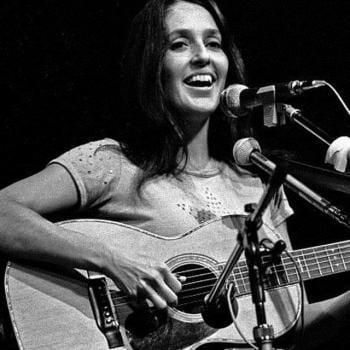

The song “Deportee” came on my radar researching folk singer Joan Baez’s support of Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers (UFW). She publicly performed the song at the memorial service for murdered farmworker Juan De La Cruz. This footage is from the documentary Fighting For Our Lives about the 1973 strike and labor battle with the Teamsters’ union. Baez’s music closes the documentary. In fact, “Deportee” appeared as a special accompanying album with her album Blessed Are… that came out in 1971. It was dedicated to the farmworkers across the world and to their struggles.

A quick search on Spotify shows that the song has been performed by music legends like Bruce Springsteen, Dolly Parton, Judy Collins, Joni Mitchell, The Byrds, and The Highwaymen (Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, and Johnny Cash). Where did this song come from and what is it about? The subtitle “Place Wreck at Los Gatos” provides some clues.

In 1948, a plane carrying 32 people crashed in California, 20 miles west of Coalinga. It is considered the worst plane crash in California’s history. 28 people were undocumented and being flown to Mexico instead of the usual route on land. They were unnamed in the original news reports—referred to as deportees. What remains they could find would be buried together in a mass grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno, California. Folk legend Woody Guthrie was enraged that the Mexican passengers were left unnamed. The erasure of the victims resulted in Guthrie’s lyrics.

Tim Z. Hernandez’s book All They Will Call You was written in response to the song. The song was how he found out about the event, what he calls his “beacon” (Hernandez, 193). I owned the book for a couple of years now and had a couple of false starts—for some reason I just could not get into it. Bookmark in, bookmark out. My research on Baez spurred me to take the book with me on a recent road trip up to Sacramento. Perhaps I needed to be somewhat geographically close to the events that I finally dived into the book and read it over that weekend.

Hernandez would seek out one of the other legendary folk singers, Pete Seeger, to find out more about the song (Hernandez, 193-201). He is on record as being the first to sing the song. Seeger would reveal that a young school teacher, Martin Hoffman, created the melody. And the rest is music history.

Hernandez journeyed anywhere the records would take him to find anyone with a connection to any of the 32 people who died in the crash. He travels throughout California and Mexico to talk to anyone who could share the stories of the dead—family members, lost lovers, former braceros, and neighbors among other intimates. Many of the people interviewed were very old. Some of the people had also trekked back and forth from Mexico to California to work. The main chapters include pictures of the subjects, adding faces to their stories. Hernandez’s research resulted in the correcting of the narrative and providing a list of all the people who died. And now we have some of the stories of these people once lost to history.

Hernandez’s book is a wonderful example of history, music, art, journalism, oral history, politics, and cultural studies all rolled up into one—an interdisciplinary literary gem. Imagine teaching this history to students. You can have the students look at the primary sources of the original news articles, and the different iterations of Guthrie’s song. Then they could listen to a selection of the song by various artists. You might reflect on the biblical and ethical implications laid out in the song that interprets this history. The UFW has many documentaries like the one from the 1973 strike that can be viewed, especially with Baez’s performance of “Deportee.” Finally, they could read selections from Hernandez’s book (or the whole book).

The lyrics of the song are especially poignant:

We died in your hills and we died in your deserts

We died in your valleys we died on your plains

We died ‘neath your trees and we died in your bushes

Both sides of the river we died just the same

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye Rosalita

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria

You won’t have a name when you ride the big airplane

All they will call you will be deportees

Some of us are illegal, and others not wanted

Our work contract’s out and we have to move on

But it’s six hundred miles to that Mexican border

They chase us like outlaws, like rustlers, like thieves

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye Rosalita

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria

You won’t have a name when you ride the big airplane

All they will call you will be deportees

While Hernandez discovered this event through the song, my route was through Baez at this UFW memorial at the end of the summer of 1973. Since the song is called “Deportee” there is some tension with the fact that it was at Chavez’s UFW event. Even though Chavez is often considered a Mexican American icon, his history regarding undocumented workers is, at the very least, spotty (Mario García’s biography about Father Luis Olivares shows some growth in Chavez’s life on this matter). Still, while serving a stint in the U.S. navy, when a young Chavez heard of this tragedy he thought that it was a job of somebody to insist that Mexican farmworkers are “as important human beings and not as agricultural implements.”

Baez would commemorate the 70th anniversary of the plane crash in 2018 at the state capitol in Sacramento. After seventy long years, the California government formally recognized this tragic event. It is inspiring to see a book help lead to this public acknowledgment. Hernandez declares: “A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it” (Hernandez, 200). Let me close this post with a duet of “Deportee” sung by Baez and Bob Dylan. At least we can count on folk singers to continue to tell the story, telling us what is wrong and how to fix it.