in a drastic change to the nation’s abortion services – much to the chagrin of many pro-life advocates.

The loss of these abortion providers is likely to present an additional inconvenience – but not an insurmountable barrier – to many women seeking an abortion. Instead of driving to Fargo for an abortion, women in North Dakota will now have to travel to Minneapolis. Instead of getting an abortion in St. Louis, women in Missouri will now have to cross the river to one of the towns in western Illinois.

Some women, to be sure, will be affected more substantially. Women in Shreveport, Louisiana, for instance, may soon have to travel several hundred miles to reach an abortion clinic, whereas until now they have had access to abortion services in their own city (albeit with a required waiting period and other restrictions).

On the whole, though, the immediate effects of Roe v. Wade’s reversal will impose only marginally greater burdens on most women who live in the affected states than they already face through mandatory waiting periods and the denial of public funding for abortions. Women in the affected states already have to pay $500 out of their own pockets for a first-trimester abortion, schedule multiple visits to an abortion provider, and – in many cases – travel across the state for two or three hours to find an abortion provider. Now a surgical abortion will require them to travel a bit farther – potentially up to seven or eight hours farther in some cases. (If you look at the map above, you’ll probably see that women in east Texas and Louisiana may be the most significantly impacted). But abortion access in the United States has not been very equitably distributed since the end of the 1970s, and it has become even less so over the past decade. The end of Roe will only exacerbate current trends. Abortion will be prohibited in some states while being fully funded through Medicaid in others.

But, as you may have noticed, so far I have talked only about the immediate effects of Roe v. Wade’s reversal. What about its longer-term effects? Won’t additional states ban abortion in the months following the Supreme Court’s ruling?

The answer to that question is yes, although even in the long-term there may be fewer total abortion bans than some people think. In Alabama, there is likely to be a legal fight for the next few months, because the state passed an abortion ban in 2019 that was blocked by a federal court and is therefore unenforceable. The Alabama attorney general will almost certainly appeal that earlier court decision once the Supreme Court overturns Roe, and the state will likely win on appeal. Similar legal fights may occur in several other states, including Georgia and Ohio, which passed “Heartbeat Bills” in 2019 banning abortion after six weeks. Those bans were blocked by the courts at the time, but the end of Roe would give the states an opportunity to appeal. So, although abortion will not be illegal in Alabama, Georgia, or Ohio at the beginning of July, abortion restrictions that were passed in 2019 could go into effect in those states at some point later this year, depending on how quickly the courts rule. The same is true in South Carolina, where the state will no doubt spend part of this summer trying to secure a court ruling that will let it enforce its 6-week abortion ban.

In addition, some conservative states that do not currently have abortion bans may attempt to pass abortion prohibitions later this summer. Nebraska, for instance, is widely expected to convene a special legislative session this summer to create an abortion ban. In Kansas, where an earlier court ruling that the state’s constitution protects abortion rights has prevented the state from enacting a “trigger law,” the state’s residents are scheduled to vote on a referendum in August to amend the constitution to allow abortion restrictions. Indiana is taking a wait-and-see approach and will decide after the court decision whether it wants a 15-week ban, a 6-week ban, or a near-total ban on abortions.

Florida, which adopted a 15-week abortion ban this year, may experience conservative pressure to tighten that prohibition, since a 15-week ban still allows for at least 93 percent of the abortions that would have occurred without the restriction. But after passing a 15-week ban this spring, I’m not sure that the Florida legislature will be ready to immediately implement a stricter measure. Some states with 19th-century abortion statutes still on the books (such as Wisconsin) will probably be involved in prolonged legal wrangling over whether those statutes can still be used to shut down abortion clinics – unless, that is, the legislatures in those states act quickly to clarify the law. Some have predicted that abortion providers in Wisconsin could be prosecuted under the revived 19th-century statute, but the state’s governor and attorney general are Democrats who support abortion rights, and the attorney general has said that he will not use the 19th-century statute to prosecute abortion doctors.

