Every morning, grasping for dear life that first crucial cup of coffee of the day (possibly in the mug that truthfully admits that I am “Tired as a Mother”), I open my work email. Sometimes there is a sense of dread – chances are, my inbox is filled with requests, reminders, and questions from students and colleagues, near and far. Responding to all these emails can take hours. Some get “triaged” for another day, if they are less urgent. A select few get Kon-Mari’ed as bringers of joy, and get to skip the queue.

While overwhelming at times, this never-stopping flow of email in the lives of those of us who have to corral a lot of emails as part of our jobs (meaning, not just teachers and academics!), is a practice with a direct connection to the rich tradition of pastoral epistolography, the writing of letters, in the early church. And so, my goal in this essay is to see if we can redeem email and consider its value as – dare I say it? – a spiritual practice that benefits us, blesses those to whom we write, and brings glory to God.

Let us explore this parallel tradition of letter-writing in the Roman world and the early church as a foundational framework that will equip us to construct a more beautiful and distinctly theological vision of work email. I argue that writing work emails to students and colleagues can become, when done lovingly and with gospel principles in mind, electronic epistolography for the glory of God. But first, how did we get here? How and why did email take over our lives so much anyway?

A Few Years Ago on a “Normal” Campus

The need to find a gospel centered view of email is one upon which I arrived fairly recently. It is connected to the changing nature of my work, whereby email has become a much greater part of my job than it had been originally. Judging anecdotally by laments over the burden of email from many colleagues at other institutions, my experience is typical. The increased volume of email in the lives of all academics these days, regardless of their institution, reflects the changing nature of our work, especially post pandemic. We used to complain about meetings that could have been emails. Now those meetings have indeed become emails, but most of us are not necessarily the happier for it.

Years ago, when I first began working as a professor at a regional comprehensive state university, I spent several days each week in my on-campus office. The campus was, quite simply, the place where I worked – taught, met with students for office hours and advising, attended on-campus events and countless committee meetings, graded, planned out lectures yet to come, read, wrote a little and, perhaps most exciting of all, had intellectual conversations with colleagues.

Many a conversation about teaching reluctant freshman historians, books we were reading, or projects we were working on ourselves, happened over a cup of terrible coffee and a chocolate-chocolate chip muffin the size of an average human cranium. RIP, downstairs coffee cart in my campus office building. Some of us still remember you fondly, and do not agree with the Risk Management Office’s assessment that you were a fire hazard and, therefore, had to go. No one really used that door that you were blocking, anyway.

Fast forward twelve years. Gradually, over the years leading up to the pandemic, student demand at institutions like mine has shifted from the traditional on-campus classes, meeting two or three days per week during the daytime hours, to increasingly more online classes and evening-time seminars that meet just once a week. Students have been voting with their feet, and virtually every class that my department has had to cancel over the past five years has been on-campus. Online classes, by contrast, have been filling with ease. For many students my institution gets – commuters, non-traditional age, and often first-generation college – the idea of attending college full-time and living on campus has simply been impractical.

But as the teaching on my campus has shifted more to the virtual realm, something has gotten lost in the process. Faculty have not needed to be on campus as much, so our sense of community began to drift. More significant, students in online classes do not come to office hours, which means that the challenges, big and small, with which they used to come and talk to faculty, simply go unresolved. We used to joke about students using office hours as therapy. The chilling reality more recently, though, is that students too often struggle alone without seeking help, unless we reach out to them first. When the pandemic struck, it was just the last hit of many for our quickly-disappearing sense of community.

A few months ago, historian Jay Green wrote about the post-pandemic loneliness of the faculty lounge at his own small Christian college, located less than three hours away from my campus. While his campus is residential and has always had a much better sense of community than mine, it was striking to learn that even his post-pandemic academic workplace has changed in significant ways. And academics are not alone in this shift. So many friends who commuted into an office before the pandemic have now transitioned to permanently working from home. My brother-in-law, a network administrator for a hospital, came home from work with a laptop in March 2020. He has not gone back into the office since.

Whether we like it or not, this is our new reality. Needless to say, not all of it is liberating or joyful. With this new work rhythm, there is a tangible sense of loss. My work-related communication has completely transformed from in-person conversations to written email dialogues over the past decade. Live interactions with people have largely disappeared while the email volume has increased exponentially. But there is a valuable opportunity here.

As an ancient historian, my research dwells on those periods in world history when people did not work in a typical office building, and very often could not have important conversations in person. Instead, they wrote volumes upon volumes of letters. Or, rather, scrolls upon scrolls and tablets upon tablets of them, to be delivered via the Roman imperial post, run by (literal) horse power. Too often we forget that the entire New Testament was written in a world where people could not easily have face-to-face meetings, and so they wrote letters. As crazy as it sounds, email communications can be the most obvious way for us to harness a practice that the early church obviously valued and considered spiritually significant — writing letters, even if not literally by hand on papyrus or wax tablets.

