In 1970 John Perkins had an idea. Six years earlier Freedom Summer had attracted civil rights activists to the South, and it had moved the needle. There had been freedom protests, freedom schools, freedom housing, freedom libraries, and a drive to register African Americans to vote. To be sure, it hadn’t been easy. Over 1,000 people had been arrested, eighty workers beaten, thirty-seven churches bombed, four white workers killed, and at least three African Americans murdered. Despite—or perhaps because of—the terrible violence, President Lyndon Johnson later that summer signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Wouldn’t it be great, thought Perkins, if evangelicals could accomplish their own civil rights victory?

But “Freedom Summer 1971” was a disaster. Perkins, the founder of Voice of Calvary, an evangelistic and social service ministry in Jackson, Mississippi, brought together members of the black student association at the University of Michigan and white fundamentalist youths from California for a three-month period of intense community-building. As scholar Charles Marsh describes it, the white participants came armed with Campus Crusade’s “Four Spiritual Laws” booklet; many of the black participants had just read Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver. Not surprisingly, cultural misunderstandings and resentments mounted as the summer progressed. Half of the Black students ended up “bunkered down in the Jackson headquarters of the Republic of New Africa, sparring with local police and the FBI in a gun battle.” The fearful white students could hardly bring themselves to step outside the community center. At the beginning, Perkins had said, “This summer will be great. . . What a combination: black and white, socially oriented and spiritually oriented. All with skills and energy!” At the end, he called it “the biggest failure in Voice of Calvary history.”

This social experiment was not an isolated case of racial tension. At the 1973 Thanksgiving Workshops of the evangelical left, for example, many black participants were at first “deeply encouraged” to find whites of “like precious faith” willing to sign a statement that confessed “the conspicuous responsibility of the evangelical community for perpetuating the personal attitudes and institutional structures that have divided the body of Christ along color lines.” White delegates also seemed responsive to a laundry list of proposals from a hastily formed Black caucus. But that hope receded. At the 1974 Workshop, Black participants convened a caucus to ensure “substantive” consideration of their proposals, but the 1975 Workshop, which only addressed theoretical models of social concern, did precisely the opposite. After listening to long presentations on Anabaptist, Lutheran, and Reformed political theory, Bentley rose to “shatter the calm, analytical atmosphere,” declaring, “I question whether you people can even see us blacks.”

Most Black evangelicals had not begun with these critiques. As late as 1969 they expressed ambivalence toward Stokely Carmichael, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other advocates of Black Power. On one hand, they agreed that American society was structurally racist and saw need for some independent black institutions. On the other hand, they criticized what they saw as the excesses of the movement, specifically the new openness to violence among SNCC members and a more strident black separatism emerging in some quarters. They still sought to fulfill Martin Luther King, Jr.’s vision of “beloved community.”

But beloved community did not feel so beloved when they experienced white evangelical versions of it, and their skepticism of Black Power rapidly dissolved. Young black evangelical students, incensed by discrimination at evangelical colleges, appeared in John Alexander’s magazine Freedom Now posing with a black power salute. In an extended interview, these “black militant evangelicals,” as the magazine’s editor called them, insisted on the creation of separate black institutions. White institutions were irrelevant, one explained, and white educational institutions created for blacks were inferior and failed to use black symbols to teach children. Another asserted, “What we need is a black, fundamental, Bible-believing, Bible institute and college that will dehonkify our minds and teach us how to communicate Christ to black people.” The impulse by early Black leaders like missionary Howard Jones to create an integrated evangelical community lost momentum as a younger generation embraced racial separatism.

Disillusioned with the mainstream evangelicalism and dismayed by the lack of cultural cohesiveness among black youth, these young Black leaders unleashed a torrent of critiques. In Your God Is Too White, Columbus Salley wrote, “Black Power begins with the realization that blacks have been conditioned by white institutions to hate themselves and to question their basic worth,” wrote. Evangelicalism had conditioned blacks to believe in a “white, blue-eyed Jesus—a Jesus who negates the humanity of their blackness, a Jesus who demands that they whiten their souls in order to save them.” Ron Potter called for the “theological decolonization of minds,” mourning that black evangelicals still “see through a glass whitely.”

Disillusioned with the mainstream evangelicalism and dismayed by the lack of cultural cohesiveness among black youth, these young Black leaders unleashed a torrent of critiques. In Your God Is Too White, Columbus Salley wrote, “Black Power begins with the realization that blacks have been conditioned by white institutions to hate themselves and to question their basic worth,” wrote. Evangelicalism had conditioned blacks to believe in a “white, blue-eyed Jesus—a Jesus who negates the humanity of their blackness, a Jesus who demands that they whiten their souls in order to save them.” Ron Potter called for the “theological decolonization of minds,” mourning that black evangelicals still “see through a glass whitely.”