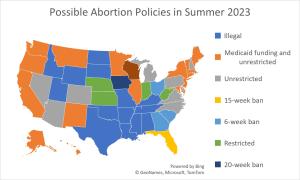

Perhaps, therefore, by the summer of 2023, the abortion policy map might look something like this:

A total of eighty abortion providers may be affected by the additional abortion restrictions that a total of eight states (Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, Ohio, South Carolina, and West Virginia) may implement in the year after Roe v. Wade is overturned. If Florida decides to pass a more sweeping abortion ban or if a few swing states (such as Pennsylvania or Wisconsin) decide to restrict abortion, the number of abortion providers who are affected will be substantially greater, but most likely, these things won’t happen. As it currently stands, it appears that 47 abortion providers were affected by the abortion prohibitions passed in three states this year, 50 additional abortion providers will be affected by the “trigger laws” that will go into effect immediately after Roe is overturned this summer, and possibly up to 80 additional abortion providers could be affected by changes introduced over the course of the next year. But even if all of these things happen – and if a total of 21 states adopt substantial abortion restrictions over the course of the next year – 1,410 of the nation’s 1,587 abortion providers will still not be directly affected by these laws.

In other words, even if 21 states outlaw most or all abortions and a few additional states (such as Florida) retain 15-week or 20-week bans, the number of abortion providers will decline by only 11 percent (and that includes the pre-Dobbs declines of 2021-22), and 1,410 abortion providers will still be in business. In actual fact, a projection of an 11 percent decline in the number of abortion providers is probably overly optimistic, because some of the states with the most liberal abortion policies are preparing to expand abortion services, and if they do, the new abortion clinics will offset some of the declines in the states that make abortion illegal.

False expectation #2: Hundreds of thousands of unborn lives will be saved as a result of overturning Roe v. Wade.

Abortion rates have been dropping for more than thirty years, and they are now even lower than they were at the time Roe v. Wade was issued. So, even without overturning Roe, abortion rates have decreased markedly, as I documented in an earlier post. How many more unborn lives will be saved as a result of overturning Roe?

Unfortunately for pro-life advocates, the probable answer is not very many. First, as I noted above, the states that are likely to prohibit abortion already have very low abortion rates. The first round of prohibitions in the summer of 2022 will affect fewer than 5 percent of the abortions in the United States, and even the prohibitions that may occur during the next year in up to eight additional states will have a direct impact on only a small percentage of the total number of abortions. Even the most optimistic predictions suggest that the current total number of abortion providers who will be put out of business as a result of all of the abortion prohibitions enacted during the next year is a lot less than the total number of current abortion providers in New York alone. So, the end of Roe v. Wade will hardly mean the end of legal surgical abortion in the United States.

But, of course, even if 130 abortion providers are put out of business over the course of the coming year, that does not mean that all of the women who would have had abortions at those facilities will choose life for their unborn children instead. The evidence suggests that many of them will choose to travel to out-of-state abortion clinics. In February of this year, a few months after Texas passed a 6-week abortion ban, clinics in New Mexico, Colorado, and Louisiana were reporting increases in demand for abortion services of up to 800 percent, which was due almost entirely to a surge of business from Texans. In several states with permissive abortion policies, abortion clinics are rapidly working to expand in order to accommodate the influx of out-of-state patients they expect to start receiving later this year. California will likely pass a bill this month to fund abortions and transportation for low-income women coming from out of state for pregnancy terminations. Ironically, the pro-life movement’s effort to overturn Roe v. Wade appears to be resulting in a backlash that will make it easier than ever for some women to obtain abortions – and the rapid expansion of abortion services in places such as California and New York might be enough to offset whatever small reductions in the national abortion rate would have otherwise occurred through bans on abortion in conservative states.

The other reason that “trigger laws” will have only a limited effect on abortion rates is that they apply only to surgical abortion at a time when the majority of abortions in the United States occur through abortion pills. When the Supreme Court reverses Roe, people everywhere in the United States will still be able to order abortion pills online, with an international doctor providing the prescription and an international pharmacy mailing the order. While states will no doubt try to regulate this business, it may be almost impossible to do so. Last September, as soon as the Texas six-week abortion ban went into effect, orders for abortion pills from Texas residents increased by 1,200 percent in a single week. And frankly, since the cost of a medication abortion is often less than half the cost of a surgical abortion – and since medication abortions are now the preferred means of terminating pregnancies in the United States – people who want to terminate a pregnancy may now have every incentive to choose the abortion pill.