Electronic Epistolography for the Glory of God

The rich tradition of epistolography in the Greco-Roman world is a treasure trove of information for students and scholars of antiquity – the letters of Cicero and Pliny, for example, provide crucial insights on a variety of topics related to politics, everyday life, and provincial administration.

For the church, furthermore, letters have had a special significance from its earliest days – much of the New Testament, in fact, consists of letters (21 out of 27 books). These letters encourage, rebuke, and present sophisticated theological and philosophical ideas on a broad range of topics. Carried lovingly over hundreds or thousands of miles, they allowed conversations to continue for years among people who may never have gotten to meet each other face-to-face (or f2f, to use the modern academic lingo).

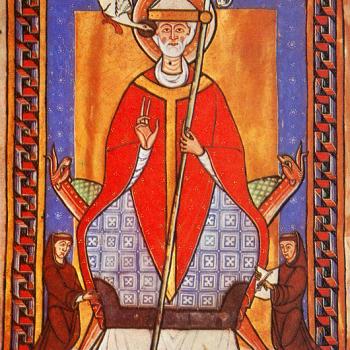

This tradition of letter-writing only blossomed further beyond the New Testament era, as early bishops and church leaders wrote letters to encourage and admonish other bishops, friends, loved ones, and members of churches, near and far. In her book Disciplining Christians: Correction and Community in Augustine’s Letters, Jennifer Ebbeler masterfully shows the significance of writing letters in the ministry of Augustine. Like Paul three centuries earlier, Augustine saw himself as part of an empire-wide community of saints, and he sought to edify, encourage, and sometimes rebuke members of that community through his letters.

There is wonderful application in this tradition of letter-writing for us, as we consider email theologically. These Christian letter writers’ experiences have something encouraging to give us now for our days of disrupted in-person communities, as we look for edifying alternatives. And so, I want to conclude with three common types of emails that we can and should be writing for the glory of God.

- Pastoral care for students and colleagues: So many letters both in the New Testament and in the writings of early Christian bishops involve pastoral care for saints in need – physical and spiritual. And this is certainly true for many of us in our work. Remember those office hours that used to function as therapy? Maybe the students in crisis no longer come to our office, but we can still reach out, ask why they missed an assignment, offer sympathy and support at a time of crisis, and offer encouragement for a task done well. Students in online classes especially seem to believe that they are invisible. Emails reassuring them that we know who they are, and care about them as real humans who exist outside just the virtual realm, are life-giving. And in corresponding with colleagues, such pastoral care is no less valuable, as everyone seems to labor under so much more stress than ever before.

- Emails of encouragement and gratitude: Academia is an environment that is profoundly critical and discouraging. There is a reason that bitter jokes about “Reviewer 2” are a regular part of the discourse. Whenever we read work by other academics, it seems that the primary aim, at least when reviewing that work, is to rip it apart, deconstruct, criticize and explain how much better we could have written it ourselves. And sure, sometimes criticism is necessary. But more often, we forego precious opportunities to build up and encourage. For years, I have read and cherished books, articles, and essays without even thinking of sending an author a quick email of appreciation. I am trying to break this habit now, although it still feels just a little bit strange to send someone I do not know in person an out-of-the-blue email commenting just how much I loved something they wrote! But there really are so many wonderful books and other publications out there, written by wonderful people. I am the richer for having read their work, and sharing my gratitude with the authors is ultimately a deeply spiritual practice, just as gratitude over the beauty of so many things even in this imperfect world should be.

- Advancing the evangelical mind over email: Email conversations with a few dear friends over this past year have showed me that yes, this is true, emails about theological and intellectual topics can advance the evangelical mind. True, we all miss the wonderful conversations we once used to have in person, and hope to have together again, whenever we happen to be at the same conference or event. But sometimes, the conversations we have over email dig deeper, and result in insights that emerge that benefit each other’s research. A comment from a friend might prompt a question, or one of us might share a reading recommendation. Finally, research accountability goes a long way in the long slog of working on larger projects. The evangelical mind thrives on intellectual community that is theologically robust. While anonymous peer review, that hallmark of academic publications, can be vicious and ultimately not helpful, comments on work-in-progress from kind and thoughtful scholars are a blessing to both the writer and the eventual readers. I was reminded of this recently, as a number of friends and colleagues took precious summer time to read draft chapters from my current book project and provide comments.

Last but not least, there is the farewell of every email. There as well the letter-writers of the early church have useful reminders for us. Just think of the theologically rich blessings with which Paul both opens and concludes so many letters. But if you are not comfortable writing out heartfelt blessings at the end of your emails, you could always borrow a sign-off from a letter writer who was not a Christian, but certainly believed in the significance of epistolary communication. In signing off on his letters, the foremost orator of the Roman Republic, Cicero, wished to his friends: “cura ut valeas” – take care!

Take care, dear friends, and stay well.