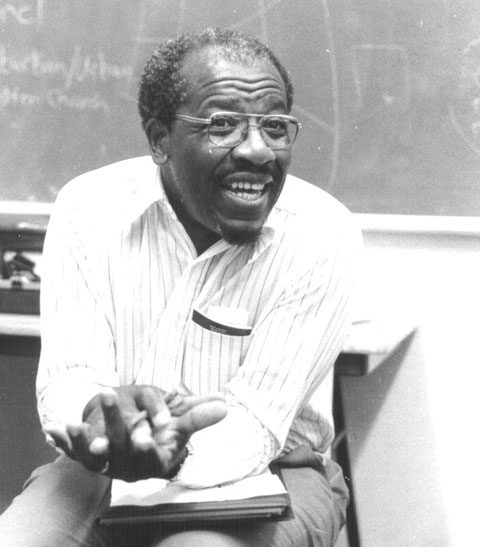

William Bentley, dubbed the “godfather” of militant black evangelicals, proclaimed a “Declaration of Independence from uncritical dependence upon white evangelical theologians who would attempt to tell us what the content of our efforts at liberation should be.” He called instead for an authentic Black evangelical theology, one that was biblical, grounded in “concrete sociopolitical realities,” and that did not “merely blackenize the theologies of E.J. Carnell, Carl F. H. Henry, Francis Schaeffer, and other White Evangelical ‘saints.’” While such thinkers could offer some insight, Bentley acknowledged, too many young Black evangelicals were “under the academic spell” of white evangelical intellectuals who suffered from “blindness to the specifics of the Black American experience.” Rather, Salley insisted, “God must become black.” Clarence Hilliard, co-pastor of the interracial Circle Church in Chicago, echoed, “Jesus stood with and for the poor and oppressed and disinherited. He came for the sick and needy. … He came into the world as the ultimate ‘n—–’ of the universe.” Black evangelical theology, wrote Bentley and Potter, should build on an “ethnic brand” and draw from black sources such as James Cone and the collective experience of Black evangelicals.

Calls for the creation of a Black theology grew into a broader push for racial identity and “ethnic self-acceptance.” Since black culture “has been lost, stolen, or destroyed,” wrote Walter McCray, noted author and founder of Black Light Fellowship in Chicago, “syncretism and integration must be checked. We must, as best we can, isolate what is our own culture.” McCray, who discouraged interracial dating, encouraged black students to “read and ponder on Blackness. Students must be ever learning about themselves as Blacks.” Wyn Wright Potter, staff member of the Douglass-Tubman Christian Center in the Robert Taylor housing project in Chicago, told white participants at a conference on politics at Calvin College in 1974 about how “Jesus Christ the Liberator” heals the wounds of black America by “fostering black identity and human dignity.” In order to heal their psyches, they needed to be part of an all-encompassing Black community, and whites needed to stay out of the way. “Whatever role whites play in a leadership capacity,” explained Bentley, “it should be of an indirect nature and complementary to, not in advance of indigenous Black leadership.” Before racial integration could occur within evangelicalism, individuals needed psychological wholeness rooted in ethnic consciousness.

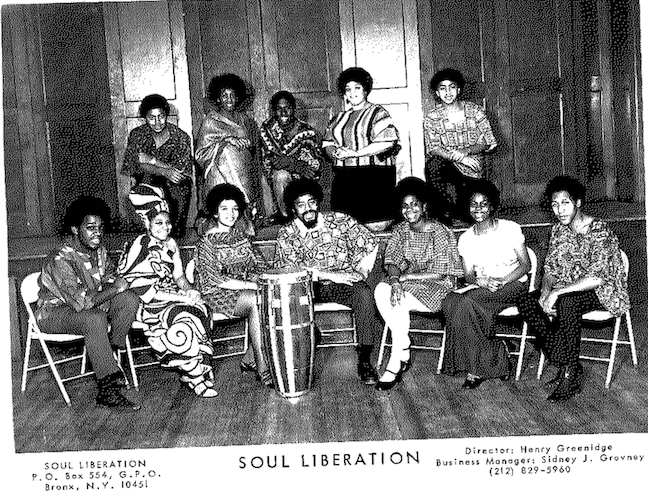

Indeed, as white evangelical energy on issues of race waned in the late 1970s, Black evangelicals began to focus their own energy into dozens of Black organizations. Many were affiliated with the National Black Evangelical Association, which built local chapters in Portland, Chicago, New York City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Seattle, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Detroit. By 1980, it had a mailing list of five thousand and claimed an “extended constituency” of thirty to forty thousand. These were microscopic numbers compared to the total number of fifteen million Protestant, church-going African Americans. They were significant, however, within the lily-white neo-evangelical orbit.

Did this new emphasis on Black identity exacerbate the already wide cultural divide and contribute to the deterioration of black-white cooperation? Perhaps. But the more salient narrative is that beloved community was a fiction in the first place. Again, how beloved could it really be given neo-evangelicalism’s white structure, given its proclamations of colorblindness even as it privileged white voices and dominated institutions?

Since the 1980s a new wave of biblical hermeneutics—much of it produced by Black, Hispanic, and global scholars—has been offering new ways of thinking about Christian community. It speaks of the Apostle John’s vision of an evangelical future that is decidedly not colorblind. It speaks of “a new heaven and a new earth” after “the first earth had passed away,” of a “Holy City, a new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God.” The new contextual work notes that Jerusalem in that era was a large capital city of about a quarter of a million people. It was a cosmopolitan city, one teeming with the exotica of the ancient world: disciplined Roman legions, Greek travelers, merchants from Asia, and of course the many varieties of Jews. If Jerusalem was the basis of John’s vision, the promised land will be a place of vibrant multiculturalism. “I heard a loud voice from the throne,” John exulted in Revelation 21. “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God.”

These words offer an eschatological vision with color and with shape. It is not a monocultural vision of a melting pot in which everyone acts the same, dresses the same, speaks the same language, and integrates into a white, middle-class American mainstream. It’s a diverse collection of sojourners who have created, perhaps uncomfortably but certainly meaningfully, a home together.

In my experience this eschatological vision continues to be more of a vision than a reality. But perhaps the theological creativity and Black identity that has risen out of the ashes of Freedom Summer and the travails of the 1970s is making a difference. Perhaps beloved community will paradoxically materialize out of separation.