So, for pro-life advocates, the initial excitement over the demise of Roe v. Wade is likely to give way to disappointment when they discover that the end of Roe does not mean the end of legal pregnancy terminations in the United States. Far fewer unborn lives will be saved than many pro-lifers imagine.

False expectation #3: The antiabortion laws passed in the wake of Roe’s demise will send women to prison if they try to terminate their pregnancies and will prompt some to resort to dangerous forms of self-abortion.

If the end of Roe is likely not to result in the benefits that pro-lifers expect, it will also not lead to the apocalyptic horrors that some reproductive rights advocates have predicted. None of the abortion “trigger laws” penalize a woman – which means that no woman can be arrested or charged for terminating her pregnancy this summer. Instead, the laws provide only for penalties on abortion providers – sometimes with draconian sentences, such as a 99-year prison term for a doctor who terminates a pregnancy. Because of that, these laws will have the immediate effect of shuttering every remaining abortion clinic in their states. But once the abortion clinics are gone, word will quickly get out that abortion pills can be ordered online for less than $200 in some cases, or that private charities are helping women finance abortions in out-of-state clinics.

Indeed, it may even be true that reproductive rights advocates’ efforts to help women in restrictive states access abortion services might make abortion easier to obtain for many women than it is today. Right now, a woman in Missouri who wants to terminate her pregnancy has to go through a 72-hour waiting period to access services at the state’s only abortion clinic where, of course, they have to pay for the abortion themselves. Once that clinic is closed, women in Missouri may well decide that traveling to one of the several clinics that exist in the East St. Louis, Illinois, suburbs, where there is no required waiting period, is an improvement over the existing situation in their state.

But will restrictive abortion laws passed during the next year penalize women? This year, several such bills were proposed. Missouri considered a bill to ban women from traveling out of state for an abortion. Some abortion opponents calling themselves “abolitionists” have called for women to be punished for terminating their pregnancies, but the mainstream pro-life movement has always resisted this.

Right now, I am aware of only one state policy that could be used in a post-Roe era to penalize women for having an abortion: Georgia’s heartbeat bill. This law, which was struck down by a court in 2019, will not go into immediate effect after Roe v. Wade is overturned, but it may be reinstated a short time later, after a court challenge. While most antiabortion legislation specifically prohibits a physician or other person from performing an abortion – and many of these laws specifically exempt a woman who obtains an abortion from being prosecuted for the action – Georgia’s heartbeat bill does not contain such language. Instead, it defines a 6-week-old embryo or fetus as a human life, thus allowing the state to treat an abortion performed anytime after that point as murder. Some legal experts, therefore, believe that the law could be used to sentence a woman to life in prison if she takes abortion pills or obtains a surgical abortion. Whether this would really happen is unknown, since the law is vague on this point and open to competing interpretations. It is a possibility – though one might imagine that the political outcry from the majority of Georgia voters in a state that is almost evenly divided between Republican and Democratic voters would be enough to deter the state government from enforcing this poorly written law in the draconian fashion that some reproductive rights advocates have warned.

In any case, we can safely say at this point that the vast majority of restrictive abortion laws – and all of the abortion laws that will go into effect this summer – exempt women from being prosecuted for their abortions. There will be no police investigation of women’s miscarriages or suspected pregnancy terminations. Women will not be sent to prison for having an abortion. If this changes in the future, it will only be because state governments choose to embark on a new path that the laws that will take effect this summer will not permit. And right now, the nation’s leading pro-life organizations are opposed to any change that would allow the prosecution of women for their own abortions.

