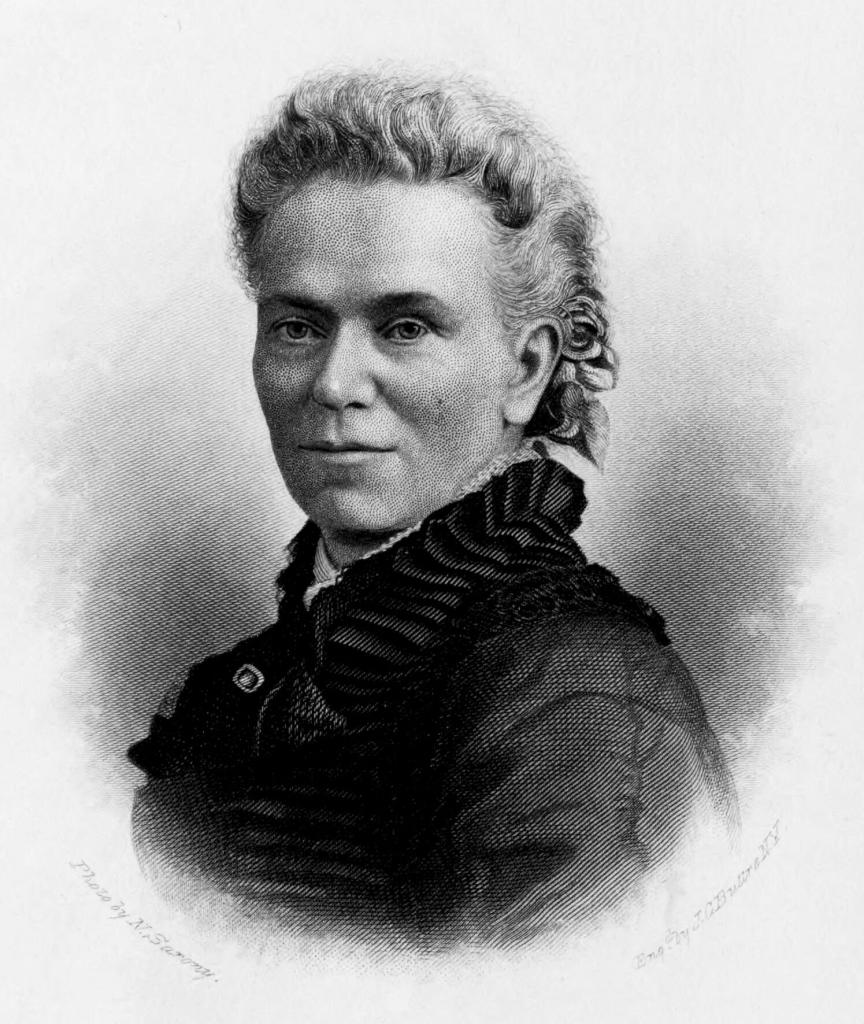

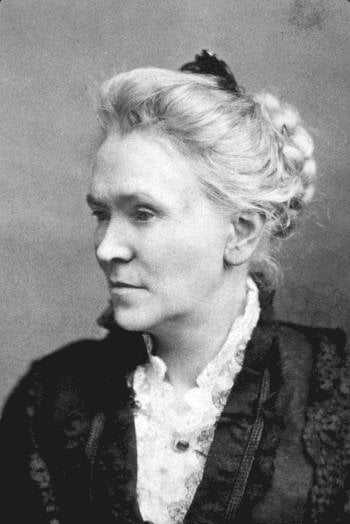

I have been describing the cultural and spiritual transformations that occurred in the United States in the critical year of 1893. These include the US encounter with Global Faiths in the World Parliament of Religions, and the popular discovery of Biblical Higher Criticism during the heresy trial of scholar Charles August Briggs. Today I want to talk about what was arguably a still more important theme that was epitomized by a book that appeared in that year, namely Woman, Church and State, by Matilda Joslyn Gage (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Company, 1893).

All images here are public domain, and drawn from wikipedia sites

All images here are public domain, and drawn from wikipedia sites

The book is famous and is often discussed, but I still think it is underappreciated. Every generation tends to think it has discovered some things for itself as shocking and radical, when often it is just rediscovering the insights of much earlier times. In that one book, Woman, Church and State offers elaborate and highly developed theories about women’s spirituality, about feminist interpretations of the gospels and of early Christian history, and of witchcraft as a historical vehicle of women’s social and spiritual dissent; and so much more. It is “Dedicated to all Christian women and men, of whatever creed or name who, bound by Church or State, have not dared to Think for Themselves.” It all sounds very much indeed like the supposed discoveries of the women’s movement in the 1970s, does it not? You find new treasures every time you venture into the book.

If Woman, Church and State had been the only landmark in American religion in 1893 (it wasn’t), it would alone mark that year as a crucial turning point.

