I have been posting about the Bible’s genocidal texts, which have most recently been discussed in Charlie Trimm’s book The Destruction of the Canaanites: God, Genocide, and Biblical Interpretation (Eerdman’s 2022). So obvious were the flaws and dangers of these texts as to make them a gift for critics of religion in general and the Bible in particular, and fundamentalists struggled to defend them.

I particularly note one individual who undertook such a defense, as this was such a prestigious and erudite individual. I am thinking of William Foxwell Albright (1891-1971), one of the most influential figures in the archaeology of Israel/Palestine, and a chaired professor at Johns Hopkins University. He dominated his scholarly field from the 1930s through the 1960s, mentoring a whole generation of brilliant scholars, including Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman. Through works both scholarly and popular, Albright shaped how ordinary Christians in the English-speaking world understood the biblical record.

Albright was the great exponent of Biblical Archaeology, a project aimed at verifying the truth of the scripture, rather than just pursuing the academic study of a region and an era. (That approach is now held in widespread suspicion: see Thomas W. Davis, Shifting Sands: The Rise and Fall of Biblical Archaeology (Oxford University Press, 2004). Although not a strict literalist, Albright held that archaeology confirmed the textual accounts found in the Old Testament, and he believed in both the Israelite conquest of Canaan and the destruction of that region’s native societies and peoples. Albright regarded these massacres as quite justified, describing the Canaanite genocide as not just inevitable but desirable.

As he wrote, the treatment of the Canaanites was

no worse, from the humanitarian point of view, than the reciprocal massacres of Protestants and Catholics in the seventeenth century (e.g., Magdeburg, Drogheda), or than the massacre of Armenians by Turks and of Kirghiz by Russians during the First World War, or than the recent slaughter of non-combatants in Spain by both sides. It is questionable whether a strictly detached observer would consider it as bad as the starvation of helpless Germany after the armistice in 1918 or the bombing of Rotterdam in 1940.

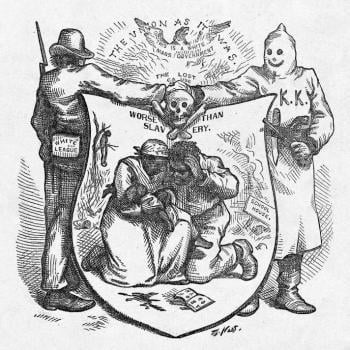

It was just as “inevitable” as the Euro-American slaughter of indigenous Indian peoples. Apparently, he regarded these analogies as a justification for the ancient massacres: everybody did it. So that’s all right, then.

Some obvious objections raise themselves. One is that he is conflating two fundamentally different kinds of action, namely brutal and indiscriminate warfare, as at Magdeburg or Rotterdam; and the conscious and deliberate genocide of every person of any and all ages, which is what God reportedly commands in the Pentateuch. This is a “War is Hell” argument that evades the basic issue of genocide. Also tendentious is his claim that such total genocide of populations was a standard custom among the various Semitic peoples, which it was not. Albright is using every piece of rhetorical sleight of hand he can muster to avoid confronting the dilemmas of the genocide texts. In so doing, he digs himself even deeper into moral quandaries.

As Albright further argued, racial replacement was part of the process of historical progress and evolution:

It often seems necessary that a people of markedly inferior type should vanish before a people of superior potentialities, since there is a point beyond which racial mixing cannot go without disaster.

Who exactly was he thinking of here? Such remarks were not uncommon for an American of his generation—he was born in 1891—and they usually referred to various tribal or “primitive” nations falling back before white domination: indigenous peoples in North and South America, Pacific Islanders, Australian Aborigines, and African Bushmen. As a committed Zionist, he was also thinking of the Arab peoples of Palestine, whose existence he scarcely acknowledged. At best, Arabs provided colorful scenery for the expanding Jewish settlements.

