Last month, I enjoyed attending the Baylor Institute for the Study of Religion’s virtual conference, “Evangelicals on Their Past: Studies in the History of Evangelical Historiography,” organized by David Bebbington. The overarching research question Bebbington returned to regarded the legitimacy of confessional histories and their distinction from professional histories. As I mulled over the presentations, I, too, wondered about my perception of the making of the evangelical past. As the conference concluded, the ethical dimensions and implications of evangelical history occupied my mind. I drew two lessons from what I learned. Evangelical historians must meet the ethical demands of treating the dead with dignity and honoring their fathers and mothers.

Treating the Dead with Dignity and Honoring Fathers and Mothers

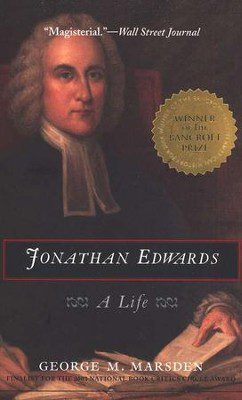

During the conference, one historian, Ian Clary, invoked George Marsden as an exemplar of professional evangelical history writing. Clary did so in an effort to honor one of his father’s of evangelical history. Clary recounted an oral history on the sticky situation Marsden found himself, when Iain Murray, a confessional historian, critiqued Marsden’s biography of Jonathan Edwards, published at the tricentenary of Edwards’s birth (Jonathan Edwards: A Life [Yale, 2003]). Murray, as an ideological heir to Edwards and defender of his heritage, did not care for how Marsden treated the dead, Jonathan Edwards.

Murray’s confrontation with Marsden must have troubled Marsden, who undoubtedly never wished for his work to be considered an affront to Edwards, his legacy, nor his heirs. Marsden’s self-perception of himself as a professional historian undoubtedly was that he had dignified the dead, Jonathan Edwards, with care and honor. I couldn’t help but notice Clary’s apparent conflicted dilemma as he recounted this dispute between two historians of Edwards. Here were two fathers of evangelical history, who Clary wished to give due honor. Yet, one contested with the other over how the dead ought to be treated.

This anecdote conveys two assertions on the ethics of constructing history. First, evangelical historians have a responsibility to honor their fathers and mothers in the historical tradition. Second, evangelical historians have a responsibility to dignify the dead. The first observation is indebted to the Reformed tradition of faith, especially the section of Thomas Watson’s Body of Divinity on The Ten Commandments. The second observation is indebted to Beth Barton Schweiger’s essay, “Knowledge and Love in History,” from Confessing History: Explorations in Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (60–80).

Dignifying Dead Evangelicals When Constructing History

One of the fundamental questions evangelical historians must ask, when constructing evangelical history, is what would the dead, the subjects of our study, think or say about their evangelical role qua evangelicals? Are we honoring the dead? This might generate a whole series of questions that must be considered. Did the dead call themselves evangelicals during their lives? Could there be evangelicals before a self-conscious understanding of evangelicalism? Have we properly constructed the temporal, spatial, and ideological boundaries of evangelical history? Have evangelical historians included periods, people, and places that are beyond the bounds of evangelical history? Why might evangelical historians have constructed bounds too liberal or too constricted?

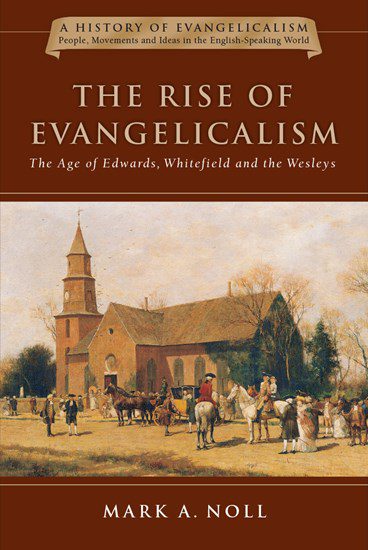

I have been wrestling with these questions because I am developing a spring course at Wheaton College on “The Rise of Evangelicalism,” which will use Noll’s first volume in the IVP series on evangelical history as a textbook. During the course, I will ask myself and my students these research questions as we explore Western European civilization from the sixteenth century through the Ante-Bellum era of the United States, with an eye especially to when, where, and who might be found at the headwaters of evangelical history. I intend to both honor Mark Noll as a predecessor in constructing evangelical history while also dignifying dead evangelicals, too.

Treating the Dead with Dignity in the African-American Christian Tradition

The anecdote concerning Murray versus Marsden and the confessional versus professional treatment of the dead struck me as being of great consequence as I’ve thought about developing my course on the rise of evangelicalism. You see, the past concerns and tensions between how a confessional and professional historian treated the dead can be carried over to present day corollary concerns and tensions about how the dead have been and ought to be treated in studies of race history. We should dignify the dead. To do so, we have to tread cautiously as we work with the past.

