Those who are righteous will be long remembered…

Their good deeds will be remembered forever.

They will have influence and honor.

Psalm 112:6b, 9b

The historical memory of Phillis Wheatley’s pronounced life has been protracted despite its brief measure of thirty-one years. Many Americans recognize who she is because she is renown as America’s first African-American poet. Beyond that, few are familiar with her poems and correspondence, let alone the story of her auspicious rise and abrupt decline. American history surveys typically pay anywhere between one sentence and one page of homage to her legacy.

The Rise of a Pilgrim of Color

A little girl of 7 years arrived in Boston aboard a slave ship called the Phillis on July 11, 1763. She had been enslaved in West Africa and survived the brutal trans-Atlantic middle passage. Upon being purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, she became a maid servant in the prominent merchant’s Boston home. The Wheatley’s had eighteen-year-old twins, Nathaniel and Mary. The daughter, Mary Wheatley, brought Phillis under her tutelage, teaching her to be an African of Letters. She learned English within eighteen months and advanced in the coming years to learn history, Sacred Writings, Classical Literature, and some Latin.

She likely heard George Whitefield preach at Old South Church during his last preaching tour of America in 1770. Even if not, we know certainly that Samuel Cooper baptized her in this church on August 18, 1771, and prior to baptism, in the later part of 1770, Phillis wrote a beautiful elegy of the Great Awakening revivalist, Whitefield, which was published in both Boston and London newspapers shortly after his death. Wheatley sent a letter to Selena Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, dated Oct 25, 1770, which enclosed a hand-drafted copy of her elegy of Whitefield, who was the Countess’s chaplain. The successful publication of her poetic elegy of Whitefield, the letter to the Countess, and later correspondence prompted the Countess to invite Phillis to England and sponsor a printed collection of her poems.

Accompanied by her mistress, Susanna, and her young master, Nathaniel, Phillis arrived in London and met Lords, Ladies, and other elite. She was introduced to a sophisticate and genteel society. In July of 1772, a year prior to her visit, Lord Mansfield ruled in favor of an African slave from Boston, James Sommerset, on a case that set a precedent for all slaves who sojourned to England. The ruling, popularly known today as the Sommerset Decision, protected slaves from being forced to return to their land of enslavement once they reached freedom’s shore in England. Some speculate that John and Susanna Wheatley convinced Phillis to voluntarily return to New England on the condition that they would free her shortly after her return. Regardless of what motivated her voluntary return to Boston, she did indeed return, and her masters manumitted her shortly thereafter.

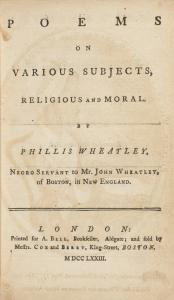

Poems on Various Subject, Religious and Moral was published in 1773 from London. Over 300 copies were transported to New England and sold by Cox and Berry in Boston. Advertisements for subscriptions appeared in the Boston Censor, the Massachusetts Gazette, and the Boston News-Letter during 1772 and 1773. Wheatley’s first and only publication could be reserved at a subscription price that ranged from two to four shillings, depending on the bookseller, quality of paper, the type, and the binding of the text. The solitary likeliness we have of Phillis is due to the Countess’s insistence that a frontispiece of Phillis ought to be commissioned. This likeness of Phillis appeared in the first and subsequent printings of her volume of poetry. Poems on Various Subjects was 86 pages in length and included 39 original pieces of poetry.

Poems on Various Subject, Religious and Moral was published in 1773 from London. Over 300 copies were transported to New England and sold by Cox and Berry in Boston. Advertisements for subscriptions appeared in the Boston Censor, the Massachusetts Gazette, and the Boston News-Letter during 1772 and 1773. Wheatley’s first and only publication could be reserved at a subscription price that ranged from two to four shillings, depending on the bookseller, quality of paper, the type, and the binding of the text. The solitary likeliness we have of Phillis is due to the Countess’s insistence that a frontispiece of Phillis ought to be commissioned. This likeness of Phillis appeared in the first and subsequent printings of her volume of poetry. Poems on Various Subjects was 86 pages in length and included 39 original pieces of poetry.

Besides her elegy to Whitefield, other noteworthy poems included her first poem penned at age 15 “To the University of Cambridge, in New England” (a poem of encouragement to Harvard University students), “To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty. 1768” (a poem to George III, after he revoked the Stamp Act), “Goliath of Gath” (a poetic recount of David slaying Goliath), and “Niobe in Distress for her children slain by Apollo” (a poem derived from Ovid’s epic Metamorphoses).