As long as women are not prosecuted for self-abortions – and as long as abortion pills are readily available online and subsidized surgical abortions are available in other states – I think it is highly unlikely that the number of women choosing dangerous forms of self-abortion will be any higher than it is today. For the majority of women in the United States, legal abortion will continue to be just as affordable and accessible as it is today. Even in highly restrictive states, the opportunity to get subsidized abortions in California, low-cost abortion pills online, or a surgical abortion in a neighboring state without a mandatory waiting period is likely to deter most women from resorting to a coat-hanger or a “back-alley butcher.” It is certainly true that it will not be as easy for a woman in Houston or Dallas to get an abortion as it would be for a woman in Los Angeles. But it’s not as easy for a woman in Houston or Dallas to get an abortion even today – and it hasn’t been for years. The end of Roe v. Wade will not result in an era of the “Handmaid’s Tale.” It will instead simply perpetuate and exacerbate the situation that already exists today.

False expectation #4: The reversal of Roe v. Wade will lead to a backlash against Republicans that will benefit Democrats in the 2022 midterm elections and beyond.

While Republicans may suffer for this in a few swing states, current polling suggests that in most areas of the country, Republican incumbents will not face a backlash from voters for their party’s actions on abortion. In Texas, for instance, Republican governor Greg Abbott is currently polling ten percentage points ahead of his Democratic challenger, Beto O’Rourke. In Georgia, Brian Kemp is polling ahead of his Democratic challenger, Stacey Abrams. And in all of the “trigger law” states that are set to ban abortion this summer, Republicans are so deeply ensconced in power that it’s difficult to imagine a Democratic upset under any conditions.

The reason why the end of Roe is not likely to result in the anti-Republican backlash that some Democrats anticipate is that nearly every state policy on abortion that is likely to be enacted after Roe conforms very closely to existing abortion policy in that state. The states that will likely ban abortion in the near future are the states that already have very few abortion clinics and very low abortion rates. Conservative states with larger numbers of abortion clinics (such as Florida) are not scheduled to ban abortion this year. (Florida’s 15-week ban hardly counts as a substantive prohibition, since it will affect at most only 7 percent of the abortions that are currently performed in the state, and since it is highly unlikely to lead to the closure of even a single abortion clinic).

False expectation #5: The reversal of Roe v. Wade will move the country closer to a national ban on abortion.

If a national ban on abortion is ever passed, it will only be in a political climate that is currently unimaginable. The reversal of Roe will do little more than ratify what has already been apparent to many observers for a long time: The country is deeply divided on abortion, and that divide now falls largely on partisan lines that reflect deep regional polarizations. As long as that division continues – and it shows no signs of abating – a national abortion ban will be impossible to implement or sustain. Even the Republican Party has shown only limited interest in such a ban. Many northeastern Republican politicians and others serving in states that have strong traditions of abortion access are not eager to see any additional abortion restrictions in their region.

So, the end of Roe v. Wade will serve as a long-term acknowledgement that we as a country have not been able to agree on abortion. The pro-life movement has not been able to get a national legal declaration that human life must be protected from the moment of conception. It probably won’t be able to get that sort of declaration even from a number of Republican states. And the reproductive rights movement has failed in its attempt to preserve a national constitutional declaration that affirms abortion rights. We will therefore have to settle for a non-settlement of the issue – a non-settlement that affirms that abortion cannot be considered a constitutional right, but neither can the right to life for the unborn.

Perhaps, in the end, what will be most frustrating for many Americans after the demise of Roe v. Wade is the lack of change resulting from this development. There will be no wave of unborn lives saved, no mass cultural shift toward the pro-life (or pro-choice) side, and no major backlash against the Republicans. After the initial euphoria of passing antiabortion legislation in a number of conservative states subsides, pro-lifers will be frustrated to find that those laws prevent very few women from accessing legal abortion. And after the dire warnings about the coming subjugation of women, reproductive rights advocates will find that the Supreme Court’s direct effect on most women’s lives is so slight that it’s impossible to use this moment to generate the mass enthusiasm for a women’s rights movement to challenge the conservatives. Both sides will continue the fight, but with more confusion than ever as they realize that what they really wanted is not something that the Supreme Court can provide. That’s because when the Supreme Court reverses Roe v. Wade, it will not be offering a grand solution to an intractable problem but rather reaffirming the status quo of cultural division. If we’re surprised by that outcome, maybe it’s because we’ve forgotten how deep the regional divisions on abortion already were in the United States.