You can think many things about the Trump presidency, but few devote much attention to the impact on the select band of scholars who work on the history of American empire, people such as, oh, myself. I will explain that concern in this post, and suggest that the apparent weirdness of some of the administration’s current claims have very deep historical roots. He is no Donald-come-lately.

Dreams of US Empire

So here I am innocently writing a book on religion and the US empire throughout the country’s history, a theme on which I have posted on many occasions at this site. Suddenly along comes the 2024 election and the victor starts reviving issues that I thought were neatly consigned to earlier American centuries. Annexing Canada? Greenland? Panama? Suddenly my academic interests are oddly newsworthy.

If we look back at the very earliest years of US history, successive administrations had a number of territorial goals that they regarded as a matter of when, rather than if. These included, first, the national frontier on the Mississippi, and subsequently expansion to the Pacific, but they also, with equally total assurance, included the acquisition of Canada and Cuba. To a degree that seems astonishing in retrospect, if we look at those administrations over a period of something like 150 years, it never occurred to them that those areas would not become part of the American union, eventually, and probably quite soon. I won’t talk about Cuba here since the current president has not yet expressed a desire to annex it (or at least had not as of yesterday).

But Canada… it is still a miracle that the US failed to annex it during the war of 1812, which I like to call the War of Canadian Independence. Had it not been for a brilliant and sneaky British commander named Isaac Brock, the Americans might well have seized the country then. At the Wikipedia entry, do read the account of Brock’s capture of Detroit, and marvel.

THE AMERICANS: We’re going to take Canada! We’re going to take Canada! …. Oh my Lord, we’ve lost Michigan.

American dreams remained potent for over a century after that. When in 1845 John L O’Sullivan popularized the idea of Manifest Destiny, that concept assuredly extended to Canada:

Whatever progress of population there may be in the British Canadas is only for their own early severance of their present colonial relation to the little island three thousand miles across the Atlantic—soon to be followed by annexation and destined to swell the still-accumulating momentum of our progress.

Americans and British long felt that a great war between the two countries, a much larger replay of 1812, was inevitable, and if it did, it would certainly end with the annexation of Canada. (Generals of the quality of Isaac Brock only surface once every millennium or so). Just how steady a theme that was should be stressed. In Herman Melville’s books, especially White-Jacket (1850), we repeatedly get the sense that conflict on the seas was imminent and inevitable. Naval and imperial rivalries made warfare certain, as did U.S.-Canadian border rivalries: frontier disputes in the Oregon territory stirred American war fever in the 1840s.

Between 1840 and 1900, serious war scares were running at about one per decade. Time and again, from the 1860s onward, border-crossing activities by Irish guerrillas threatened to sabotage the fragile U.S.-British modus vivendi. When the two countries yet again came close to war over Venezuela’s borders in the 1890s, the up and coming young Theodore Roosevelt wrote that “I don’t care whether our sea coast cities are bombarded or not, we would take Canada.”