Wheatley’s poems were preceded with an endorsement from a council of leading Bostonian men. Eighteen ministerial, intellectual, and political leaders met with Phillis and judged her rational and artistic capacity to produce poetry. Among this council were seven ordained ministers, three poets, six future loyalists, and several future revolutionaries. Almost all were Harvard graduates. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. describes this meeting as a trial and asserts, “Their interrogation of this witness, and her answers, would determine not only this woman’s fate but the subsequent direction of the antislavery movement, as well as the birth of what a later commentator would call ‘a new species of literature,’ the literature written by slaves” (Gates, The Trials of Phillis Wheatley, 7). The countess’s patronage as well as the Bostonian literati’s endorsement influenced the short-term course of Phillis Wheatley’s New England life, launching her into the public eye as an artist, gentlewoman, and celebrity.

By 1773, a decade after her enslavement, Phillis had become a literate intellectual, the first published African-American woman, and a person who fluidly moved among the transatlantic elite of London and Boston society. After her manumission, she continued to compose new pieces of poetry and participate in the “Republic of Letters.”

The Philosophical Genius of a Pilgrim of Color

Her letter to the Mohegan minister, Samson Occom, dated February 11, 1774 reveals her piercing convictions concerning chattel slavery, abolition, and insight to her subtle philosophic brilliance. She writes:

Her letter to the Mohegan minister, Samson Occom, dated February 11, 1774 reveals her piercing convictions concerning chattel slavery, abolition, and insight to her subtle philosophic brilliance. She writes:

Rev’d and honor’d Sir, I have this Day received your obliging kind Epistle, and am greatly satisfied with your Reasons respecting the Negroes, and think highly reasonable what you offer in Vindication of their natural Rights: Those that invade them cannot be insensible that the divine Light is chasing away the thick Darkness which broods over the Land of Africa; and the Chaos which has reign’d so long, is converting into beautiful Order, and reveals more and more clearly the glorious Dispensation of civile and religious Liberty, which are so inseparably united, that there is little or no Enjoyment of one without the other: Otherwise, perhaps, the Israelites had been less solicitous for their Freedom from Egyptian Slavery; I don’t say they would have been contented without it, by no Means, for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverence; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert that the same Principle lives in us. God grant Deliverance in his own Way and Time, and get him honor upon all those whose Avarice impels them to countenance and help forward the Calamities of their fellow Creatures. This I desire not for their Hurt, but to convince them of the strange Absurdity of their Conduct whose Words and Actions are so diametrically opposite. How well the cry for Liberty, and the reverse Disposition for the exercise of oppressive Power over others agree,—I humbly think it does not require the Penetrations of a Philosopher to determine. (Ed. by Carter et all, Documentary History of Religion in America, 100)

Two observations concerning this letter are noteworthy for comprehending the philosophical genius of Phillis Wheatley. First, it appears, if nothing else than in semantics, she was fluent in the language of the New Divinity movement, a language with which Samson Occom was quite conversant. The New Divinity movement and New England Theology was Jonathan Edwards’s theological legacy. If Wheatley had not read Edwards, then she had minimally been immersed and saturated in a cultural community fluent in the discourse of the New Divinity movement, and she appears to be an avid participant in this discourse.

Second, perhaps, as a result, her profession that the principle of liberty had been implanted in every human breast was a nod to both Locke and Edwards. While Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding overturned the idea of innate ideas implanted in the human mind by a divine being, Edwards followed an Augustan tradition that adopted the will as the control center for the soul. Wheatley professed her loyalty to this voluntarist tradition and indicated that the human impulse or habit was to cry for liberty. If Locke’s assertion that God does not indeed incept ideas into the intellect, the Lord may still implant them in the affections. One might even speculate that the notion of implantation subverts Newtonian mechanics and hints toward adopting Friedrich Christoph Oetinger’s organic system, which united biblical revelation with history and nature (W. R. Ward, Early Evangelicalism, 158–60).

The subtlety and brilliance of this single line from Wheatley’s letter tell us much about how well she fits into the classical tradition of both a poet and a philosopher, despite her cheeky conclusion that these insights do not require “the penetrations of a philosopher.” Bruce Hindmarsh makes similar observations concerning Wheatley’s acumen with scientific and philosophical reflection, including her affinity for the voluntarist tradition, in her poem, “Thoughts on the Works of Providence” (Bruce Hindmarsh, The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism, 160–63).

Finding a Match to the Prestige of a Pilgrim of Color

In 1774, the British evangelical patron and philanthropist, John Thorton, and the Newport, Rhode Island minister, Samuel Hopkins, collaborated to convince Phillis to join John Quamino and Bristol Yamma in re-colonizing Africa. At the time, Quamino and Yamma were the first African-Americans enrolled at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), studying directly with its President, John Witherspoon. From Wheatley’s letter to politely decline this invitation, it appears she interpreted the invitation to join the re-colonizers as an attempt to find a marital match for either Quamino or Yamma. Quamino was already married. Nonetheless, the 21 year-old Wheatley considered herself ready for society, and she did indeed marry in the coming years.

