Today we welcome Daniel Montañez to the Anxious Bench. Montañez is an adjunct instructor of Christian ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and Pentecostal Theological Seminary. He is a doctoral student at the Boston University School of Theology, researching the intersection of theology, ethics, and migration. He is a co-editor of the newly released book, The Church and Migration: A Theological Vision for the People of God.

Since the rise of the Enlightenment, modern apologetics has concerned itself with giving an answer to the questions, problems, and accusations raised by skeptics of the Christian faith. Whether they be atheist, agnostic, or those of a different faith tradition, the central mission of apologetics has exhorted Christians to “Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.”[1] This mission is often traced back to the early Church, as the apostle Paul proclaimed to the Athenians that the unknown God they worshipped made Himself known in person of Jesus of Nazareth. It is also seen in early apologists such as Justin Martyr, who utilized apologetics as a means of legitimizing marginalized Christian communities within the Roman empire.[2]

Today, the context from which apologetics is done is vastly different from the early Church. One of the stark differences between apologetics then and now is that, whereas the early apologists defended their faith in a pre-Christendom context, Christians today engage the task of apologetics from a post-Christendom context. With the rise of Constantine, the passing of the Edict of Milan in 325 A.D., and the recognition of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman empire, what separates these two communities is a near 1700-year history of political turmoil, religious violence, and colonial domination that is often associated with the period of Christendom. While this narrative does not account for the significant contributions made by the Church throughout the centuries, it is nonetheless a dominant narrative that persists in our postmodern age. Therefore, any attempt to engage in apologetics today should consider Christianity’s historical context, in order to seriously and faithfully respond to the skeptics of the Christian faith of our postmodern era.

In recent years, apologists have often interpreted postmodernity as the newest threat to the Christian faith. The relativization of truth, the rise of pluralism, and the secularization of morality have all raised concerns and served as warning signals to defend pressure points upon the body of Christ. As a result, many apologists have devoted themselves to responding to ideologies such as the new atheist movement, liberal forms of ecumenism, and those that question traditional family values. While the methodology of apologists within postmodernity is consistent to how modern apologetics has responded to the ebb and flow of the cultural moment, the great flaw of contemporary Christian apologetics is that it is not self-aware. Like a bull in a China shop, the apologist often enters into the room unaware, not only of its size and within the historical narrative of Western thought, but also of the wreckage it has left behind, across marginalized cultures and communities, on its path to becoming a religious majority.

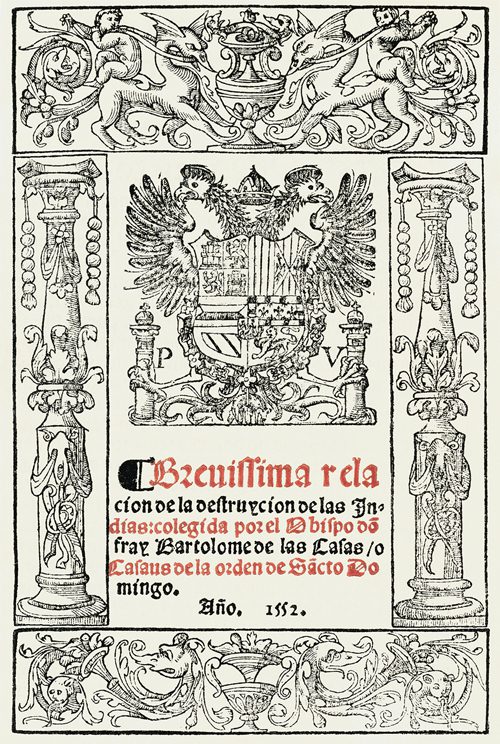

In his book, A Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas recounts his experience of witnessing Spanish rulers cut off the hands and noses of Indigenous American men, women, and children, who refused to convert to Christianity and comply with their laws. In one instance, Las Casas retold the story of “the Cacyque,[3] without any farther deliberation, told him, he had no mind to go to Heaven, for fear of meeting with such cruel and wicked Company [Christians] as they were; but would much rather choose to go to Hell, where he might be delivered from the troublesome sight of such kind of People.”[4]

The problem with contemporary Christian apologetics is that in its attempt to give a defense of the Christian faith, it lacks the understanding that it is no longer perceived as the martyr, but as the executor. No longer the victim, but the perpetrator. As the Christian apologist enters into the postmodern public square, it does so with an audience that will no longer believe in Chesterton’s assertion that, “the Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting,”[5] but instead the Christian ideal has been tried and found unwanted.

