Last Thursday morning, May 8, 2025, as I finished up a morning Zoom call with a Mexican theologian to discuss the theological implications of my Juan Diego manuscript, I looked at the time and nearly panicked. Had I missed it?

Hastily searching online for a live feed from the Vatican, I ended up with French audio. Moments later, white smoke began billowing from the Sistine Chapel chimney: the evening vote in Rome had resulted in a new Supreme Pontiff for the Catholic Church! Alone at my dining room table, and without even knowing the new Pope’s identity, I began weeping, laughing, and shouting at my laptop.

***

A papal interregnum can an interesting period to be Catholic. Depending on how close one feels to the Holy Father, intense grief can follow a death announcement. So it was for me with Pope St. John Paul II, who was Pontiff most of my life. While home on a break from my doctoral program, JPII’s death watch began. Emotionally spent after days of waiting at my computer, I stepped outside; my dad found me lounging in the grass a few minutes later to tell me the pope had died. I was bereft. I had seen JPII as a schoolgirl in Phoenix, as a teenager at World Youth Day-Denver, as a young adult at World Youth Day-Paris, the Papal Palace in Castel Gandolfo, and St. Peter’s Basilica, and as a graduate student in Mexico City for the canonization of Juan Diego. I felt like I knew him and he knew me, but more than that, that he loved me. I certainly loved him. Only the election of Benedict XVI – the dissertation advisor of the priest who founded the Great Books Program I attended – alleviated my grief.

For this post, I’d like explore papal conclave history and highlight the emotional experience of moving from Sede Vacante – the empty seat (of Peter) to those joyful words, Habemus Papam – We have a Pope.

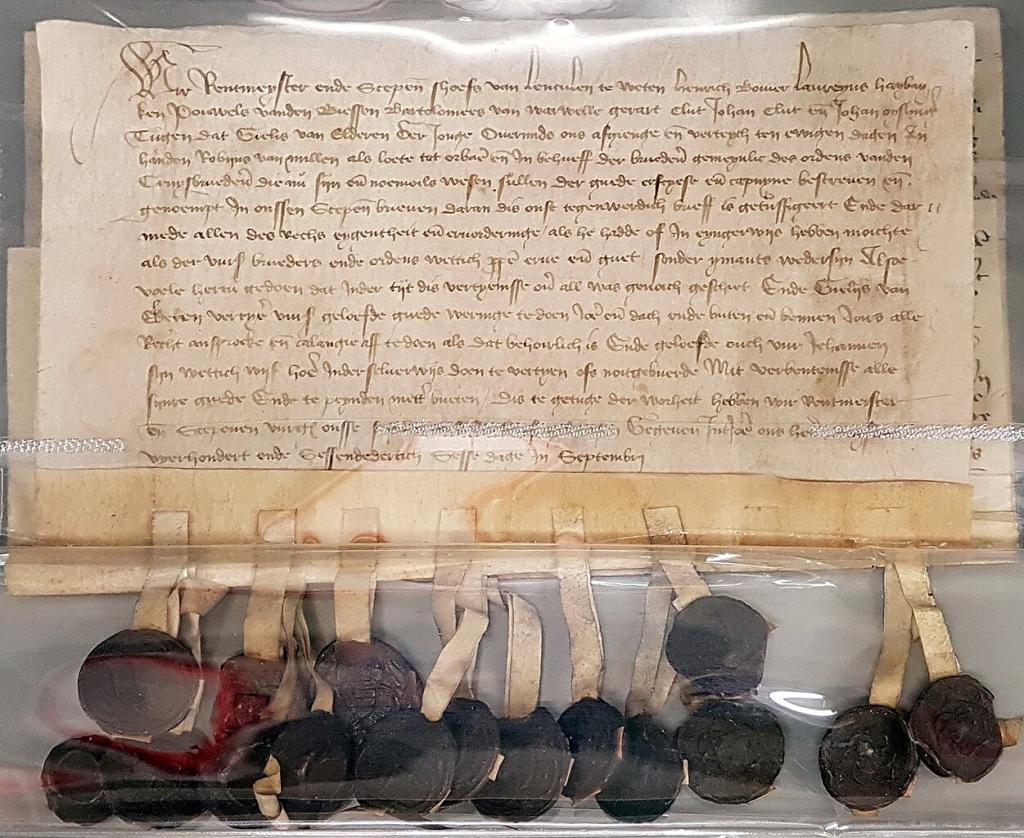

The word conclave, or “lockable room,” derives from the Latin con, “with” + clavis, “key;” in Spanish, it’s even clearer: con, “with” + clave, “key.” The origins of the papal conclave date to the thirteenth century, Viterbo, Italy, where the papal court had moved due to instability in Rome. A two-year stalemate in the papal election there prompted locals – who were covering expenses – to first lock the cardinals in the great hall of the Palazzo dei Papi (Palace of the Popes), then feed them only bread and water, and then remove the roof to expose them to the elements and “let the Holy Spirit in.” The cardinals recorded the experience in a 1270 document, noting that they were locked in an “plazzo discoperto,” or unroofed palace. Oral tradition holds that the cardinals set up tents and camped, a claim substantiated by holes in the hall’s flagstone floor to accommodate tent poles. The cardinals nevertheless delayed another 15 months before electing Gregory X (1271-1276), who promulgated a constitution calling for a closed conclave to elect future popes, a decree that Boniface VIII (1294-1303) incorporated into canon law.