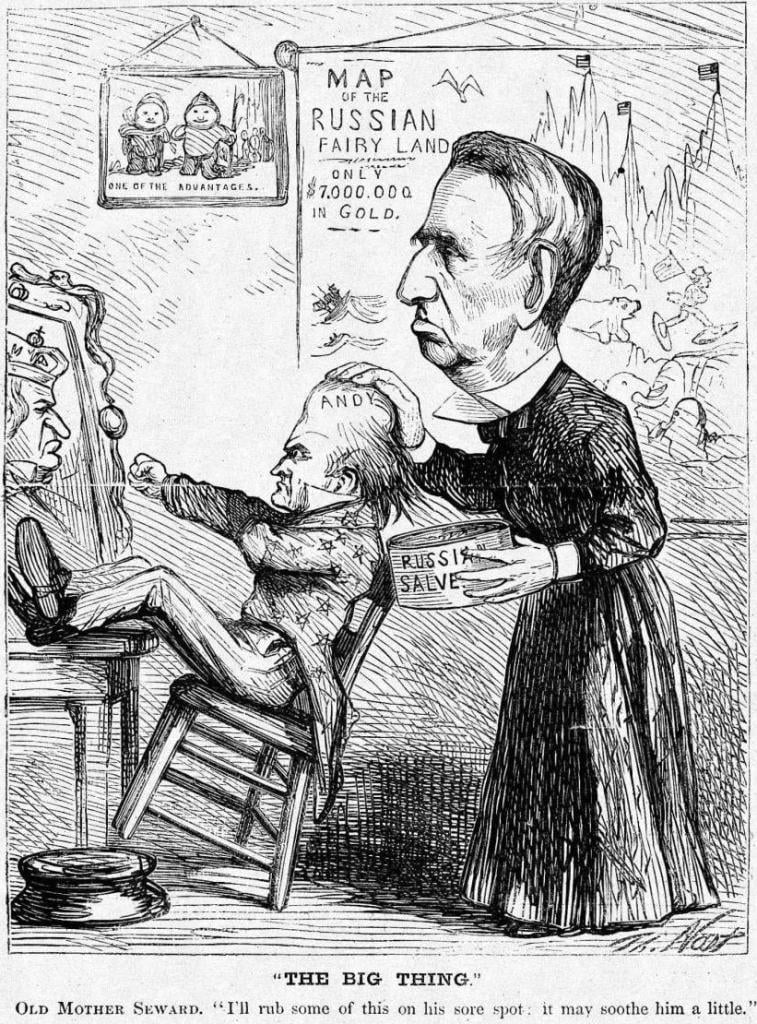

Seward’s Project

In my current book project, I talk a lot about William H. Seward, a US Senator who served as Secretary of State through much of the 1860s. In that role, he was chiefly responsible for the purchase of Alaska (“Mr. Seward’s Icebox”), but his imperial dreams extended to the full acquisition of Haiti and the Dominican Republic as well as Greenland and the Danish West Indies, and he wanted to build a canal roughly in the location of the later Panama Canal.

His visions certainly included acquiring Canada. Seward publicly declared that the whole of North America “shall be, sooner or later, within the magic circle of the American Union,” and he boasted that the new transcontinental railroad potentially opened the whole Canadian West to future American annexation. Seward knew that such advances would provoke conflicts, “the strifes yet to come over ice-bound regions beyond the St. Lawrence and sunburnt plains beneath the tropics.” He also had immense confidence in the very large and battle-hardened US armed forces, fresh from victory in the Civil War.

