“I want an honest recollection of what has been done. I want a reckoning with the harm purity culture has caused so many people. Not because I have a vendetta against evangelicals (to be clear, I don’t), but because I see the disparity between my faith and the ideas purported by purity culture.” I recently expressed this sentiment to an interdisciplinary group of scholars. We were reflecting on the ways we envision our scholarship having an impact on society. I then asked of myself and my colleagues, “But is that enough? Is it enough to write what has been done?”

Historians, while debating the ways their present moment influences their scholarship, often avoid offering solutions to the realities to which history attunes us. We might hope that readers of our work are more clear-eyed about the past and have a sense of how we got here in the aftermath of wrestling with difficult histories. Yet, after setting aside history books, readers are often still fuzzy on where they go from here. How might they chart a path forward?

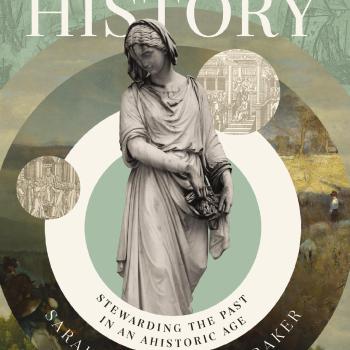

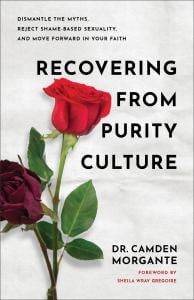

It is this question that Dr. Camden Morgante, a licensed psychologist, begins to answer in Recovering from Purity Culture: Dismantle the Myths, Reject Shame-Based Sexuality, and Move Forward in Your Faith (2024).[1] Dr. Morgante sections her book into three parts. The first provides an overview of the development of purity culture in all its metaphors and the impact it has on both faith and sexuality. In the second, Morgante identifies five central purity culture myths. They are as follows:

It is this question that Dr. Camden Morgante, a licensed psychologist, begins to answer in Recovering from Purity Culture: Dismantle the Myths, Reject Shame-Based Sexuality, and Move Forward in Your Faith (2024).[1] Dr. Morgante sections her book into three parts. The first provides an overview of the development of purity culture in all its metaphors and the impact it has on both faith and sexuality. In the second, Morgante identifies five central purity culture myths. They are as follows:

- The Spiritual Barometer Myth which asserts that “your worth, identity, and spiritual maturity, especially for women, is your virginity” (41).

- The Fairy-Tale Myth that claims, “if you remain pure, God will bless you with a loving spouse and marriage” (41).

- The Flipped Switch Myth. This myth promises that “your sex life will be instantly pleasurable and satisfying if you wait until marriage” (42).

- The Gatekeepers Myth states that “men are more sexual and can’t control themselves, therefore it is up to women to enforce boundaries before marriage and meet their husband’s sexual needs after marriage” (42).

- The Damaged Goods Myth: “If you have premarital sex, you are broken and damaged” (42).

Finally, Morgante suggests steps for readers’ reconstruction of their faith and a sexual ethic devoid of shame. She writes of her own path forward, “I needed two things: a more robust sexual ethic and a more robust faith” (19). It’s the latter I’d like to focus on today.

The book fills an important gap in the literature on purity culture—it is written both by and to people who attempt to detach purity culture from their faith, losing the former but holding fast to the latter. I had to chance to interview Dr. Morgante about her book and when asked what she most hoped readers would glean, she responded, “The biggest takeaway I wanted readers to have was that you can hold on to your faith and still heal from purity culture—that you don’t have to choose one or the other. There is a way to be a faithful Christian while still acknowledging all the harm that it has done.”[2]

Reckoning With Harm

And Morgante certainly reckons with the damage done. This is important. Historians have highlighted the ways evangelicals marketed purity culture as a liberatory choice for women, particularly young women and girls.[3] Evangelicals argued that women gain a certain sense of independence and agency in refusing men’s gazes and advances. There is power in purity, the story goes. The empowerment myth, if you will. While historians have traced the ways evangelicals have constructed these ideas, Morgante offers a brief view into the reality of the impact of these beliefs.