The Divine Feminine

Gage enjoyed a long and distinguished career as an activist, feminist and reformer. For present purposes, Woman, Church and State argues that primitive society was matriarchal, centered on the worship of the divine feminine. The evidence for that fact derived from ethnographic evidence from around the world, together with records of ancient civilizations. Subsequent history represents a prolonged effort by men to suppress that basic truth, and to use religion as a tool for oppressing women, often with brutal violence.

I have contextualized her together with some other feminists of the day who struggled to reinterpret early Christianity as a mystical and egalitarian movement that was also very open to other global faiths: I think of Helena Blavatsky and Frances Swiney. Gage was an early member of the Theosophical Society, an association that she described as the “crown blessing” of her life. One of her recruits into the movement was her son-in-law L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz, among many other titles. Gage also collaborated in The Woman’s Bible coordinated by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, which appeared in 1895. (That very radical book severely divided the movement for women’s political rights).

Lost Gospels

Woman, Church and State offers a revisionist history of Christian origins that sounds precisely as if it could have come from the 1970s. It seeks to go beyond the four canonical gospels to retrieve what she understands as the suppressed truths of the alternative scriptures that had so regularly and sensationally come to light during the nineteenth century. Exactly like a scholar of the 1970s, she argues that the allegedly heretical “Gnostics” were in reality the heroic custodians of those truths:

The androgynous theory of primal man found many supporters, the separation into two beings having been brought about by sensual desire. …. One of the most revered ancient Scriptures, The Gospel According to the Hebrews, which was in use as late as the second century of the Christian era, taught the equality of the feminine in the Godhead; also that daughters should inherit with sons. Thirty-three fragments of this Gospel have recently been discovered. The fact remains undeniable that at the advent of Christ, a recognition of the feminine element in the divinity had not entirely died out from general belief, the earliest and lost books of the New Testament teaching this doctrine, the whole confirmed by the account of the birth and baptism of Jesus, the Holy Spirit, the feminine creative force, playing the most important part.

It was however but a short period before the church through Canons and Decrees, as well as apostolic and private teaching, denied the femininity of the Divine equally with the divinity of the feminine. There is however abundant proof that even under but partial recognition of the feminine principle as entering in the divinity, woman was officially recognized in the early services of the church, being ordained to the ministry, officiating as deacons, administering the act of baptism, dispensing the sacrament, interpreting doctrines and founding sects which received their names.

For a modern readership accustomed to the major streams of scholarship, this all sounds utterly familiar and even commonplace, and it is difficult to imagine how explosive it was in 1893.

I do not intend this remark to demean either person, but I sometimes believe that Matilda Joslyn Gage decided to pursue her career after death and reincarnated as Elaine Pagels.

Witches as Insurgent Women

Woman, Church and State is a very substantial work of 180,000 words, of which just one chapter concerns Witchcraft. However, this single chapter constitutes 25,000 words, and it could easily have been amplified into a book in its own right.

