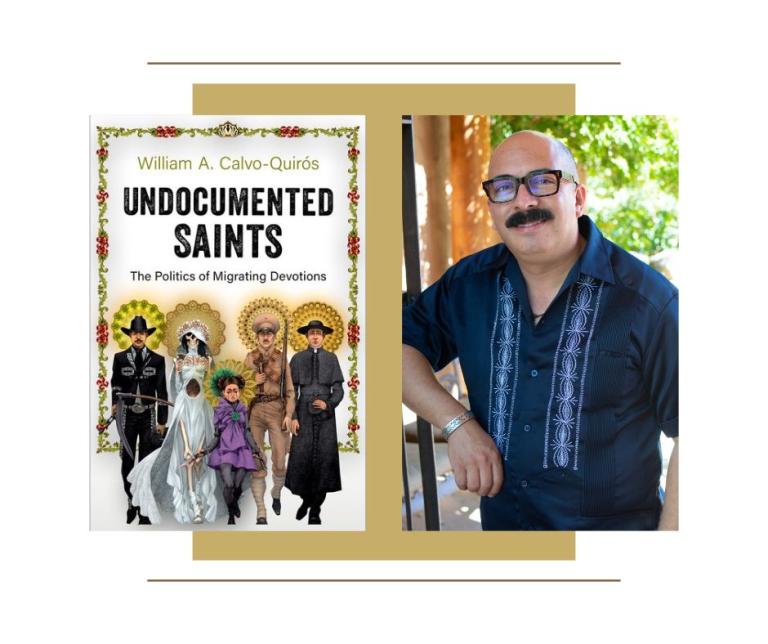

Interview highlights

On the “system of terror” targeting immigrants and the origins of this book

WCQ: “The best way to make God laugh is to give him or her a plan. And I came [to grad school] with a plan–you know, this is what I’m going to research and this is how it is. And life always turns things around, you know? I think the best thing you can do is open your heart for what the universe is telling you through the thing that you like. So it was very simple. Originally, I was doing research on Chicano methodologies because that was my biggest concern. How do we do research with the Latino community in a way that recognizes our uniqueness but also understands where are we located within academia? And I remember that I was visiting my family in Arizona. I was doing my PhD at that time at UCSB (University of California, Santa Barbara), and I was visiting my family in Phoenix. It was during the time of Joe Arpaio and Jan Brewer, and it was a very difficult time for us as Latinos. (If we only knew what would come later on in 2012!)

It was a very difficult time because it was really in many ways the implementation of the carceral state at the state level…The idea was to create this kind of system of terror that was constantly surveilling and trying to control people. It was a very difficult, difficult time with a lot of stress, and, you know, I’m an immigrant. My family’s immigrant and Latino, so we felt that it was very directed at us.

I remember that one of the things that was happening was many community events, many gatherings. One of these took place in Holy Family, a Catholic church in South Phoenix…The idea of the event was to have lawyers drafting documents for some of those immigrants in order for them to legalize in some way the custody of the children, so in the case that the parents were deported, the children can stay here because they were American citizens with a family member who had documentation. It was a very terrifying time because people were just signing papers to leave their custody to their older daughter, or to their aunt or to their uncle or to their neighbors because, as we saw later on, many children get lost in the system. It was really a system of terror. So it was a gathering that happened in a Catholic church because at that moment, following a little bit the sentiments of the sanctuary movement, the idea was that it [the church] was a place that was safe for people…I was there helping with my mom to help and support these people also because it was close to where my family is located. Afterwards, there was a little prayer event…[and] in the corner of the altar, there was a lot of flowers with an image of a saint. So I asked my mother, Hey, Mom, who is the saint? I don’t recognize it.

