Today we have the pleasure of having a guest contribution from Allison M. Brown. Allison M. Brown is a PhD student in historical studies in Baylor University’s Department of Religion. She received her MA from Wheaton College (Illinois) in history of Christianity, with an emphasis on the Reformation. She has published on the Bible and nationalism in Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception (De Gruyter) and has forthcoming chapters in The Oxford Handbook of the Bible and the Reformation and Brill’s Calvin and the Old Testament.

“What’s interesting is, I hear a lot of people—when speaking about girls and women empowerment—you’ll often hear people say, ‘Well, you’re helping women finding their voices and I fundamentally disagree with that. Women don’t need to find a voice, they have a voice, and they need to feel empowered to use it, and people need to be encouraged to listen.’”

Meghan Markle spoke these words in 2018, addressing the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements at the Royal Foundation Forum. However, the British royal family generally abides by the “”never complain, never explain” rule, and senior royals—like Markle—are not encouraged to comment, explain, or defend their actions to the public. But, Markle still made her voice heard—through words, yes, but also with fashion.

British royal fashion, including that of Markle, has been tracked and analyzed by Elizabeth Holmes, author and multimedia reporter, on her wildly popular Instagram series #SMT (#SoManyThoughts). Holmes continually reminds her readers royal fashion is not a frivolous and unimportant pursuit, but a vital means of communication and public relations for royal women. From Markle’s 2018 minimalist Givenchy wedding gown to her emerald Emilia Wickstead cape dress for one of her last official royal engagements, Markle was saying something with clothing, making bold statements about her own understanding of her role as a senior royal in the modern era.

Markle’s statement about women having a voice, even if we don’t hear them, and Holmes’s focus on royal fashion as a “text” to analyze and consider important have both shaped the way I understand history, especially the history of Christianity. While desperately wanting to include voices of women in the church in syllabi and in my own research, I’m sometimes frustrated at the lack of sources. Where are the theological tracts, the legal documents, the letters, the art, the commentaries? We can and should talk about why women generally don’t produce the sources we have traditionally studied to illuminate the past. But here I do not want to discuss whether women have a voice or why they seem not to, but rather how we can listen to women’s voices.

By listening, we can better understand the ways women exerted authority and influence in the Christian tradition throughout the millennia, and also how, by expanding formerly restrictive categories to include women’s actions can enrichen our understanding the Christian tradition itself. I want to introduce a few scholars who have listened to women’s voices and expanded my perspective on what can be a source.

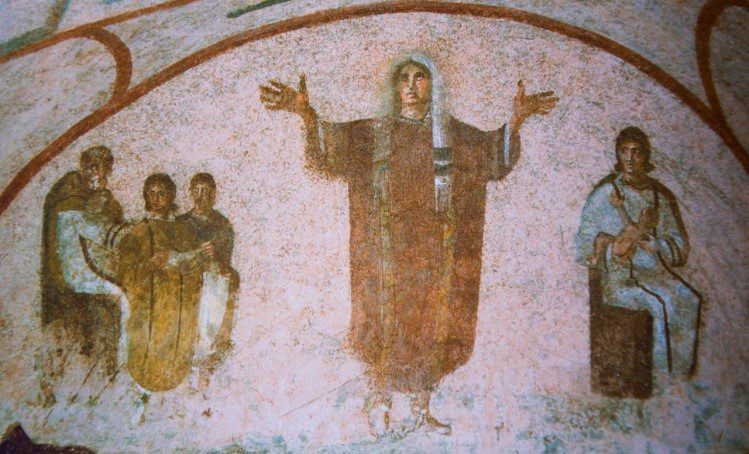

Karen Jo Torjesen’s article, “The Early Christian Orans: An Artistic Representation of Women’s Liturgical Prayer and Prophecy” appears in Women Preachers and Prophets through Two Millennia of Christianity (University of California Press, 1998), edited by Beverly Mayne Kienzle and Pamela J. Walker. Torjesen highlights several portrayals of orans, women in the early church in active and prayerful poses. These women—and they were almost always women—are likely representing the office of prophecy and prayer in the early church. While this was not a preaching role, the role of prophecy and prayer was vital in the worship of the early church and this role was occupied by women. If we focus merely on preaching or ordination as a category of religious power, we miss out on comparable (if not equal or greater) positions of authority women occupied.

