A crisis occurred in Mansfield, Texas, during the fall of 1956. A typical Jim Crow town in the South, Mansfield had numerous “separate but equal” laws for its black citizens. 1950s Mansfield had a population of approximately 1,500 citizens, with 350 of them estimated to be black. These black citizens’ residences were segregated to the West side of town.[1] The only church that permitted black attendance in Mansfield was the all black, Bethlehem Baptist Church. Blacks were required to enter the rear of local grocers, and they sat in the balcony of the local movie theater. Many areas of town were designated as white only areas, and when black people loitered in those areas, white police excessively harassed and harangued them.

Black students attended “Mansfield Color School” up to 9th grade, which were “two long shabby barracks-style buildings placed lengthwise, side-by-side.”[2] Once black students entered high school they had to bus themselves to the only high school that permitted black students, I. M. Terrel High School in Ft. Worth. This required them to wake before the sun rose in the morning and embark on the Continental Trailways bus to Ft. Worth, followed by either walking to the school or boarding another bus to Terrel High School. They would have to do this again at the end of the school day, frequently arriving home after the sun had set. One woman reported that her brothers were commonly away from home for twelve hours a day, due to the 36–40 mile round-trip travel to and from school.[3]

Like the rest of the schools in the nation, Mansfield schools were expected to integrate black students following the pivotal civil rights ruling of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Yet, white citizens in Mansfield were reticent to conform to federal law. Through the efforts of local black citizens, and in partnership with the local chapter of the NAACP, Mansfield High School was the first school in our nation to receive a federal court order to integrate.

After an extensive fight in the courts, a class action suit of students finally won an appeal, with not much time to spare, before school registration later that month. The August 17, 1956 mandate of the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in the case of Jackson v. Rawdon stated:

Nathaniel Jackson, Charles Moody, and Floyd Stevenson Moody, and all other negro minors of the same class as the named minor plaintiffs, have the right to admission to, and to attend the Mansfield High School on the same basis as members of the white race, and that the refusal of the defendants to admit plaintiffs thereto on account of color or race is unlawful.[4]

However, white citizens in Mansfield were not having it, and they were not going to desegregate without a fight. Their militant and mob resistance to federal law led to events historians now call “The Mansfield Crisis.”

Instead of integrating their high school, these citizens decided to take advantage of the visual function of the high school flagpole and send a message to students expecting to integrate. Typically, the school flagpole hoists the most powerful symbol of our nation, the Stars and Stripes. We give our allegiance to this symbol and when our national flags fly high, in front of our public schools, we feel national pride, peace, and safety.

However, white citizens, during August and September of 1956, twisted the function of their high school flagpole into a nefarious use, as a venue for a hateful, racist, and white supremacist message, employed to instill fear and intimidation in the students who attempted to integrate into Mansfield High School.

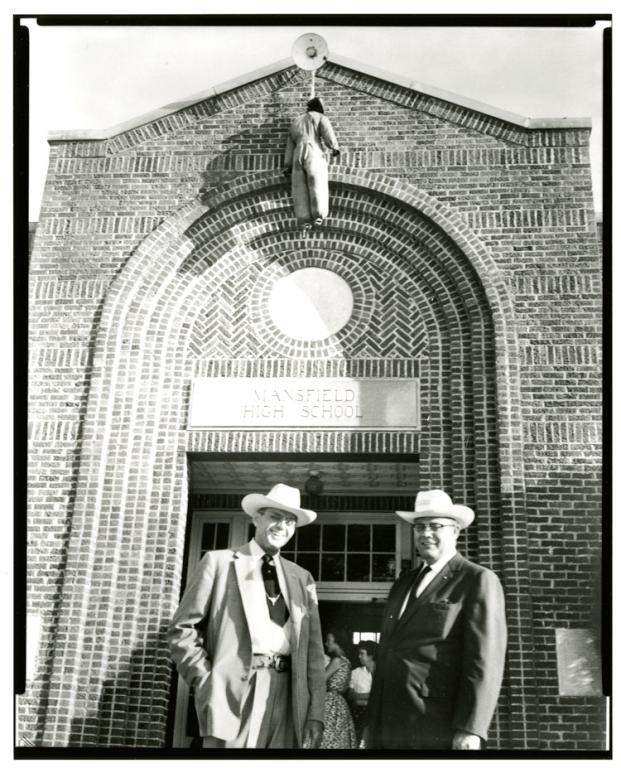

Early in the morning on August 30, young white high school students hoisted up the school flagpole an effigy of a black man hanging from a noose. The day prior, another effigy had already appeared, hanging from wires in the downtown area of Main Street, Mansfield. This straw-stuffed effigy had red paint splattered on it, with a sign hanging from its feet. Students went on to hang a third effigy over the entrance to the school, painted a car with racial slurs, and parked it nearby the school.

“Mac” Moody later reported that the downtown effigy was directed to T. M. Moody, one of the black activists involved in School Board Meetings and the Jackson v. Rawdon court case leading up to the attempted school registration and integration day for the 1956–57 school year.[5]

These effigies sent a clear threat to any black student who wished to register for school that day and any activists or advocates supporting their cause. The effigies continued to hang until the first day of school on September 5.

