“So, what are you working on right now?

“I’m doing a book called Storm of Images. It’s about Byzantine Iconoclasm”

“Um, seriously? Why?”

Well, that wasn’t the ideal reaction I expected from a friend at my church, but it did raise an interesting point about how I explain what I am doing. I am currently writing a book – under contract to Baylor University Press – which in my view, deals with some of the most important issues in the history of Christianity, and of religion more generally. But maybe it’s the technical label of iconoclasm, maybe it’s that people find the “Byzantine” obscure and off-putting. So why am I doing this?

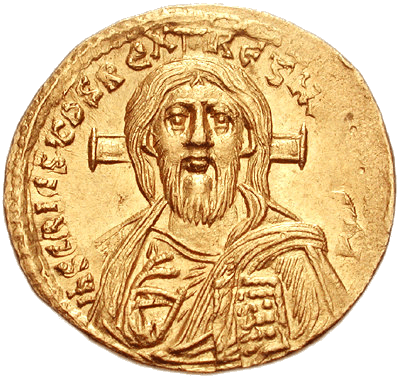

Between about 720 and 850, the East Roman (Byzantine) world was the subject of a fierce struggle over the legitimacy of images in religious contexts – of all sorts of depictions in any media, and not just “icons.” In some cases, sacred images were destroyed in churches, torn down or smashed: iconoclasm just means “image breaking.”

During the most intense stages of the struggle, many individuals were persecuted, tortured, or killed in the cause, cities and families were bitterly divided, and religious houses ruined or uprooted. The implications for wider Christian history were far-reaching, involving as they did such themes as the role of the senses in worship, the representation of holiness in material form, and the distinction between legitimate devotion and impermissible superstition. In cultural terms, the struggle was crucial for relations between East and West – between what in later centuries would respectively become the Catholic and Orthodox portions of the Christian world.

I should say here that almost every detail of this whole controversy is subject to extreme debate over the reliability of sources, far more than in most historical debates, and I pay full attention to those often technical questions. But for the present argument, let me pass over that issue.

Obviously I have vastly more to say about this whole crisis, but here let me focus on a couple of key points that I think are particularly important.

The first, probably, is how this epoch fits into the whole trajectory of Christian history from Late Antiquity and into the Middle Ages. I had already discussed these eras in two related books, in my The Lost History of Christianity (2008) and my Jesus Wars (2010), the latter of which concerned the Christological struggles of the fifth and sixth centuries. Storm of Images is very much a part of this sequence, the third volume in a trilogy. That positioning has become ever more clear as I have been writing the manuscript.

That linkage became apparent as I tried to describe the era into which the Iconoclasm issue falls, the eighth and ninth centuries. This initially seems rather late for the period of “Late Antiquity,” which is usually taken to extend from the third century through the seventh or eighth, depending on the region, and historians often date the start of the Middle Byzantine empire from 717. Having said that, one of my major themes concerns the remarkable persistence into the eighth and ninth centuries of many aspects of the religious thought and cultural world-view of much earlier eras.

That would include, for instance, the continued passion over Christological debates, which absolutely pervade the Iconoclasm controversy. Reading documents from 754, it sometimes seems as if the Council of Chalcedon happened the previous month, rather than in 451. Also recalling earlier centuries, we see the intense efforts to draw and enforce the boundaries separating Christianity from its Jewish origins. Most of the literature defending images grows directly out of defenses of Christian practices against Jews, mainly in the seventh century, and particularly on issues of idolatry. Um, didn’t Christians get all this figured out back before 200?

I also found startling the role in the iconoclasm debates of Christian heretical movements like the Paulicians, whose ideas sound as if they should have belonged to the second century, not the eighth. And then there is the continuing fascination with charismatic and prophetic holy individuals, who (again) look as if they should have belonged to 300 AD, not 800. I have no hesitation in assigning the Iconoclasm debate to “Late Antiquity,” and it very much continues debates that we might have thought to have been long extinct by that point.

The Iconoclasm debate also looks forward, sometimes amazingly so. When we think of Christianity in the Early Middle Ages (and much later), we all too easily think of simplistic superstition, and the rigid suppression of any alternative approaches by the allied forces of church and state. We might even suppose, condescendingly, that those bygone societies simply did not have the intellectual capacities to evolve “higher” and less superstitious forms of faith, which only became possible after the Renaissance. Such ideas, we might assume, were simply not thinkable before those more enlightened ages.

But then, with considerable surprise, we turn to the world of the iconoclasts, who rejected so many aspects of what became the Catholic or Orthodox world view. In the 760s, the Iconoclastic emperor Constantine V and his allies envisaged a world free of monasteries and the despised Black Robes who inhabited them, those men and women who wore what the emperor termed the garb of darkness.

It is easy to list analogies to the European Reformation of 750 years later. If we take the surviving accounts of Constantine’s policies at face value (and all of the statements are controversial to some degree), these resemblances would include not just the demolition or removal of images, including some claimed to have supernatural origins, but also a vigorous campaign against monasticism; the secularization of monastic houses and lands, which were instead given to the emperor’s military followers; an attack on monastic celibacy; forcing monks and nuns into the secular life; the confiscation of church treasures; the removal or destruction of saintly relics, and a rejection of the cult of relics as such; the prohibition of lay individuals wearing sacred images or tokens; and the severe persecution of monks or clerics who protested the violation of their familiar ways. Don’t ever tell me that nobody thought such things in the “superstitious” environment of the Middle Ages. Oh yes, they did.

Knowing about Iconoclasm cannot fail to rewrite what we think we know about the trajectories of Christian history, both before and after this spectacular conflict.

More next time.