The irony, of course, is that in his arguments for ethnic cleansing and historical evolution, he was speaking exactly the contemporary language of the deadliest enemies of the Jews he so idolized. In 1940, he published a popular text titled From the Stone Age to Christianity, a study of the historical development of monotheism, in which he wrote,

It was fortunate for the future of monotheism that the Israelites of the conquest were a wild folk, endowed with primitive energy and ruthless will to exist, since the resulting decimation of the Canaanites prevented the complete fusion of the two kindred folk which would almost inevitably have depressed Yahwistic standards to a point where recovery was impossible. Thus the Canaanites, with their orgiastic nature-worship, their cult of fertility in the form of serpent symbols and sensuous nudity, and their gross mythology, were replaced by Israel, with its nomadic simplicity and purity of life, its lofty monotheism, and its severe code of ethics. In a not altogether dissimilar way, a millennium later, the African Canaaanites, as they still called themselves, or the Carthaginians, as we call them, with the gross Phoenician mythology which we know from Ugarit and Philo Byblius, with human sacrifices and the cult of sex, were crushed by the immensely superior Romans, whose stern code of morals and singularly elevated paganism remind us in many ways of early Israel.

How sad it is to see even the learned Albright misusing the word “decimate,” which means “to kill one in ten,” not to annihilate. Dr. Trimm does the same thing, sigh…

This frequently quoted passage was first published in 1940, just when Europe was falling under the rule of another group of self-proclaimed “superior Romans,” based in Berlin. They too boasted of their “primitive energy and ruthless will to exist,” and were equally determined to extirpate any “markedly inferior” races who stood in the path of their historical progress. Albright, though, saw nothing troubling in that analogy, and his text reappeared unchanged in a new edition published in 1957, a decade after the Nuremberg Trials. His comments would make sense as a form of veiled pro-Nazi sentiment, were it not for the source. But if Albright was not defending Nazi policies, as he assuredly was not, it is astonishing that he proved unable to think through the implications.

I am doubly intrigued by Albright’s account of Canaanite religion, with its sexual and sacrificial motifs. As I read passages like this, I actually have a powerful sense of déjà vu, and from an odd context. It sounds exactly like the kind of tabloid writing about “Evil Cults” that was common in the mass media of the 1920s and 1930s, and which was reflected in fantasy authors like H. P. Lovecraft, Henry Kuttner, and others associated with Weird Tales magazine. Another key idea of the time was that such alleged atrocities and Nameless Horrors were the direct continuation of authentic ancient pagan cults: this was the extravagantly popular idea derived from British eccentric, Margaret Murray. In later times, that becomes the standard fare of popular fantasies about Satanism.

Actually, I can point to a still closer analogy. Orgies, human sacrifice, ritual nudity, and serpent cults: for an average reader in 1940, this would have resonated instantly, as the core themes of the extensive tabloid literature of the era about Haitian Voodoo, with its overwhelming emphasis on racial primitivism. The most likely source for this picture would be the journalist William Seabrook, an enjoyable writer but a sensational fantasist of dubious credibility and bizarre sexual predilections. Much of the later mythology of Voodoo (and zombies) stems from his wildly best-selling The Magic Island (1929). Sadly, I don’t suspect that the sober Albright ever had a Weird Tales subscription (lovely thought), but he must have been reading the newspapers and magazines of the day, and (apparently) very credulously. Did he read Seabrook on Voodoo? Where else, in the 1930s, would he likely have found that package of human sacrifice together with “serpent symbols and sensuous nudity?” Do recall that Albright describes the Phoenicians as the “African Canaanites.”

I wonder whether Albright learned better in later life? In 1968, he published his Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: An Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths, which argued that Yahwism and Canaanite religion had actually gained from a mutual and even fruitful dialogue between the tenth and fifth centuries BC. As I read this later book, however, he does not seem to be retracting those older opinions of his.

Those genocide texts continue to disturb, and to appall. I’ll have more to say on these issues.

Brooke Sherrard has a useful piece on “American Biblical Archaeologists and Zionism: How Differing Worldviews on the Interaction of Cultures Affected Scholarly Constructions of the Ancient Past,” in Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84(1)(2016), 234-259.