Examples from her work with clients pepper the narrative. She discusses struggles with sexual dysfunction, pain with sex, and women’s lack of orgasm to name a few. She also offers an entire section dedicated to rape culture’s connection to purity culture. Morgante concludes that purity culture “creates a sense of sexual shame, repression, and anxiety about sex…. Our bodies themselves—and especially our genitals—are the source of our shame. They are sinful, bad, and prone to temptation.” (35)

However, one of her most important contributions is not only to connect purity culture to rape culture, but also to think about purity culture itself as producing trauma responses, even aside from its exacerbation of sexual violence. She writes, “Studies have found that people who come out of purity culture have similar sexual problems as people who have experienced sexual trauma” (35). Morgante follows these revelations with ways to address and manage these trauma responses.

Deconstructing, Not Deconverting

I would guess that for many faithful Christians, fear that they might lose their faith prevents them from turning a critical eye to the myths of purity culture. Yet, as Morgante illuminates, the damage incurred by purity culture involves not only trauma held in our bodies but also holds potential to harm our religion. Morgante writes, “many of us who grew up in purity culture deconstruct because we want to hold on to our faith” (122). Purity culture teaches that its promises regarding “great sex” or marriage are made by God. When these are unfulfilled, questions about God’s faithfulness arises.

In my conversation with Morgante, she stated that she believed she had a unique perspective to offer because she was a person of faith, and she wanted to demonstrate that deconstructing purity culture need not result in deconversion. It might even lead to a deeper understanding of faith. Morgante leaves open the likelihood that changes to our faith will happen: “I don’t want the Christianity I formerly knew—the one that relied on spiritual platitudes, empty promises of sexual prosperity, black-and-white beliefs, and fear judgement, and condemnation of anyone who looks or thinks differently.” (133) Thus, evaluation of purity culture myths and trauma could lead to a more robust faith.

Toward Healing?

Could this deeper faith aid healing? Throughout the book, Morgante is firm that healing is not simply a change in belief. Rather, “To heal from purity culture, we have to get our head, heart, body, and soul aligned” (37). While the book is brimming with pragmatic suggestions, it also seems to me that the act of disentangling and reconstructing our faith encourages this sort of alignment belief, emotion, body, and soul where healing begins to occur.

To be clear, Morgante acknowledges that she addresses healing at an individual level. Purity culture is both individual and systemic, so while the focus of the book is primarily individual, ultimately “we have to pluck out the roots of patriarchy in ourselves and in our systems” (51).

Still, what does it mean to disentangle one’s faith from purity culture? In our conversation, Dr. Morgante stated that part of the process was to extricate the biblical from the cultural. Here, history lays a foundation. In answering “how did we get here” we see cultural constructions taking place—we can identify myths. And there is power in labeling these ideas myths. It involves not simply a change in belief, but the hard work of separating out our faith, or even reconstructing our faith, from purity culture.

Several of Morgante’s chapters follow this outline: (1) Uncovering the Myth; (2) Discovering the Effects; (3) Recovering the Truth. It seems disentangling myths from faith, and potentially reforming our faith in the process involves both deconstruction and reconstruction. Thus, the “how did we get here” and “where do we go from here” might not be so different from one another. Or they at least might be intertwined processes. A reckoning with the history and realities of purity culture aids us in the process of untwining the biblical from the cultural. Here, healing might begin, aided by the more practical tools Dr. Morgante offers. For those, you’ll have to read her book.

Katie Heatherly is a Ph.D. student at the University of Notre Dame where she studies late-twentieth-century evangelical women, gender, and sexuality. Her research centers evangelical sex advice literature and explores questions of positionality, authority, agency, and navigation of patriarchy.

Katie Heatherly is a Ph.D. student at the University of Notre Dame where she studies late-twentieth-century evangelical women, gender, and sexuality. Her research centers evangelical sex advice literature and explores questions of positionality, authority, agency, and navigation of patriarchy.

[1] Camden Morgante, Recovering from Purity Culture: Dismantle the Myths, Reject Shame-Based Sexuality, and Move Forward in Your Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2024).

[2] I interviewed Dr. Morgante on February 6, 2025.

[3] See Sara Moslener, Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence, 1st ed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Amy DeRogatis, Saving Sex: Sexuality and Salvation in American Evangelicalism, 1st ed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014); Christine J. Gardner, Making Chastity Sexy: The Rhetoric of Evangelical Abstinence Campaigns (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).