I am delighted to welcome Sam Young back to the Anxious Bench for more of his fascinating research on Luther’s complicated legacy for American women. If you missed his first post, check it out here.

As I explored in my previous post, identifying Luther as a liberator of women was hardly an oddity in antebellum America. Often Americans meant liberating from the forced celibacy of the convent into what they thought of as their proper sphere as mother and wife. But appreciations of the reformer could go beyond an exaltation of the domestic sphere, broadening to include appeals for women’s political rights. Luther’s last will and testament became a salient historical fact for these activists, confirming that the reformer—in leaving all his property to his wife—supported woman’s political rights and property ownership. Not all woman’s rights proponents were convinced, however, and disagreement over the meaning of Luther’s will accompanied competing interpretations of the reformer’s import for the woman’s rights movement.

By the 1850s, supporters of women’s rights often made the link between their cause and the Protestant Reformation. Speakers at woman’s rights conventions compared their labors to the efforts of Luther, with American women picking up the reformer’s mantle to extend liberty to all of humanity. The metaphor was a favorite of prolific abolitionist and woman’s rights advocate Wendell Phillips, but was echoed by others. Activist Sarah Wall, defending an 1858 petition to the Massachusetts Legislature for woman’s equal rights, likened the subjugation of women to the oppression that Luther endured as a cloistered monk. Wall argued that, like Luther, American women were becoming aware of their deprivation, and desire for equality was the end result (40).

In arguments for increasing the legal rights of American women, Luther’s last will and testament became a noteworthy witness to the reformer’s support for the same cause. In the text, Luther commends his wife as a pious and faithful spouse. To show his faith in her, and to prevent squabbling among his children, he gave all of his possessions to Katharina. The text of the will, included in early nineteenth-century edited volumes of the reformer’s German works, was published in English translation in the late 1830s and early 1840s.

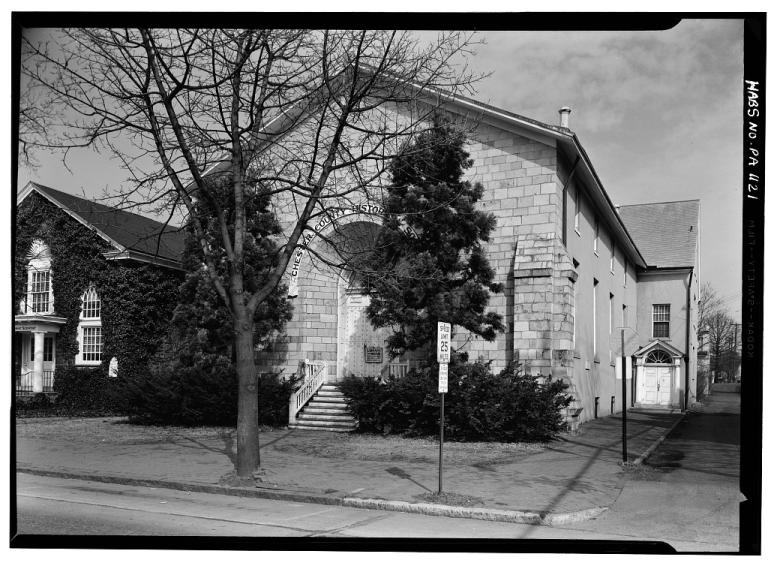

Some in the woman’s rights movement interpreted Luther’s will as conclusive evidence that the reformer supported women’s equality and would support American legal reforms if alive in the nineteenth century. Joseph A. Dugdale, a Quaker activist, made a speech to this effect during the 1852 Woman’s Rights Convention held just outside of Philadelphia in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The published summary of the speech noted that Dugdale began with a description of the unjust laws governing inheritance after the death of a husband and father. While the goal remained to change those laws, Dugdale urged men to write their own wills explicitly “conveying the whole property of their joint industry and economy to the wife, in the event of his death.” To prove the wisdom and justice of this action, Dugdale read extracts from Luther’s will. Such an attention to the well being and rights of his wife proved “that other errors than those of the Church, were deemed by the great reformer of sufficient magnitude to awaken his earnest opposition.” For Dugdale, Luther’s will was the smoking gun confirming the reformer’s support for the expansion of legal rights for women.

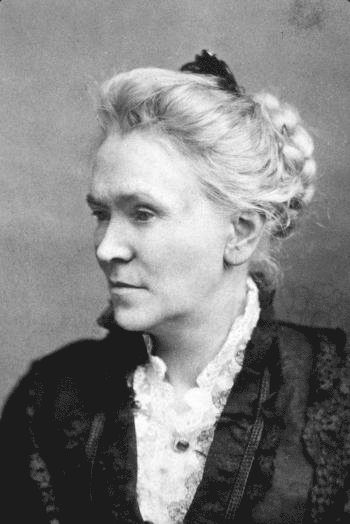

Dugdale’s assertions would not go unchallenged, however, and the opposition he received at the West Chester meeting illustrates a broader disagreement among woman’s rights leaders about the wisdom of invoking Luther for their cause. After Dugdale’s speech, Lucretia Mott, the Quaker and early woman’s rights activist, rose to challenge the tone of the previous speaker. Mott argued that women deserved greater sympathy for their plight. The fault did not lay in woman “in herself” or in “her inferior condition” but in the unjust systems and laws in which “she has had no voice.” It would take more than just benevolent husbands to change this system. If women—as the “oppressed”—would “cry for deliverance,” then the “wrong-doer and oppressor” could be acknowledged and reform achieved.