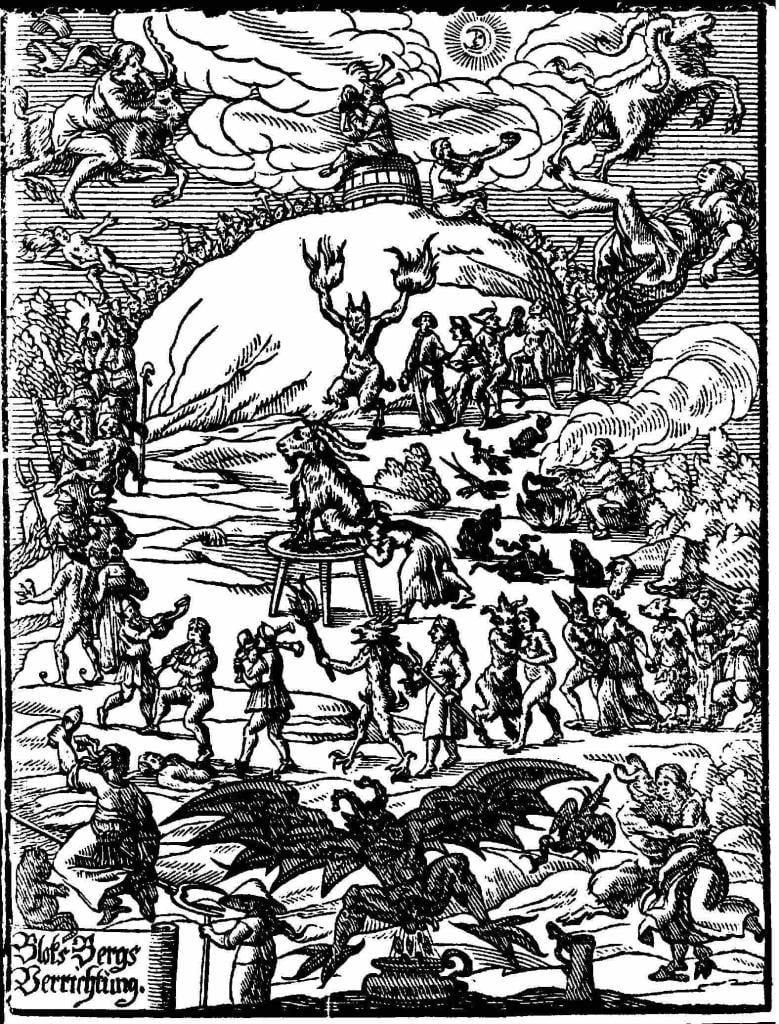

In my last blog, I suggested that the events of 1893 very closely foreshadowed the Fundamentalist / Modernist controversies that “as everybody knows” took place in the 1920s. Something similar happens with Woman, Church and State, which is a generation ahead of its time in its particular topics. By way of context, “everybody knows” that in 1921, British Egyptologist Margaret Murray wrote the book The Witch Cult in Western Europe, which cast its influence over basically all scholarly and popular writing on witchcraft into the 1970s and beyond. For Murray, witchcraft represented an authentic survival of an ancient pagan cult focused on the worship of the Goddess. Our accounts of the witch trials were recording real deeds by real people. If you believed that – and most people did, for about half a century – then for some 1500 years European Christianity coexisted unhappily with a pagan Goddess cult. The Witches’ Sabbat was a very real thing, with its blasphemous parodies of Christian ritual.

Those ideas were not wholly new to Murray. In 1862, Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière argued that witchcraft cults genuinely had existed in bygone Europe, and that they represented thoroughly justifiable insurgencies against social and gender oppression, including sexual violence. But Woman, Church and State takes these arguments much further, and really offers most or nearly all of the arguments that made Murray a global celebrity in the 1920s.

In 1893, Gage had likewise suggested that perhaps insurgent peasants really had held ritualistic gatherings where they denounced the evils of patriarchy and aristocracy, complete with bitter parodies of orthodoxy:

a peculiar and silent rebellion against both church and state took place among the peasantry of Europe, who assembled in the seclusion of night and the forest, their only place of safety in which to speak of their wrongs. Freedom for the peasant was found only at night. … Here with wives and daughters, they met to talk over the gross outrages perpetrated upon them. Out of their foul wrongs grew the sacrifice of the “Black Mass” with women as officiating priestess, in which the rites of the church were travestied in solemn mockery, and defiance cast at that heaven which permitted the priest and the lord alike to trample upon all the sacred rights of womanhood, in the name of religion and law.

…

From these assemblages known as “Sabbat” or “the Sabbath” from the old Pagan midsummer-day sacrifice to “Bacchus Sabiesa” rose the belief in the “Witches Sabbath,” which for several hundred years formed a source of accusation against women, sending tens of thousands to most horrible deaths. The thirteenth century was about the central period of this rebellion of the serfs against God and the church when they drank each other’s blood as a sacrament, while secretly speaking of their oppression. The officiating priestess was usually about thirty years old, having experienced all the wrongs that woman suffered under church and state. She was entitled “The Elder” yet in defiance of that God to whom the serfs under church teaching ascribed all their wrongs, she was also called “The Devil’s Bride.”

This period was especially that of woman’s rebellion against the existing order of religion and government in both church and state. While man was connected with her in these ceremonies as father, husband, brother, yet all accounts show that to woman as the most deeply wronged, was accorded all authority. Without her, no man was admitted to this celebration, which took place in the seclusion of the forest and under the utmost secrecy. Offerings were made to the latest dead and the most newly born of the district, and defiance hurled against that God to whose injustice the church had taught woman that all her wrongs were due.

Witchcraft was genuine, and it was outright feminist insurgency. What exactly was Murray saying that Gage had not already argued?

Feminist Visions of Witchcraft

Beyond her role as a precursor of Margaret Murray, Gage also makes many arguments that have been absolutely standard in feminist-oriented history over the past half century. In her view, the persecution of witches is a perfect symbol of the oppression of women, a means of ensuring absolute patriarchal control, and the suppression of the slightest traces of female initiative or independence. Gage cites, and perhaps originates, the later-popular claim that some nine million women perished in the Early Modern witch hunts (the actual figure is closer to 80,000, over four centuries). Gage’s high figure represents a “holocaust,” and she actually does use the word.