For instance, if I, as a white male evangelical historian, attempt to retrieve the past of African-American Christianity and portray its biblicism, it would be a valuable contribution to African-American Christian historical studies. But it would be overreaching for me to propose that African-American Christians, across the history of the United States, ought to be included within the story of the evangelical past because they meet the criterion of biblicism, an acceptable ideological marker of evangelicals.

Why should I tread cautiously here?

I should consider how present-day African-Americans perceive this revision of their past? Do black Christians or historians of black Christianity perceive their forerunners as black evangelicals? Has there ever been, is, or might there ever be such a construct as black evangelicalism? Might some take it as an affront to how their dead have been treated if white historians like myself reconstructed their history as a history of black evangelicalism? Might they perceive this history as being an ideological perpetuation of anglo imperial and colonial impulses? Might they feel that their dead have been forcibly displaced and enslaved into a paradigm not of their choosing?

As a white male historian, it would be presumptuous for me to speak on behalf of the heirs of African-American Christianities. I have to leave that task to other historians more fit to the task.

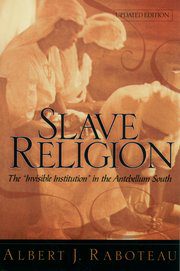

While Albert Raboteau’s research, from Slave Religion, masterfully conveyed how African-American’s employed the bible as they constructed their identity, Raboteau also analyzed the significance of death ways in the African tradition. In Slave Religion, Raboteau conveyed how Africans dignified the dead, honoring and remembering them with care, knowing that if they did not do so, the spirits of the dead might return to haunt them. This tradition was exported from Africa to the Caribbean and to the continental United States. Undoubtedly, African-American Christians today have a tacit remainder of that pre-Christian heritage to honor the dead, and they would be extremely concerned with how a white male evangelical historian like myself may inadvertently mistreat their dead. Needless to say, evangelical historians must prioritize the concern and consider the paragon weight of how the dead, their historical subjects, ought to be treated. Otherwise, they subject their work and legacy to tenuous footing.

Re-Visitation of the Dead, Jonathan Edwards, as Evangelical

One fascinating aspect for evangelical historians practicing evangelical history to consider is that the ethical demands of how they treat the dead has practical consequences, for evangelical historians believe the dead don’t stay dead. Our metaphysics indicate that evangelical historians will come face to face with their subjects one day, and they must give an account for how they have treated those subjects, how they have treated the dead.

Returning once again to the matter of Jonathan Edwards, the evangelical past, and how the dead ought to be treated—one day I might visit with the triumphal Jonathan Edwards in heaven. I should consider, does Edwards perceive himself as one of the founding heirs to the evangelical tradition? If I visit with him, might he gently push back, in rigorous and hearty dialogue, with points of clarification, for how he might differ from evangelical historians’ interpretations of him as an evangelical?

Evangelical historians have a pattern for casting the net, both confessionally and globally wide and liberal, as they set the bounds of the evangelical criterion of biblicism, in order to include the largest catch of fish possible into the evangelical family, and they long have included the prized catch, Jonathan Edwards, within the pool of evangelical biblicists. However, Edwards’s typological interpretation of Scripture does not meet the conventional evangelical biblicist criterion, as it has been understood and conveyed by writers of evangelical history. Surely, Edwards was a pre-critical biblicist. The finest among evangelical historians have argued so. But, simply put, Edwards was not a biblicist according to a modern, scientific, and deductive standard of plenary interpretation of the bible. In fact, if Charles Hodge is considered the measure of the standard for a first-order biblicist, then Edwards falls far short of the standard. Hodge, himself, trenchantly opposed the consequences of Edwards’s biblical and theological study. No doubt, other evangelical biblicists would find Edwards’s exegetical techniques and interpretations of scripture to be rather peculiar upon close examination.

Furthermore, perhaps Edwards’s atonement theory does not emphasize penal-substitution enough to meet the criterion expected of an evangelical by evangelical historians. Yes, he believed in a penal-substitution view of atonement, but he repeatedly argued throughout his works, in regards to his view of the atonement, that “to obey is better than sacrifice” (1 Sam. 15:22). In other words, he foregrounded the satisfaction view of the atonement—where the righteous obedience of Christ, from incarnation to exaltation—takes precedence over penal-substitution.

Thus, it would require some manipulation for a savvy historian to situate Jonathan Edwards as an evangelical, according to conventional, modern evangelical criteria. At least on two points of Bebbington’s quadrilateral would a historian have to perform reparative work to dexterously place Edwards within the bounds of ideological evangelicalism.

Dignifying the Dead and Honoring Elders: Universal Traditions in the Atlantic World

One of the profound gifts of historical work is that it is a science that continues the time-honored tradition of dignifying the dead. One of the disappointments of modernization has been the evolution of how the dead have been treated.