She said, Oh, that’s Toribio Romo. He’s the saint of people without documentation in the United States. He’s supposed to appear along the border and help people cross the border without documentation. So we call him a holy coyote, a holy smuggler, Santo. And I was thinking, Whoa, that’s that’s interesting–this kind of intersection between the extremely religious, the almost vernacular folklore of the story of a saint, and the drama that these people really experienced everyday because of the lack of documentation to work here in the United States. So that’s how I think the project began. First, as idea: who is this guy and why did people venerate this guy? How is the veneration happening?”

On interpreting saints as a “social text” and a “cultural archive”

“Now, I need to say that there is also another story…Years before I went to seminary because I thought that I want to be a priest, a Catholic priest. So I moved with an order in Florence, in Tuscany, Italy…I remember that during one of my classes on church history, one of the professors said something very interesting. He said that normally when religious communities teach these classes, it focuses on the different documents that the church had created, the councils–you know, the Council of Trent–that respond to the reform. So different councils have been crucial because it’s like a public statement. They are historical statements that respond to a particular crisis in the church, and the church, for the most part, is trying to adapt to these changes…

You can also tell the story of the church by the different saints that have appeared at different periods because they respond to the needs of a particular community. From the faith point of view, of course it’s the Holy Spirit, but if we think about it, it really is a social text that says something about the struggles of these communities at that particular time… So I think my book came from the intersection of those two realities: one, the vernacular saints among people of color and among Latino communities and immigrants, and then the notion that in many ways, we can use the experience of these different saints who have appeared within those communities to tell us something about the struggle that they’re going through.

The book’s main narrative is really all about how you untangle the political and religious and social components in each one of these saints. It’s [about] five different saints, and at the beginning, they follow kind of a chronological order. Now it’s a little bit difficult because with the saints, we have a social element. You may have a moment when the saint is born or is dead…but with some of those saints, there is no correlation between the moment when they die and the moment when they became popular. There is almost like multiple resurrections of multiple deaths: one is the actual moment [when they die], assuming that it’s a real individual, but the other is when the devotion becomes relevant or more popular or more widespread…

Anyhow, the book starts around 1845 and goes all the way to the present…If I think of the saint as a cultural archive, how do you study them? You can study, of course, the historical figure. Where did they die? How did they die? What was happening in the community in terms of the economy or the politics? That can give you a way to enter into the saint. My argument in many ways is that all of [the saints] truly respond to a particular crisis… Saints are very interesting because we attach to them particular powers or particular characteristics. They respond to something specific that we’re looking for. So if we think about Santa Maria Goretti as a saint to help issues of abuse and rape–it’s because she died under those circumstances. You need to understand the story of the saint and the context in order to understand that devotion.

At the same time, over time, many of those devotions change. So for me, it was important to understand the social, political, economical context, but to not get trapped only in this kind of deconstruction as if the people were getting into those devotions only in some kind of utilitarian way. Because there is faith. How do you quantify faith? So each one of those saints, I’ll follow them from the moment when they emerge or die and how, little by little, different meanings have been attached to that particular devotion.”