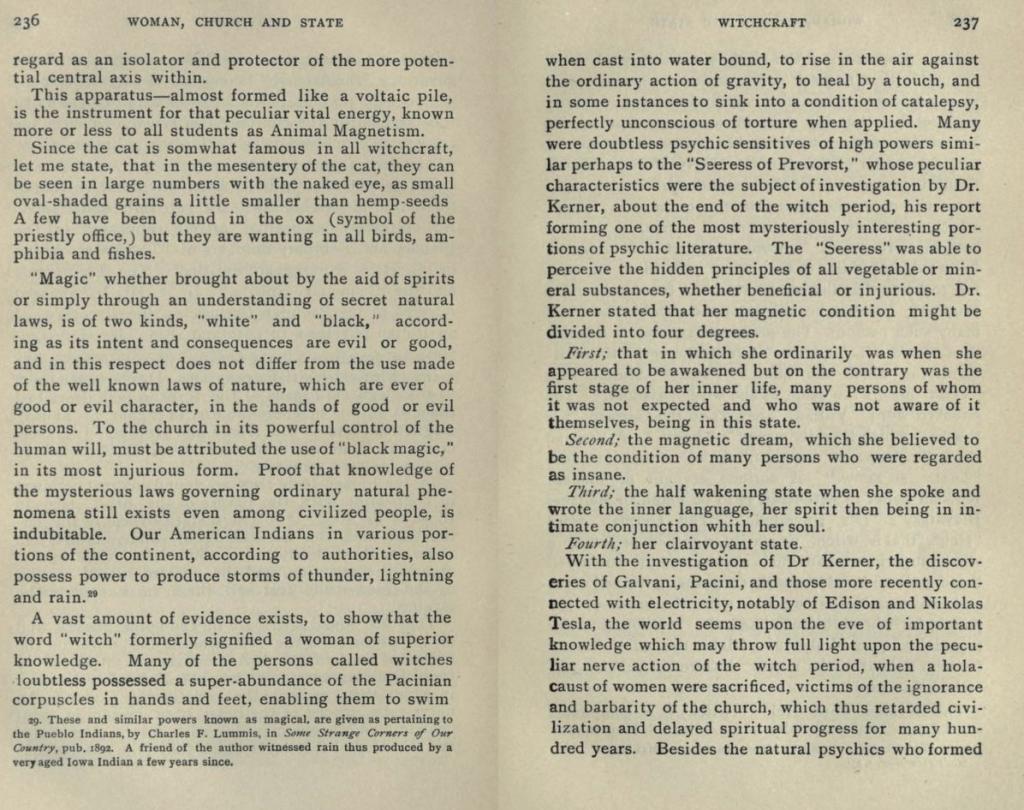

On close examination, she says, women were totally innocent of the harmful crimes of which they are accused, but that does not mean that there was no basis to the male-driven persecutions. If accused women were not actually carrying out curses or malevolent witchcraft, they really did possess scientifically-based psychic powers that we might call forms of ESP. This was a common idea in the literature of the turn of the twentieth century, and often features in horror or supernatural oriented stories. To support the idea, Gage cites the work of the Italian scientist Pacini, who had identified receptors in the nervous system, the “Pacinian corpuscles”, as well as the electrical discoveries of Thomas Edison and Nikolai Tesla. Witches were wise women who had learned to deploy these forces to incredible effect:

A vast amount of evidence exists, to show that the word “witch” formerly signified a woman of superior knowledge. Many of the persons called witches doubtless possessed a super-abundance of the Pacinian corpuscles in hands and feet, enabling them to swim when cast into water bound, to rise in the air against the ordinary action of gravity, to heal by a touch, and in some instances to sink into a condition of catalepsy, perfectly unconscious of torture when applied.

Witches genuinely were healers, and they had command of powers as yet unknown by science. The persecution of witches was in reality a Church campaign against the cutting-edge science of the day. After the 1890s, the next landmark in making anything like such a core feminist argument appeared only in 1973, when Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English published their much-cited Witches, Midwives, And Nurses: A History Of Women Healers. This argued that

Witches lived and were burned long before the development of modern medical technology. The great majority of them were lay healers serving the peasant population, and their suppression marks one of the opening struggles in the history of man’s suppression of women as healers.

To give an idea of strictly current attitudes to such matters, I note the very recent publication of the collection of essays in Soma Chaudhuri and Jane Ward, eds., The Witch Studies Reader (Duke University Press, 2025), which offers “a pathbreaking transnational feminist examination of witches and witchcraft that upends white supremacist, colonial, patriarchal knowledge regimes, this volume brings into being the interdisciplinary field of feminist witch studies.” I mean no criticism of that book when I mention that I would cite Matilda Joslyn Gage as the authentic pioneer of such “feminist witch studies,” and already, even way back then, in a pretty interdisciplinary way. And she was very good indeed on “patriarchal knowledge regimes.” But unless I am missing something, I don’t see her cited even once in the index of that Reader. Weird indeed.

Ideas about religion and spirituality were in a tumult in and around 1893, with far-reaching implications for any conventional understandings of Christianity, past or present.

To be continued.