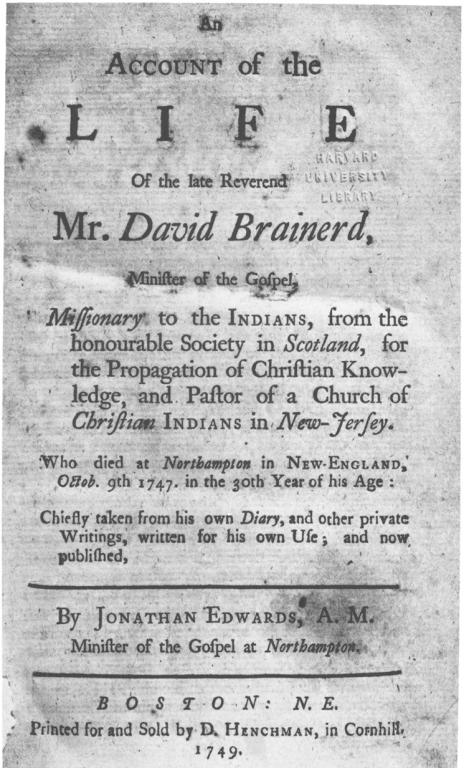

For generations, early modern Western Europeans treated the dying and the dead with care. They lived in a world under enchantment. As a person’s death neared, the community believed a contest took place between the forces of good and evil. The angels of Michael and demons of Lucifer contested over each soul. People engaged in a deathwatch to see how a soul maintained fidelity to Christ and resisted the devil, even to the end. After a person passed, heirs protected their legacy with remembrances. One may turn to Edwards’s publication of the The Life of David Brainerd to see how vital death ways featured in eighteenth century memoir. A full third of Brainerd’s biography recounted his decline and death.

The tradition of Western European death ways has universal parallels, which transcend the watery deeps that divide continents, peoples, and religious expressions. The Atlantic World has always concerned itself with how the dead ought to be treated. Universally, humans care about how the dead are treated and remembered.

My appeal is that evangelical historians should take stock and interrogate themselves, asking the question, how have we cared for the dead? Are they remembered as they ought to be remembered? Have some evangelical historians unwittingly made the dead instruments of their own ends? Have the dead simply furthered the aims of ideological commitments and conquests? Have some evangelical historians retained a tacit imperial and colonial mindset, inherited from Western European tradition and heritage, as they attempt to reconstruct a global and catholic evangelical Christendom?

Likewise, another aspect connected to honoring the dead, is honoring the living while they are still with us, especially giving due respect to elders in the community. This also is a universal principle perceived throughout the history and space of the Atlantic World. Whether in Africa, Latin America, Western Europe, or North America—humans have observed the time honored tradition of dignifying their elders. It’s only prudent for the young to do so. Junior historians, such as myself, have to constantly interrogate our own lives and ask ourselves, am I honoring my mother and fathers, who are evangelical historians.

These ethical appeals, to treat the dead as they would wish to be treated, to respect the wishes of their heirs, and to honor our fathers and mothers, does not set the bar too high, for those who are committed evangelicals and professional historians. It only expects us to live up to the excellent and exemplary standards, for which has set us apart, as evangelicals and professionals.

The Life of David Brainerd as Pattern

Once again, we might look to the dead, Jonathan Edwards, one last time for instruction. We might revisit his editorial work, The Life of David Brainerd, and ask: Is it a consequential example of how evangelicals have honored the dead well? Or, what if, this is one of our blind sides, where we repeatedly fall short of dignifying the dead properly?

Here we have a spiritual father attempting to honor a spiritual son with a panegyric. Historians have noted how Edwards bowdlerized Brainerd’s life when they compare Brainerd’s original journals to the edited publication. Edwards formed Brainerd into a more moderate, less enthusiastic, and less mystical evangelical than he was. Edwards intended Brainerd to be an exemplar for true religious affections and the devout Christian life. Edwards exalted Brainerd to vindicate his other revivalist writings, and he domesticated Brainerd’s New Light excesses to do so. This text set a tone for other New Lights to tame themselves, to reform their manners of revival. Samuel Buell and James Davenport, once radical New Lights, matured into moderate, respectable revivalists in the later third of the eighteenth century. They did so because moderate New Lights won a battle on the polite and socially acceptable mores for conducting revival. Edwards’s publication of The Life of David Brainerd shaped this image of a moderate New Light by setting Brainerd up as an exemplar of one.

Perhaps we might have to face the stark reality that The Life of David Brainerd signals a blind side of evangelicals, where we have an impulse to mishandle the dead. While well-intended aims motivated Edwards’s creative revisionist history, resulting in inspiring a global missions movement. In some way, Edwards set a pattern that gave evangelical historians permission to mistreat the dead and ignore the ethical demand to dignify them properly.

What a Person Thinks and Does with Jonathan Edwards

The trope that Jonathan Edwards fulfills in this essay is not lost on me. He is one of the first figures in history that those who love evangelicalism and identify as evangelicals wish to claim as evangelical. He is also one of the first figures that those who loathe evangelicalism wish to smash as they participate in the ideological iconoclasm of evangelicalism. While some say what a person thinks about Billy Graham is a good rule for defining whether that person has an affinity for evangelicalism, I am equally convinced that what a person thinks and does with Jonathan Edwards is an equally powerful tool for determining whether that person has an affinity for evangelicalism.