This did not solve all problems (the Avignon period of multiple popes comes to mind), and later popes continued to add additional regulations. In the sixteenth century, Pius IV (1559-65) codified all conclave procedural laws that had been promulgated since Gregory X. A few pontificates later, Gregory XIV (1590-91) forbade placing bets on the papal election, the duration of a papacy, and the selection of new cardinals – under pain of excommunication.

The seventeenth century brought more changes. Even after Gregory XV (1621-23) issued formal legislation detailing conclave procedure, the Catholic kings of Europe began exercising the royal right of exclusion, that is, they tasked their cardinals with appearing before the conclave and declaring certain papal candidates inadmissible. The Church tacitly accepted these kings’ right of veto, leading to cardinals being banned from the papacy in 1721, 1730, 1758, 1830, and 1903. Following the 1903 conclave, newly-elected Pius X (1903-14) abolished the royal right of exclusion under threat of excommunication, going on to codify conclave procedure on December 25, 1904.

Other popes have also introduced modifications, like Pius XII (1939-58), who altered the required majority from two-thirds to two-thirds plus one and Paul VI (1963-78), who limited the voting age of the cardinals to under 80 and capped the number of voting cardinals to 120. Pope John Paul II (1978-2005) decreed that after 30 ballots the two-thirds majority might, at the discretion of the cardinals, be superseded by a simple majority vote, but Benedict XVI (2005-2013) restored the two-thirds majority requirement, which is what we saw with the election of Pope Leo XIV (2025-). Though this was not the first time that the number of voting cardinals exceeding 120 – having occurred at various points during the last three pontificates – the 2025 conclave was the first time a papal election consisted of more than 120 cardinal electors; on April 30, 2025, the College of Cardinals confirmed the right of 133 eligible cardinals to vote.

***

With much of the world, I watched the live feed from the Vatican on May 8, waiting for the announcement of the name of our new Holy Father. Just the night before, as my children and I prayed for the voting cardinals and talked about the conclave, I had told them we would definitely not see a U.S.-born pope, but maybe we’d have a pope from Africa or Asia.

The reason for our lack of a “unitedstatesian” pope is partly practical – for over a hundred years, cardinals from the U.S. simply could not reach Rome in time to participate in the conclave. The Archbishop of New York, John McCloskey, who became the first U.S. cardinal appointed in 1875, set off for Rome in 1878 upon receiving a telegram announcing the death of Pius IX, but travel delays meant that he arrived five days after the conclave began, when Pope Leo XIII had already been elected. [Though as far as I know our first U.S.-born Holy Father taking the name Leo XIV was not meant to link him to the first U.S. cardinal eligible to become pope, the historical connection is nonetheless interesting]. Cardinal McCloskey died during Leo XIII’s 25-year reign, never voting in a papal conclave.

The first U.S. cardinal to vote in a conclave was James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, but only because he was already in Rome when Leo XIII died in 1903. William Cardinal O’Connell of Boston was not so fortunate. In 1922, after journeying by plane, ship, and express train, he ran through the streets of Rome only to be greeted by the bells of St. Peter’s, signaling the election of the new Pope. In a private audience with newly-installed Benedict XV, Cardinal O’Connell requested that the waiting period between a pope’s death and the convening of the papal conclave be increased from 10 to 15 days, with the option to extend it to 20 days. As a result, he voted in the next conclave, which convened in 1939.

When, on May 8, 2025 the the cardinal proto-deacon finally appeared on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica and declared, “Annutio vobis gaudium magnum: habemus papam,” I cheered as loudly as everyone in St. Peter’s Square, straining to hear the Latin name that followed. I heard Humberto and in momentary confusion wondered if we had a Mexican pope, until the EWTN commentators clarified that we had our first U.S.-born pope: Robert Francis Cardinal Prevost.

For a moment I was too stunned to feel anything, but then my tears flowed anew. To have a pope who hails from your own country, who understands Catholicism in the U.S. in a way no other pope has, who is a native speaker of your own native language… My tears of joy matched the tears I saw in the eyes of so many others watching in St. Peter’s Square that day. Then our new Holy Father, Leo XIV, began to speak, his voice reminiscent of my beloved JPII… and then, in Spanish, he greeted the faithful in his former post in Chiclayo, Peru…

With effort, I tore myself away from my laptop and drove to my children’s school for Mass, in which my son’s 3rd-grade class was doing the readings and Prayers of the Faithful. In less than an hour after the announcement of Pope Leo XIV – and with great joy! – my children, the other school families, and I prayed for our new pope by name during the Eucharistic Prayer.

Like the rest of the world, I’m anxious to see how Leo XIV will lead the Church.

POSTSCRIPT: My mother called as I finished this post. She had just watched the clip I sent her of John Paul II’s election on October 16, 1978, when I was 13 months old. I had wondered if she had watched it live, but she reminded me that I had been hospitalized and nearly died around that time, so she had not. Watching it now, she realized she had never told me that my pediatrician, Dr. Felici, was the one to inform her about John Paul II’s election, and that he was especially joyful because it was his uncle, Cardinal Proto-Deacon Pericles Felici, who had announced the election of Karol Wojtyla(!). You can watch that clip here.