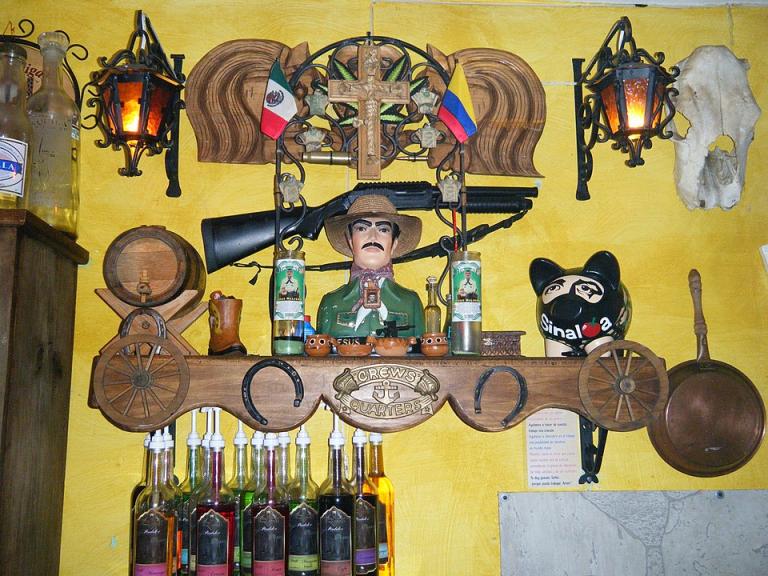

On Jesús Malverde, patron saint of drug traffickers

“For example, the first one is Jesús Malverde. It’s 1845, a moment of deep transformation in Mexico, what we call the encounter with modernity and industrialization. [Malverde] died in a little town of Culiacan, part of Sinaloa. We may hear about it because it’s the capital of narcos in Mexico…in this case, it had been for a long time associated with this kind of narco-saint. I studied the emergence of the saint, but more important, how people told the narratives about the past, about this saint, to understand a little bit of the changes that the city experienced because of the Porfiriato, the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, who led to the Mexican Revolution…I follow his story all the way to the present and how it suddenly merged with narco-capitalism. Now we talk about him in mass media, to the point that when the El Chapo Guzman had his trial in New York, an image of the saint appeared in the courtroom. Clearly somebody brought the figure there, and we understand that it was used as a means of intimidation to some of the witnesses because they see the image there, and they say, Well, it’s not just human power who will go after you if you testify against against the Chapo, but also spiritual forces will go after you.

Recently Telemundo decided to do a telenovela (you know, it’s a very important for Latinos) about the life of Malverde. And the main actor that they were planning to [use] was very well known. At one point, he disappeared from the project, and we find out there were all these rumors that the reason why he needed to leave behind this project–somebody who is one of the highest paid, most recognized, most good-looking Mexican actors–was because for a long time there had been this gossip that he’s gay. It looked like at one point the cartel got upset that he was the person representing the saint, and they thought that it cannot be a gay man. They threatened his life, and he decided to leave the project. So for me, it’s very interesting because that chapter is about a saint, but it’s not really just about the saint. It’s really about the construction of masculinity, especially after the Mexican Revolution, and the connection with different economic practices…

The saints are cultural objects that shift meanings over time, and there are many different forces–cultural, political–that are at play that allow these kind of devotions to evolve, emerge, change, and disappear. So I think in this case, it’s all about a story within a story: the story of a saint, within a story of a community who is migrating, how migration shifts that religious experience, but also how religion changes how we experience migration…And because I study saints who are cultural objects, we see how a devotion to a saint changes over time, but also changes in different places, even within the same individual. So that makes a person’s devotion to Jesús Malverde in their hometown very different to the one that we have here.”

On the Catholic Church and the problems with the “notion of a monolithic religion”

“Even when we think about Latinos…they’re not something that is fixed. It changes over time, and therefore, our religious practices change. When people say, Oh, well, they’re Catholics–well, that’s a loaded term because being Catholic means something different in different times and different places because of the experience of migration. So if you live in a Catholic community in the United States, it’s different from the one that you have in Mexico.

…I think what is very interesting is how monolithic we sometimes think these migrant communities [are]. We think that they are fixed, that they do not change, that the personal decision to move is the same. And my experience is that we are always shifting, that our identity is always changing. I mean, they say we don’t end changing our identity when we die because there is always new narrative and new meanings that we add to our lives.

…Even within the Catholic experience–that is the community that I study–we find out that what it means to be Catholic [varies], and people have differing layers of alliances or connections within the Catholic Church…The Catholic Church is like a train with many different wagons, and people are sitting in different wagons, and sometimes they stay fixed, but sometimes they move to one wagon or the other, or sometimes even moving within the same wagon does not mean that you will get faster, you know. There are very different constituencies. For example, in my work, I found that people say, well, I’m Catholic, but what the church understands, as an institution, what it means to be Catholic is very different to what it means for people actually in the ground.

