I have been writing a chapter on the history of Baptists in Latin America for the Oxford Handbook of Baptist studies. It has been interesting to trace some limitations on what has been written about the group. It is a complex history, being multilingual, multinational, multiracial, multicultural, and multidirectional. Yet, historians often compiled the history of Baptists in the region in volumes that suggest that Baptist groups located in radically different places shared one bounded identity. Historians of Latin American Baptists also generally characterized the entire region by extrapolating limited, localized examples or created encyclopedic narratives that listed a separate Baptist history for each Latin American country without recognizing major themes that generally apply to the entire region. Unsurprisingly, most accounts in English are narrated either by historians without sustained experiential knowledge of Latin American cultures and languages or by missionaries and former missionaries often quick to praise denominational accomplishments at the expense of narrating the full complexity of Baptist histories in the region.

Even though post-Civil Rights developments nudged Baptist historians in the English-speaking world to be increasingly critical, historians of Baptists in Latin America have, by and large, engaged in a self-congratulatory mode of history writing. Thus the primary goals and central functions of most published histories of Baptists in Latin America have been to celebrate Baptist missionary success and the connected locally-led growth among Baptists in the region, not to provide critical historical accounts of the group.

In confessional-friendly accounts of evangelicals in Latin America (and evangelicals in general)—even recent scholarly ones—one struggles to find the recognition that Protestant missions were part of the apparatus that helped shape local Christians in ways that resembled more traditional forms of colonialism, despite sporadic examples of contextual adaptations. Nevertheless, Baptists from Europe and the United States were among the most successful implementers of a neo-colonial order. Locals were often enthusiastic about entering into an imagination commonly introduced by White foreign missionaries. As Baptist projects attained qualified success, missionaries wrote histories of their conquests in Latin America. However, Baptist historians, missionaries or not, have generally reproduced a context in which only rarely have non-Whites produced broadly distributed accounts of Baptists in the region in English.

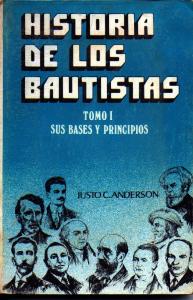

White missionaries nevertheless recognized the unique nature of Latin American Baptist history. For example, former missionary Justice C. Anderson stated in the first sentence of his respectable attempt to narrate the history of Baptists in Latin America that “Baptists and other Evangelicals in Latin America have a history of their own!”[1] Robert E. Johnson, also a former missionary, recognized at the beginning of his attempt to write about Baptists worldwide that “because the dominant interpreters of the Baptist story have been Anglo, the history of the movement has tended to develop mostly along the lines of Anglo cultural themes.” [2] Indeed, those observations are as appropriate as they are paradoxical. Anderson and Johnson—and others—represent the predominant mode in which the histories of Baptists in Latin America are told and preserved.

On the one hand, White, USA- and Europe-based historians—many missionaries, former missionaries, or adopters of denominational optimism—have been the boldest manufacturers and proclaimers of Baptist history outside the confines of their originating cultures, languages, and ethnicities. White historians from the English-speaking world, on the other hand, have also contributed to the narrative of Latin American Christianity, both via their scholarship as well via their support for a new generation of academics from Latin America who are presumably able to offer histories more solidly grounded on experiential knowledge (while nonetheless using the symbols that gatekeepers of Anglo-dominated modes of knowledge production deem respectable). Nevertheless, the colonial anxieties of many Baptists in the U.S. and Europe, often ready to celebrate Baptist global epistemological conquests via unproblematic historical narratives, are palpable in many accounts of “global Baptist history.” While the contributions of such scholarship are as undeniable as their presence is inescapable, they often obscure how successful Anglo Baptists have been in imposing their theocultural norms abroad via diversified means and in ways often profoundly problematic. As a result, the history of Baptists in Latin America has often been narrated in uncritical accounts about alleged heroes (local denominational leaders and foreign missionaries the greatest among them), numeric growth, and institutional accomplishments.

The published histories of Baptists in Latin America available in Spanish and Portuguese—even when written by locals—also generally fit this mold. The careers and livelihoods of Latin American locals who attempted to write Baptist history were often directly or indirectly dependent on missionary and denominational agencies not interested in denominational soul searching. These locals, by and large, shared the denominational optimism of their missionary mentors, overseers, and funders. These histories need decolonization, and critical accounts of the group are still rare in English and other colonial languages broadly spoken in Latin America, such as Spanish and Portuguese. Latin American Baptist historians trained in the United States and Europe, like those trained in their countries of origin or in Baptist institutions intended to be regional training centers, did not commonly develop different approaches.

The shared tendencies demonstrated in Baptist history in Latin America and the Global North context are a testament to the global power of Baptist ideological formation and other powerful denominational constraints—constraints disseminated and reinforced by knowledge production systems and broader communication networks. As Argentinian Baptist theologian Nicolás Panotto has argued, the “colonial matrix” in theological education in Latin America continues to guide how denominational leaders are formed. It is a “colonial matrix” that is manifested via “the presence of traditional curricula and a strong presence of themes that belong to Christian traditions, academic and philosophical, that are not necessarily related to the religious, ecclesial, and social context of our region.” [3] Such a “colonial matrix” is at the heart of how the history of Latin American Baptists is often told. In my chapter for the new Oxford Handbook of Baptist Studies, I am trying to remedy some of these limitations plaguing Latin American denominational history.

[1] See Justice C. Anderson, An Evangelical Saga: Baptists and their Precursors in Latin America (Maitland: Xulon Press, 2005).

[2] See Robert E. Johnson, A Global Introduction to Baptist Churches (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[3] See Nicolas Panotto, Descolonizar o Saber Teológico na América Latina: Religião, Educação e Teologia em Chaves Pós-Coloniais (São Paulo: Editora Recriar, 2019)