In 1778, Mary Wheatley’s husband, the minister, John Lathrop, performed the nuptials between Phillis Wheatley and John Peters, a grocer. Until recently, there was scant documentary evidence for the period from 1778 and Phillis’s death in 1784. However, historian Cornelia Dayton recently recovered much of the mystery of this story when she found 120 documents (called the Middleton Dosier) related to litigation involving John Peters. The newly married Phillis Wheatley Peters moved with her husband John to settle at the Wilkins Estate in the village of Middleton, Massachusetts. Middleton had annexed from the western part of Salem Village (now Danvers) in 1728. Its elite included Major Ezra Putnam, one of the scions of the notorious Putnam family, who were implicated in the Salem Witch trials of 1692. Lieutenant John Wilkins, having no immediate sons or other male heirs, left a bequest to Peters and gave him influence over the probate of the estate in his will. Wilkins’s widow, Naomi, deeded the home and 100 acres of the estate to John, in order to convince him to settle on the estate, manage the farm, and care for her in her late age.

John Peters was no mere grocer. The documentary evidence reveals that he was a savvy merchant and barrister, who managed his own business and legal affairs, as well as the Wilkins’s farm for years. During the Middleton period of Phillis’s life, she and her husband arrived at a rank in society akin to John and Susanna Wheatley, Phillis’s masters in Boston. For Phillis, this had likely been her longing since her manumission. While in the Wheatley home, Phillis had been a daughter to them. In fact, her arrival in their home came on the 9-year memorial of their loss of Sarah Wheatley, who passed at 7 years-of-age. Around the time Sarah would have entered into society, Susanna found a surrogate 7 year-old daughter, Phillis, to raise. Now she had arrived at the station and rank fitting for a Wheatley daughter. Cornelia Dayton develops a portrait for why Phillis’s affections were drawn to Peters: “John Peters’s wide range of skills, resourcefulness, legal literacy, mien of manly gravitas, and fierce defense of his rights are very much in evidence; these suggest some of the reasons Phillis Wheatley married him” (Cornelia H. Dayton, “Lost Years Recovered: John Peters and Phillis Wheatley Peters in Middleton,” The New England Quarterly, 94, No. 3 [Sep. 2021]: 312).

The Regress of Righteous Pilgrims of Color

Unfortunately, the rest of Middleton did not wish to condescend to the rank of the black Peters couple, who were maintaining the Wilkins Estate until it became the Peters Estate. The Putnams, Esteys, and other white elite Middleton families colluded with Naomi Wilkins’s nephews to legally wrest the estate from John Peters. Benjamin Wilkins, Jr. received legal control to manage the Wilkins’s farm until the legal dispute between John Peters and the Wilkins’s was settled.

The Peters were forced to remove to the West End of Boston in the summer of 1783, liquidating fine furnishings, Phillis’s books, and other symbols of status in society, in order to cover mounting legal expenses. Travel back and forth from Boston to Middleton and other legal expenses left the Peters couple destitute and put John into debtors prison.

During the Middleton period, Phillis had at least one miscarriage and likely loss a 2-year old child. While pregnant with another child, she worked as a scullery maid and advertised in Boston newspapers, in an effort to acquire the necessary subscriptions to put a second volume of her poetry to print. She gave birth to a newborn infant, and subsequently died from an infection contracted after the birth. Her infant perished in her arms during one of the coldest winters on record in New England. John was likely given “liberty of the yard” to attend her funeral on Thursday, December 9, 1784.

Interpreting the History of a Righteous Pilgrim of Color

How does someone like Phillis Wheatley Peters go from transatlantic celebrity to destitution and anonymity? While she was a pawn in play for evangelical white knights and ladies, her life had value. Once this pawn came into her own as a black queen and found her king, the two became a threat that might up-end the chess board.

Phillis had sophisticated experiences. Provincial Middletonians had rarely been to Boston, let alone traveled to England and been in the audience of the Earl of Dartmouth. How likely would it have been for any of her Middleton neighbors to be published—let alone for the likes of Voltaire or Jefferson to have read and engaged the publication? What would it have been like for a Middletonian to sit in the parlor room of the Peters, sense their fine furnishings and library, feel a copy of Phillis’s Poems on Various Subject, Religious and Moral, and perceive their blackness?

The station and rank of the black Peters agitated their white supremacist neighbors enough to drive them out of town, bankrupt them, and abandon them to despair and death. This may not simply be the anecdotal story of America’s first African-American woman poet. Rather, it’s a pilgrim history—one that very well might be an allegory of one particular righteous pilgrim’s regress in a world that has been unkind and brutal to pilgrims of color. In its own way, this pilgrim history is a similitude that portrays the long story of systemic injustice to people of color in America.