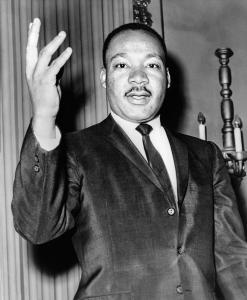

In the wake of the murder of Tyre Nichols and the continuing waves of violence in the world and in our communities, I regularly return to the ethical and political question of violence. I’ll go into more detail about this in my forthcoming book with Brazos Press (keep an eye out for Children of Mammon!) and I discuss it on my podcast, but it is important to note that my reflections were reshaped last year by a re-engagement with Martin Luther King Jr.’s complete legacy. This included not only a devotion to resistance against the three evils (white supremacy, capitalist exploitation, and militarism) but also a principled and consistent nonviolence.

One could argue that his ethic of nonviolence drove all of his actions. But before I get into the specifics, one thing must be said about real, thoroughgoing nonviolence: it is an extremely, extremely difficult position to consistently hold and King did. Malcolm X and others thought it was ridiculous. Malcolm, my namesake, would say,

There is nothing in our book, the Koran, that teaches us to suffer peacefully. Our religion teaches us to be intelligent. Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone; but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery. That’s a good religion. In fact, that’s that old-time religion. That’s the one that Ma and Pa used to talk about: an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth, and a head for a head, and a life for a life. That’s a good religion. And nobody resents that kind of religion being taught but a wolf, who intends to make you his meal.

That sounded reasonable to most people and it sounds reasonable today. If someone is beating up on you, you fight back, preferably with a punch to the throat. Not so with King.

But this is also why it is profoundly tone deaf and unkind to respond to someone who is suffering, “Well, just respond nonviolently.” That is not easy. At all. Remember that when or if you witness riots or violent protests against injustice. Of course there are some who are just rabble-rousers, but there are others who are sincerely at the end of their rope. There is also another level of discomfort when one considers the phenomenon of white people critiquing the violent responses of Black people to their own oppression and marginalization, when it is clear that the former have not put in the work to understand the agony of that marginalization. Centuries of brutal physical, economic, educational, and emotional violence offer a pretty significant base from which to respond in kind. In fact, according to a particular logic, it appears to be the most reasonable response. And yet…

King was devoted to nonviolence first and foremost because of his faith in Christ. He was deeply convinced that it was the Lord’s intention for his people so it was the message he preached. He summarized nonviolence as an ethic into the following six points:

1: Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people. It is active nonviolent resistance to evil. It is aggressive spiritually, mentally, and emotionally.

2: Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding. The result of nonviolence is redemption and reconciliation.

3: Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice, not people. Nonviolence recognizes that evildoers are also victims and are not evil people. The nonviolent resister seeks to defeat evil, not people.

4: Nonviolence holds that suffering can educate and transform. Nonviolence accepts suffering without retaliation. Unearned suffering is redemptive and has tremendous education and transforming possibilities.

5. Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate. Nonviolence resists violence of the spirit as well as the body. Nonviolent love is spontaneous, unmotivated, unselfish and creative.

6. Nonviolence believes that the universe is on the side of justice. The nonviolent resister has deep faith that justice will eventually win. Nonviolence believes that God is a God of justice.

When you hear these principles, one thing ought to strike you: this seems like it would be impossible for someone if they aren’t a Christian. And at that, you recognize both the brilliance and the difficulty of truly being an heir to King’s legacy. It requires much more than just the ability to repeat a quote. It requires your whole self. It requires a trust in a Savior who will win even if you lose. It requires trust in a God who will bring justice even if you die in the struggle. That takes courage indeed. But it is, I believe, what Christ calls us to and has given us His Spirit to do: to truly carry on the legacy of Dr. King, recognize the radical, arm yourself against the triple evils, and live a life of nonviolence. It is clear then that Dr. King is not calling us to some kind of saccharinely sweet colorblindness in which we act as though we “don’t see color” as the goal. Instead, he calls us to a profound race-consciousness, one that demands that we give our neighbor their due, especially if they have been consistently denied it. A commitment to racial justice is first and foremost a commitment to healing, particularly the healing of wounds.

My favorite quote from Malcolm X is this: in 1965, he was asked whether he had seen progress. His response:

No. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six, that’s not progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even pulled the knife out much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit that the knife is there.

If the history of white supremacy teaches us anything, it is a history of death, whether we look at the Middle Passage, the massive industry of human and sex trafficking that racialized chattel slavery was, convict leasing after the Civil War, lynching, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, or police violence today. If we are to be ministers of life, it requires us to seek not just improvement, but equality.