So the church says you cannot follow the devotion to La Santa Muerte. It totally goes against the dogma of the church. But for so many of these immigrants who venerate the Santa Muerte, there is not even conflict…They just go in the morning on Saturday or in the afternoon and start a service with a Santa Muerte, and the next day they will join the rest of the other community to go into a Catholic church. So people think that religion may be fixed, but even within the community, it changed. Now, people may have differing alliances. They may be Catholic, what I call cultural. They say, I don’t believe in many of the things that the church [teaches]…But when my grandmother [dies]or when I need to get married or when there is a moment of difficulty, I pray or I go to church. So I think one of the things that the book does is to help people understand that there are many different layers or tendencies of participation within the Catholic Church beyond even the interpretation that the Catholic Church officially has about its own members. I mean, they may call the person Catholic just because the person got baptized, but they don’t see that some of those people say, Well, I’m not Catholic anymore, despite the fact that I go to Mass here and there. What I’m trying to say is that this notion of a monolithic religion, it is not real, and many of those categories that we have used for a long time to understand people do not work, especially when we deal with vernacular devotions. Some of them are adapted and recognized by the church, but some of them not–even, for example, the definition of a saint. There is the definition of a saint defined by canon law, and there is a definition of sainthood by the people in the streets. They may be very different to the one in the church. It is almost irrelevant for many of these people that the person had been recognized by the church because it’s about how effective they are in making miracles and helping people to survive everyday. A saint is a saint if people can tie it with a particular miracle, a particular need.”

On Juan Soldado and “religion as an archive for the drama of everyday life”

“Another [way] that I think the book may be useful for those who do research in the Latino community is to unveil religious sites as the archives that record the drama of everyday lives. The chapels are not just a place where you go and pray–it’s mostly a place where pain is inscribed in the different devotions and different petitions. The people ask the same. So when I go and study Jesús Malverde or Toribio Romo and you go into this chapel that has been decades in the making–layers and layers and layers of different letters or requests–it’s also a miracle that tells us about a very complicated story of migration.

I’ll give you an example. When you go to Jesús Malverde, there are many different players. There are the people who put up the little photos, but there are also the people who are managing the chapel who decide which photo will be there and which [will not] and which one will go to a different place because there is even hierarchy among those things. That’s one thing. Many scholars, when they were early in the research on Jesús Malverde, they would say, Oh, it’s a clearly explanation of the narcos’ interference in America. And it has nothing to do necessarily with that. It had to do with that trajectory that people follow as they look for jobs.

So with Juan Soldado: very simple. Scholars did research one time, and they found people say, Juan Soldado, help me to cross into the border. Now the version that I found fifteen years after is just not enough. Help me to cross the border, they say. Help me to cross the border. Make me be invisible to la migra. Help me to get a job and keep the job. Help that my family does not come after me, you know, so let the people understand the complexity of moving into the United States. So I think something that I love about my research is that it’s about a migrant who is not naive. That is, they understand the many forces that are in place that have forced them to move out. Now, they may not use terms like International Monetary Fund or the policies of neoliberalism. They don’t use those terms. But they use the devil is after me and the devil means I lose my job, my family disintegrated, there is violence. So if I want anything for people reading the book, it is to understand religion as an archive for the drama of everyday life for these migrants, a drama that goes in one direction and that may go in the other direction as well.”

On the role of saints and Catholic devotions in the transnational lives of migrants

“When I began my research, I thought, Oh, it’s about devotions that emerged in Mexico and all the drama that happened around them, and then they migrate into the United States, and then it’s about all the drama about these people here. And in many ways it’s true; that thing is still happening. When you think about Toribio Romo, who is the saint for people without documentation, the drama that these people experienced in Chicago, in Detroit, in Tulsa because of racism that is so linked to that devotion is really unveiled. [And there is also] the drama of the Catholic Church that does not know what to do with these people, the drama of feeling that they’re not welcome and trying to survive, the drama to fulfill a promise to a saint that you cannot do because you don’t have documentation in the United States…

So what do you do? You build a chapel that looks exactly like the chapel that you have in Mexico. It’s totally transporting yourself. You say, I don’t need to leave the United States. I go to this chapel, and through some kind of magical spiritual forces, I am transported [to fulfill] my devotion, my promise back in Mexico. It means that you build a chapel that looks exactly the same, that is by the same architect…then you bring a priest for that place to bless it, etc., etc. It is almost like Star Trek–poof!–it’s taking you to the other place. Why? Because the drama of migration laws that help keep these people trapped in this kind of golden cage, as we can call it sometimes.

