Last night, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), stepped out onto the balcony of the Presidential Palace in Mexico City to face a throng of people gathered in the zócalo – the first such gathering since 2019. At 11pm, the popular norteño band, Los Tigres del Norte, paused their outdoor concert and the voices in the square hushed as the president, holding aloft a Mexican flag, shouted various phrases, including: “¡Viva la independencia! ¡Vivan los héroes anónimos! ¡Muera el racism! ¡Vivan los pueblos indígenas! ¡Viva México!” (Long live independence! Long live the anonymous heros! Death to racism! Long live native peoples! Long live Mexico!”). The crowd responded with repeated shouts of “¡Viva!;” notable were the three cries of “muera” (death), apparently the first time a Mexican president has used this phrase in “el grito.” After ringing the palace bell, López Obrador turned to salute the soldiers who had brought him the flag as the national anthem played. Fireworks lit up the sky in red, white, and green, and the crowd danced and shouted. Los Tigres del Norte continued playing until a quarter past midnight.

This annual Independence Day ceremony on the evening of September 15 is one of the most important moments in a month-long, country-wide celebration of Mexico’s independence, a brutal 11-year war. The president’s words commemorate parish priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla’s shout (el grito) as he rang the church bell in the town of Dolores on September 16, 1810. Though no records exist of Hidalgo’s exact words, the essence of his battle cry was: “Long live Our Lady of Guadalupe, death to bad government, death to the gachupines [the Spaniards]!” Mexicans consider Hidalgo’s shout one of the most important speeches in their country’s history.

On this, Mexico’s Independence Day, I’d like to explore a religious, rather than political, piece of the independence movement, namely, the appropriation of the Virgin Mary during the war. But first, a quick look at Hidalgo’s brushes with the Inquisition for some context.

Within a month of “el grito de Dolores,” the Inquisition issued an edict of denunciation against Hidalgo for “Heretical Depravity and Apostacy” (Archivo General de las Indias, Ramo de Edictos de Inquisición, vol. 2, folio 69r-v). Though initially eluding capture, Hidalgo was eventually executed on July 30, 1811. A mestizo priest, José María Morelos y Pavón, took up the cause. Catholic priests as independence leaders – such a different story from our own.

The Inquisition’s October 13, 1810 edict of denunciation against Hidalgo was the culmination of a trial begun a decade earlier. During Easter of 1800, Hidalgo, alongside other guests, visited the home of a former student and fellow priest and his two sisters. Hidalgo supposedly joked about unorthodox theological positions and someone in the party reported him to the Inquisition, accusing him of supporting the French Revolution and holding beliefs contrary to Catholic teaching (Peter Force Collection, Box 8c, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress).

Witnesses testify about Hidalgo’s fitness to continue as a parish priest in San Felipe, 1800 (Peter Force Collection, Box 8c, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress)

Witnesses testify about Hidalgo’s fitness to continue as a parish priest in San Felipe, 1800 (Peter Force Collection, Box 8c, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress)

The 1810 edict of denunciation (English translation available in The Inquisition in New Spain, 1536-1820: A Documentary History, ed. and trans. by John F. Chuchiak IV) repeats several accusations listed in the 1800 testimony, bringing twelve charges against Hidalgo and avowing that he had continued for a decade in his obstinacy and apostacy. The document states that Hidalgo’s corruption prompted him to “place yourself at the head of a multitude of unhappy people, whom you have seduced…. declaring war against God, his Holy Religion, and our Homeland… now you preach… great errors against the faith, raising all of the villages to erupt in sedition with the cry of Holy Religion, with the name and devotion of the Holy Virgin Mary of Guadalupe, and in the name of our beloved King Ferdinand VII, which I allege is proof of your apostacy from our Catholic Faith and your pertinacious errors.”