During this time, Governor Allan Shivers commissioned Texas Rangers to keep the peace in Mansfield and “stop any threat of violence” while the 200–500 white, mob of students, parents, and concerned neighbors gathered with dogs and shotguns to prevent black students from registering or attending high school that week.[6]

KXAS reported that one man appeared on the scene, claiming to be “Jesus Christ,” and offered to replace the effigy with the U. S. flag. School officials and lawmen refused to give him permission, and when he departed Ranger Captain Crowder sent men “to see that he doesn’t return.” Later that same day, an episcopal priest arrived, appealing for the people to disburse, saying “God calls man to love his neighbor.” The appeals of Reverend D. W. Clark, vicar of St. Timothy’s Church in Ft Worth, arose the ire of the mob, and so Ranger Sergeant Banks escorted the priest away from the crowd.[7]

Needless to say, despite the federal court order, no black students registered or attended Mansfield High School that year. In fact, the first black students to attend Mansfield High did not do so for nearly another decade, not until the 1965–66 academic year.

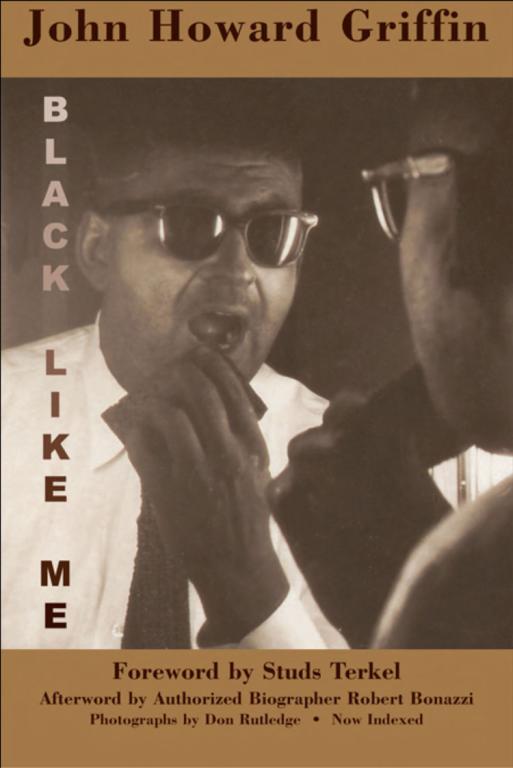

During the intercalation between the first integration attempt in 1956 and the successful one in 1965, John Howard Griffin wrote his account, Black Like Me. Griffin, a Mansfield citizen, altered the color of his skin, from white to black, in order to understand the situation of black citizens in the South. He wrote:

How else except by becoming a Negro could a white man hope to learn the truth? Though we lived side by side throughout the South, communication between the two races had simply ceased to exist. Neither really knew what went on with those of the other race. The Southern Negro will not tell the white man the truth. He long ago learned that if he speaks a truth unpleasing to the white, the white will make life miserable for him. The only way I could see to bridge the gap between us was to become a Negro. I decided I would do this.[8]

I never learned the history of “The Mansfield Crisis” nor was required to read Black Like Me during my K–12 experience in Mansfield public schools’ first-rate education. I only discovered this history about my hometown during the last couple years of historical studies. I think it’s the sort of history that the State of Texas and its governing authorities would like to erase from the historical record. Perhaps this history is precisely what current Texas authorities wish to censure from classrooms.

Nonetheless, “The Mansfield crisis” is part of the memory and the context that is critical for considering the intersection of Christian Nationalism and Evangelicalism. I don’t think we really have to pose the question, “Were evangelicals among the mob in Mansfield?” Undoubtedly, they were present and active that day, which is misfortunate, for it is going to be in the same space, the school yard out front of the public high school and at the foot of its flagpole, that white evangelicals are going to stage a student led, prayer driven, spiritual war and revival movement during the 1990s. And Mansfield, Texas sits near the epicenter of the making of the movement for flagpole prayer known as See You at the Pole.

[1] Oral history interview with Jossie Brooks, “On West Side of Mansfield,” UNT Oral History Program, accessed January 29, 2024, https://omeka.library.unt.edu/s/the-crisis-at-mansfield/item/3424.

[2] Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools, 6.

[3] Oral history interview with journalist Bob Ray Sanders, “Benevolent Racism,” Texas Communities Oral History Project, accessed January 29, 2024, https://crbb.tcu.edu/clips/69/benevolent-racism; See “Jackson v. Rawdon – November 21, 1955 – Explanation by Judge Estes,” The Crisis at Mansfield, accessed January 30, 2024, https://mansfieldcrisis.omeka.net/items/show/329.

[4] “Jackson v. Rawdon – US Court of Appeals – Mandate,” The Crisis at Mansfield, accessed January 30, 2024, https://mansfieldcrisis.omeka.net/items/show/310.

[5] A typescript oral history from “Mac” Moody reports that the downtown effigy was directed to T. M. Moody, “Mansfield African American Oral History Project, T.M. Moody discussion,” The Crisis at Mansfield, accessed January 30, 2024, https://mansfieldcrisis.omeka.net/items/show/247.

[6] “Mansfield High School: Texas Rangers, Students, and Effigy,” Texas State and Library and Archives Commission, accessed on January 29, 2024, https://mansfieldcrisis.omeka.net/items/show/7.

[7] KXAS News Script: “Mansfield School Opens,” UNT Special Collections, KXAS-TV/NBC-5, Fort Worth, TX, September 4, 1956, accessed January 29, 2024, https://mansfieldcrisis.omeka.net/items/show/149.

[8] John Howard Griffin, Black Like Me, 2.