But as the as the research was moving forward, I started to feel even how limited that position was because I found that I was taking credit away from these migrants because they were also transforming Mexico and religious practices there. How? Some of them were sending money by hometown associations, and we had so many of them. They will say, Oh, we want to build, we want to help repair the roof of the church or I’m going to pay for the patron’s space in my town or I’m going to sponsor a particular devotional practice in my town. So they are impacting directly that church in Mexico because they’re finally funding with money to the point that the devotion of Toribio Romo is a devotion of return…

The priests in these parishes will travel and do a pilgrimage to the United States to meet the devotional groups here because it’s a way to seek funding for their own communities. I mean, a little town that has 300 people becomes a town that has 30,000 people that visit during the weekend: imagine that transformation and what it means for this town! I mean, they build hotels, restaurants, a new bigger church because all the drama of migration…

But what is happening is that migration is not coming only in this direction, but also these people are going that direction because of all the remittances and also because many people have been deported. And these people, many of them encountered the devotion not in Mexico, but in the United States. So they go back now to a setting that has been putting the devotion in place. Now what happens? If I’m in Chicago, and somebody gets deported from Chicago, and I have a hometown association [in Mexico] that is getting money to send to the church I want to send the money to, I want [to find] somebody there that I know or somebody that I trust. So that individual who has been deported, who maybe grew up in the United States, who speaks English, who understands American systems, becomes the anchor for the hometown association and the representative of that town. So suddenly there is social capital that comes to play in the drama and the paying of the deportation…it becomes a way to connect to the United States.

So when we think about the United States of America, we start seeing the interference of America in religious practices outside because that individual is not the same Mexican child or young guy who was here. He left, he lived in Chicago, he learned the language, he understood the system is not the same. The person has experienced American culture, and they move with that…

But the thing that is interesting is that now the saints and the devotion to the saints becomes the channel for giving funding back and forth. So the saying is that the biggest miracle of many of the saints is it’s not just happening here in the United States, but it’s happening in Mexico, as this kind of process of migration is affecting both sides. I’ll give you an example. The Catholic Church in Mexico in the 1930s, they were totally anti-immigration. They did not want people to come to the United States because they thought they’re going to lose their faith…They were Catholic, [but in the United States] now they were going to be exposed to liberal Protestantism, and [the Catholic church] will lose them…Toribio Romo, the saint that helps people to cross the border without documentation, wrote a piece where he actually said that those who moved to the United States…were not man enough, they were not Mexican enough. [It was a] total homophobic text against migration, and he is the one who turned into that saint of migration decades later. Why? Because it’s the church itself that understood that this is a wave that you cannot stop.

So what is the task now? It’s not necessarily to prevent the people to leave. But how do you walk with them on the via crucis of their migration? You know, I remember when we were together once, we talked about this kind of a little pamphlet, a prayer book, the passport of the migrant…a set of prayers written by the Catholic Church, by the Diocese of Los Lagos, to help the person understand and navigate the process of migration. There is a prayer for the moment that you need to tell your family that you’re leaving, there is a prayer for the moment that you arrive at the border, there is a prayer for the moment that you need to look for a job, there is a prayer for the moment that immigration finds you and the moment that you…have been deported, and another prayer for the moment when you need to encounter your family after being deported…The language of religion gives meaning to the different steps of this process, but it’s also to help the individual to understand what they do.”