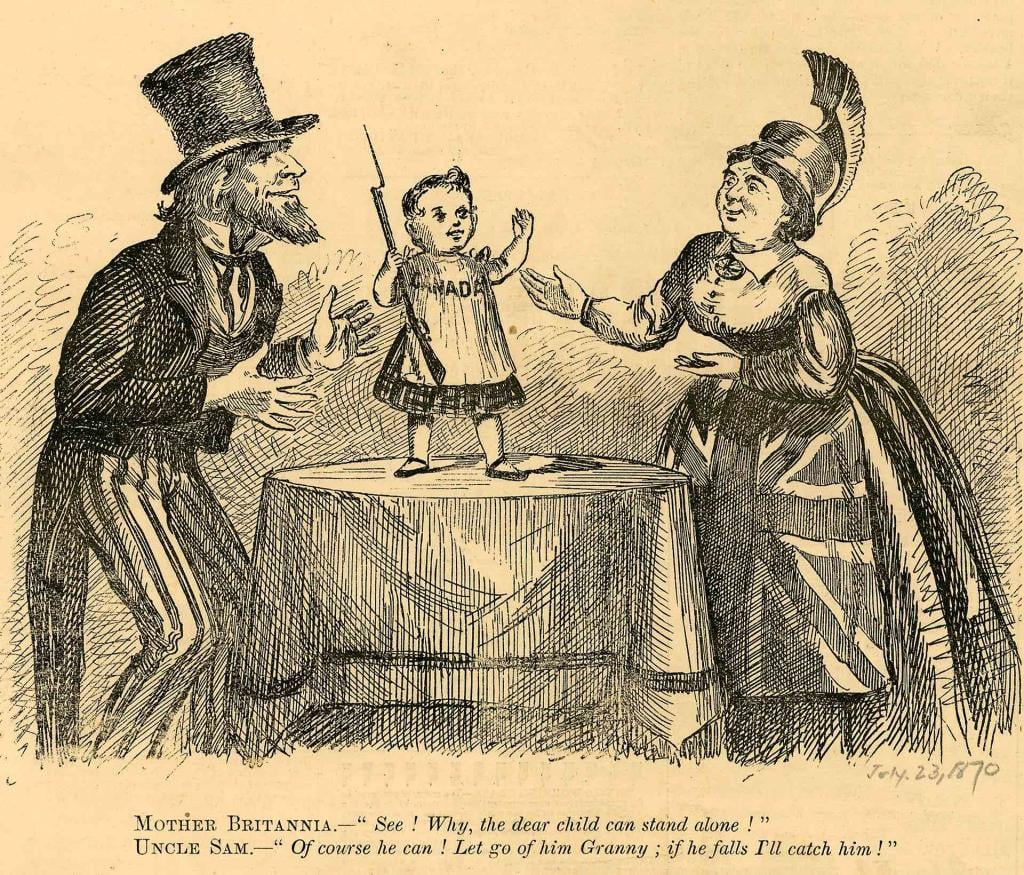

It was in direct response to Seward’s terrifying ambition that the British formed the Confederation, the Dominion of Canada, in 1867. The province of “British Columbia” – that is, British America – dates from 1871.

Although Seward’s ambitions sound wildly excessive, the US would by the first quarter of the twentieth century achieve most of the goals he specified, with only Greenland and Canada remaining beyond the American grasp. The US repeatedly invaded and occupied Haiti and the Dominican Republic (and, of course, dominated Cuba for decades). Those Danish West Indies he mentioned have since 1917 been the US Virgin Islands.

Into a New Century

Only very gradually did Americans come to terms with the fact that the Canadian dream was not to happen. In 1912, Edward House, the leading adviser of the incoming president Woodrow Wilson, published the near-future fantasy Philip Dru, Administrator in which he imagined the natural absorption of Canada into the US.

After the First World War, the US prepared contingency plans for a number of potential future wars, and War Plan Red envisaged an invasion of Canada, and it was specified that no territories conquered in such an operation should ever be returned. US forces planned ultimately to seize Canada’s rich mineral resources around Sudbury, Ontario, but in the interim, they would launch surprise attacks on the key ports of Halifax and Vancouver. While many planners disliked the prospect of using poison gas on civilians, it was essential to knock out those strategic centers swiftly, before the British mounted their inevitable counter-offensive. (American planners confidently expected a British amphibious invasion to land between Ocean City, Maryland, and Rehoboth Beach, Delaware). Those plans remained very much alive into the 1930s.

If such an act of absorption had occurred, the US homeland would have stretched to the Arctic Circle.

Greenland attracted less interest, because it was far less known, but the US did de facto acquire it in 1941, and they retained their influence there long after the immediate crisis of the Second World War had passed.

Blame Canada

Nobody, surely, treats the present American rhetoric about Canada too seriously, or as anything more than a standard Trump tactic of trolling another world leader he dislikes. But for the sake of argument, let us treat these threats at face value. Is there anything Canadians can do to save their country?

Actually, they could and quite easily, by means of creating a simple poison pill. The 51st state? Nonsense. Canada should immediately apply for membership in the United States, with the natural proviso that each of its provinces be accorded equal status with present American states. The ten present provinces would each receive its due allocation of two senators in an expanded US senate that would grow from 100 to 120. No great stretch would be involved in requesting a comparable status for the three present territories, increasing the size of the Senate to 126 in all. The chair recognizes the gentleman from New Brunswick. Or Nunavut…

This would give Canada roughly twenty percent of the new US senate, and if they built their coalitions carefully, a near stranglehold on all future legislation for Greater North America. Now THAT is a power bloc, and the consequences would soon be felt. The exact scheduling of legislation on national/continental French bilingualism would be a matter for early decision. So would a likely restructuring of the NHL. And maybe redating Thanksgiving. And more weightily, don’t get me started on the implications for the legal position of Native peoples/First Nations across the whole continent.

Who exactly would be annexing whom?

I think Canada is safe for a good few decades yet.

On another very current foreign policy issue, all continuing respect to Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who since 2022 has heroically personified the moral and political values of the West. Don’t let anyone tell you different.