This problem is only further exacerbated by the historical baggage the American Church carries into our postmodern age, as perceived in the political crises facing evangelicalism, the resistance to social justice by many churches, and the rise and fall of evangelical leaders. The tragic revelation of renowned Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias’ sex-scandal sent shockwaves across the evangelical landscape that marked a catalytic turning point for Christian apologetics, as it challenged not only how apologetics is perceived, but also the types of questions that need answers. Today, the new skeptic of the Church in our postmodern age is no longer the atheist, but the Christian. It is the brother or sister in the faith who has been hurt or abused by the family of God and calls the Church to account for its actions. It is the one who loves the Church and calls her to repent and believe in the gospel message she preaches. Perhaps the greatest question Christianity should answer today is not whether or not it is true, but whether or not it is trustworthy. Perhaps the greatest threat to the Church is not the skeptic, but itself.

Therefore, to engage the task of apologetics in our postmodern age requires the Church to first understand how its influence and impact has shaped its societal context; the good, the bad, and the ugly. The Church does not exist within a vacuum. therefore, it should develop a proper self-awareness and sober self-understanding of how it has imprinted itself upon its surrounding cultural landscape. By doing so, it has the capacity to cultivate the interpersonal skills and sense the social ques that are necessary for practicing apologetics within a pluralistic society.

By becoming more self-aware the Christian apologist recovers the potential to regain the trust of a generation that has been hurt or abused by the Church, along with those who view the Church with deep suspicion. A key characteristic of the postmodern conscience that is often overlooked by apologists is the distrust and suspicion held towards institutions. Therefore, the apologist should seek to reposition itself from a posture that is defensive and blind to shortcomings of the institutional Church, to a position of humility that seeks forgiveness, justice, and reconciliation for those who have been negatively affected. By submitting itself to Christ the healer, the Church has the capacity to model for a watching world the true power of the message of the gospel to “repent and believe,” both for individuals and institutions.

Finally, the future of Christian apologetics must look beyond answering the questions of modernity, such as the existence of God, the historicity of Jesus, and the veracity of Scripture. These questions are the product of the Enlightenment era when the primary concerns raised against the Christian faith were related to rationalism and scientific empiricism. While these types of questions should retain a proper place in the practice of contemporary apologetics, it is important to recognize that postmodernity asks new questions. These questions include, but are not limited to:

- How do Christians account for the colonization of the Western world, the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and the enslavement of Black people, all in the name of the Christian faith?

- Is Christianity the white man’s religion?

- How should Christian leaders respond to the sex scandals, racism, and abuses of power that have left a generation of believers disenchanted with the institutional Church?

- How should Christians respond to the cries for justice among marginalized communities, rather than merely dismissing them as liberal?

- How can Christians preach a message of unity and reconciliation when the Church itself is so divided?

These are the types of questions being asked by the postmodern skeptics of our time, Christian and non-Christian alike. These questions should not be interpreted as a threat to the Christian faith, but an opportunity. They are an opportunity for the institutional Church to look more like the bride of Christ, and for the God of justice to speak into the injustices of our world today. They are an invitation to engage in an apologetic that is more concerned with “gentleness and respect” than merely “giving an answer.” They are an indication that Christian apologetics must shift its approach from having all the answers, to being present in the questions. To quote a conversation I had with Dr. Dale Coulter, “what we need are not ‘apologetic experts’ given how much expertise is being questioned, but ‘family doctors’ who live with the people and show their concern through their concrete practices.” This just may be the best defense for the Christian faith in our postmodern age.

Christians today need not fear postmodernity, for the same God that gave wisdom to the early Church and to the Christians of the modern era, is the same God that will give wisdom to the Christians of postmodern era, and for whatever future era may come.

[1] 1 Peter 3:15 (NIV)

[2] It is worth mentioning that apologetics in the early Church was vastly different to apologetics during the Enlightenment era. Nonetheless, the exhortation of Peter has been historically applied to the practice of Christian apologists throughout the centuries.

[3] An indigenous priest.

[4] Bartolomé de Las Casas, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, (Overland Park, KS: Digireads.com Publishing, 2019), 19.

[5] G. K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong with the World, (Kiribati: Cassell, 1912), 48.