Published bill of twelve charges against Hidalgo brought by the Inquisition on October 13, 1810 in Mexico City (Peter Force Collection, Box 8c, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress)

Published bill of twelve charges against Hidalgo brought by the Inquisition on October 13, 1810 in Mexico City (Peter Force Collection, Box 8c, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress)

There’s so much rich material in that selection, but I want to focus on the reference to Our Lady of Guadalupe. According to Catholic tradition, the Virgin Mary appeared as a Nahua (Aztec) noblewoman to a recently-Christianized Nahua commoner, Juan Diego, on a hillside outside Mexico City on the morning of December 9, 1531, ten years after the Castilians and their indigenous allies vanquished the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan. After Juan Diego made several attempts to convince the local Franciscan bishop that the Lady desired that a chapel be constructed on that hillside, she imprinted her image on Juan Diego’s tilmatli, or maguey-fiber working class cloak, and the bishop believed. The tilma (as it’s known) now hangs in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. Drawing in about 20 million visitors a year, it’s the most visited Catholic church in the world.

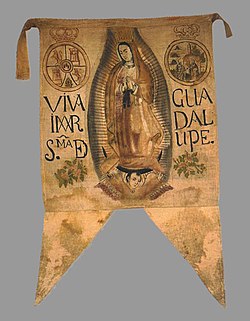

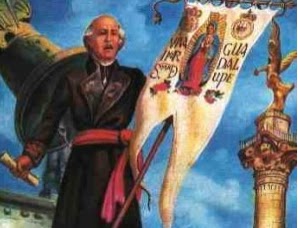

Guadalupe has come to symbolize Mexico. She’s a homegrown Virgin, as it were, not imported from Spain. This is why Hidalgo mentioned her in his cry for independence, and why he imprinted her image on his standard to lead the insurgents into battle: Long live our homeland under our heavenly patroness! The Inquisition and other Church leaders, including bishop-elect Manuel Abad y Queipo, denounced Hidalgo’s use of Guadalupe’s image as a sacrilege, citing it as evidence of his apostacy.

Miguel Hidalgo’s 1810 standard featuring Our Lady of Guadalupe (courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

Hidalgo carrying his banner (wikisabios.blogspot.com/2012/07/historia-de-la-bandera-de-mexico.html)

And yet the Castilians used images of the Virgin Mary as well. Of the many stories to come out of the Mexican Independence War, my favorite because it is so Mexican, is how the insurgents dressed up statues of Our Lady of Guadalupe in combat fatigues and carried her with them into battle. The opposing side responded by dressing up Our Lady of the Remedies in combat fatigues and carrying her into battle with them. The Virgin faced off… against herself. Why was this so significant?

Religion has always been important to Mexico, long before Europeans brought Christianity. As Jonathan Truitt has argued in his book, Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenochtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1523-1700 (University of Oklahoma Press/Academy of American Franciscan History, 2018), colonization did not change Nahua experience with the divine, it just changed the divinity with which they interacted. Catholicism permeates Mexico’s history and much of its present.

The use of statues and dressing up images has roots in both the Americas and Spain. Most of us have seen the elaborate Semana Santa (Holy Week) pasos carried around Sevilla with clothed statues and tears made of real diamonds. Some Spanish Catholic parishes have articulated statues, of Christ Crucified, for example, that can be taken down and laid in a tomb on Good Friday. Articulated statues and dressing images in clothing are Mediterranean Catholic traditions, and can be found in other countries in the region.

In some indigenous communities in the Americas, native priests would cradle divine images in procession. I published a piece in Fides et Historia 51:1 (Winter/Spring 2019) about a contemporary religious procession in Cholula, in the Mexican state of Puebla, that harkens to pre-contact processional practices. Because this procession takes place during the rainy season, participants often drape their images in rain slickers.

What I find interesting is that during the Mexican Independence War, these two traditions clash in the form of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Mexican Virgin, facing off against Our Lady of the Remedies, the Castilian Virgin.

In modern-day Mexico, each president adds his own style to “el grito” on September 15. Gone are the references to faith and the mentions of Guadalupe that Miguel Hidalgo and the insurgents found so essential to their declaration and their actions. Yet even if she is absent from presidential Independence Day commemorations, Guadalupe remains the symbol of Mexican national identity. As Octavio Paz famously once said, “When Mexicans no longer believe in anything, they will still hold fast to their belief in two things: the National Lottery and the Virgin of Guadalupe. In this I think they will do well. For both have been known to work, even for those of us who believe in nothing.” Add to that a common Mexican expression – “Todos somos Guadalupanos” (We’re all devotees of Guadalupe).”

¡Que viva México! ¡Que viva la Virgen de Guadalupe!