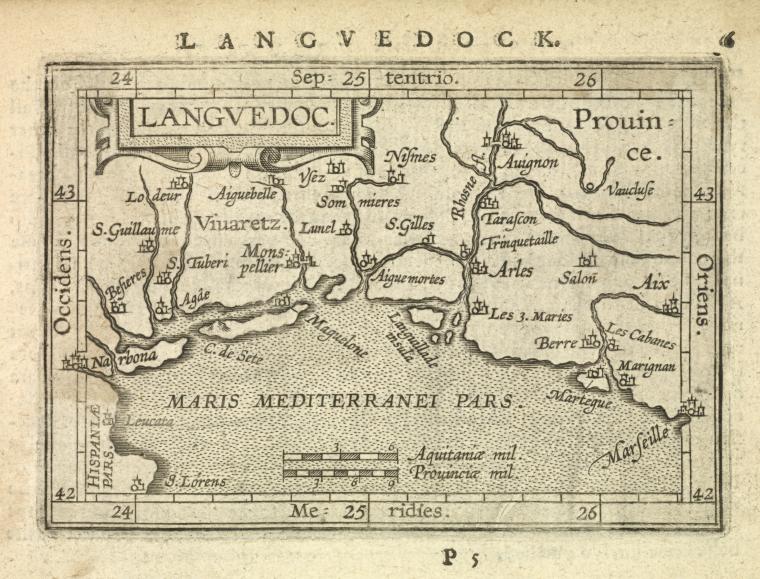

In The Voices of Nîmes: Women, Sex, and Marriage in Reformation Languedoc (Oxford, 2019), Suzannah Lipscomb uses the consistory records of Languedoc to provide a glimpse into the everyday experiences of sixteenth-century French women. These moral and spiritual disciplinary records allow us to see a glimpse of how women spoke, acted, and understood marriage, faith, love, friendship, and sex, and their feelings, attitudes, strategies, and motivations. The records also reveal how the consistories, in their regulation of women, also empowered them, among other things, to denounce those that abused them. Women’s voices are “mediated, curtailed” in these records. But, Lipscomb concludes, they are “audible” (4). We just need to listen.

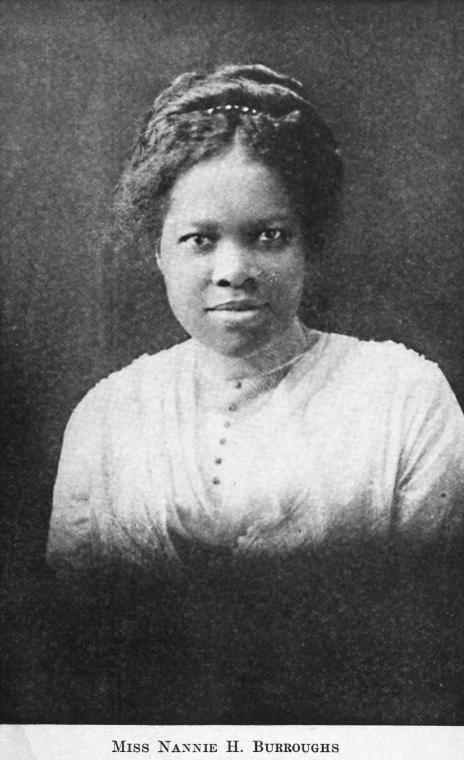

This Far By Faith: Readings in African-American Women’s Religious Biography, ed. Judith Weisenfeld, (Routledge, 1996) also showcases how women’s voices can be heard. Marie Jeanne Adams highlights Harriet Powers created pictorial quilts featuring scenes from the Bible. Powers was born an enslaved woman in 1837 and could not read. Her vibrant depictions of biblical stories of judgement, deliverance, and hope reveal how Powers understood the Bible through the lens of her own experience (26). Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham also illuminates previously unheard, but audible voices in her article “Religion, Politics and Gender: The Leadership of Nannie Helen Burroughs.” Although women traditionally have been the majority of church members, church historians sometimes tend to make male clergy and male-only archives (councils, denominational bodies, church records) the voice of the church. Her focus on the leadership and work of Nannie Helen Burroughs “reveal the feminine presence as both a spiritual and political force within the black community” (142). Looking beyond the sources traditionally considered central to the study of Christianity provides a fuller and more vibrant picture of the experiences of Christians—including women.

If we believe women have always had voices, how do we listen anew? Not all voices are recorded in sermons or commentaries or treatises, but in glimpses of boldness in French consistory records, in a quilted representation of Moses raising the bronze serpent, in the tireless leadership of Burroughs, and depictions of women engaged with the early church on the walls of catacombs show us the generations of women who have experienced, contributed to, lead, and shaped Christianity throughout the millennia. Let us listen well, let us listen carefully, and let us listen with a willingness to learn from generations of women who have always had a voice.