Mott’s frustration over Dugdale’s concentration on the duties of virtuous husbands towards their wives led her to criticize his exaltation of Luther as a woman’s rights activist. The reformer’s last will and testament, Mott granted, gave “evidence of the appreciation of the services of his wife” and displayed a “generous disposition to reward her as a faithful wife.” However, Mott argued that the document proved “the degrading relation she bore to her husband.” Rather than supporting contemporary estate law reform, Luther’s will only reinforced patriarchal relations between the sexes. Katharina was not owed her husband’s property, but was dependent on his generosity. Mott argued that in the will, there was “no recognition” of Katharina’s “equal right to their joint earnings.” While a woman might have been “obliged” to accept these gifts from a generous husband when he died, it still reinforced the notion that she was merely an “inferior dependent,” rather than an equal partner.

For Mott, the elevating of Luther as a champion for woman’s rights actually exacerbated the problem. Celebrating these virtuous men from history obscured the ways in which a society’s laws and customs reinforced female inferiority. Emphasizing benevolent husbands like Luther did not address these oppressive systems, and did more harm than good for woman’s rights.

Feminist leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony documented the disagreement between Dugdale and Mott in volume one of their History of Woman Suffrage. The debate over Luther’s will presaged further ambiguity among woman’s rights leaders about the ways in which their movement could claim Luther’s Reformation heritage. In their periodical The Revolution, editors Stanton and Anthony consciously invoked their movement’s relationship to the Reformation. In an 1869 piece, Stanton appealed to Luther as a champion of liberty by placing woman’s rights in the long line of movements for human equality. For her, the “present rebellion of the women” was “just as philosophical as that of Luther against the church, and the American colonies against Great Britain. The fulminations hurled at the great reformer and the fathers of ’76 seem no more absurd to us than will these stale platitudes on ‘woman’s sphere’ to the next generation” (264). In The History of Woman Suffrage, Stanton and Anthony argued that “the bold declarations of Luther” had a “marked influence in developing woman’s self-assertion.” They quoted the reformer’s views on social dynamics authoritatively, and feted leaders like Lucretia Mott as contemporary Luthers for their movement. In these ways, woman’s rights leaders leaned into the popular vision of Luther as a liberator of women, someone whose Reformation directly informed their calls for legal reform and woman’s suffrage.

But Mott’s criticisms of Luther as an agent of patriarchy endured as well. Stanton and Anthony’s co-editor of History of Woman Suffrage, Matilda Joslyn Gage, took aim at the notion of Luther as liberator of women in her 1893 Woman, Church and State. She accused the reformer of degrading women on a number of levels, marking him no better than the Catholic monks he criticized. Gage noted his support for witch hunts and polygamy; his retaining of monastic strictures in his glorification of women’s domestic duties; his constraining of women to a position of absolute dependence on their husband through a doctrine she termed “created subordination.” Despite his marriage to Katharina, the “whole course” of Luther’s life showed “that he did not believe in woman’s equality with man.” In fact, Luther showed himself to be an enemy to “woman’s intellectual freedom and independent thought.” For Gage, Luther and his Reformation had done nothing for the equality of women, and in many cases, had worsened their situation. As Stanton later stated in her provocative feminist commentary on scripture, The Woman’s Bible, “Woman was not rescued from slavery by the Reformation. Luther’s ninety-five theses, nailed upon the church door in Wittenberg, did not assert woman’s natural or religious equality with man.”

With these criticisms, Gage and Stanton took aim at one of the core claims of the American Luther myth: that his actions (and Protestantism writ large) were the basis for modern liberties. Denying him his role as “liberator of women” not only obliterated the conceptual link between the Reformation and woman’s rights, but indeed, challenged the very image of Luther as a champion for human liberty.

The confusion among nineteenth-century Americans about the relationship between Luther and contemporary gender ideals discloses the difficulties inherent to claiming complex historical figures for contemporary social or political cause. Like references to the “Founding Fathers” in American politics, the association of Luther with the expansion of human freedom makes him a particularly tempting figure to invoke in these kinds of debates.

Writing about this phenomenon in 1986, the Luther scholar Bernhard Lohse warned against the temptation to “exploit” the reformer’s legacy. Luther’s understanding of the world was thoroughly pre-modern, bounded by his sixteenth-century context. Against all efforts to mythologize and instrumentalize the reformer, the “genuine… Luther has gradually always asserted himself” (201). As Susan Karant-Nunn argues in her essay on Luther’s death, there is a real distance between modern appropriations of the reformer and his actual life and work: “Our memory of him today bears the imprint of our own values as well as of our search for reasons why our society is as it is. The features of the modern world, both good and bad, that we ascribe to him are not traceable either to his thought or to his labors in sixteenth-century Germany” (203).