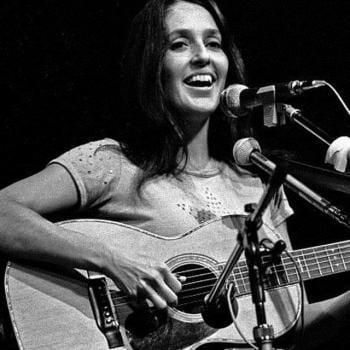

“Above all, she is the girl who ‘feels’ things”—Joan Didion about Joan Baez (Didion, 48)

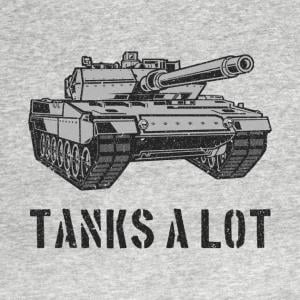

It was one of the first times I arrived on campus, a late August or early September day in Pasadena. I was wearing a shirt that had a picture of a tank followed by the words ” A Lot”. My wife tells me all the time how much she hates these type of adolescent shirts that someone my age should probably stop wearing. She often assures me that a simple plain T would be fine.

You know the type of shirts. I think I bought mine at Kohls or Target (usually found folded and displayed with its twins of various sizes and a sign stating $19.99 each or 3 for $30). I often wear these shirts enough that the tank on the shirt begins to slowly fade away into an almost ghost like trace, so the “A Lot” is now what stands out. These shirts end up being part of my pajamas along with basketball shorts because it is often hot at night, at least for me, in Southern California. My response to my wife’s frustration is that these shirts are comfy—I get all the mileage I can manage out of my shirts.

At some point later in the afternoon, someone came up to me, violently shaking his head in disapproval. He then said that he could not believe I would wear a shirt with a tank on it. I remember being stunned by this sudden, unwanted discussion with a stranger. I softly answered in disbelief: “But…tanks…a lot?” Immediately he left, and I was left stunned by this brief interaction. This felt like such a Southern California moment. He was young.

If the indignant look I received was a result of a bad fashion choice then I could understand, being somewhat sympathetic (it really is a stupid shirt). However, the mere symbol of the tank, joke aside, was enough for my accuser to spur this confrontation.

This story from my past fashion choices reminds me of a chapter called “Where the Kissing Never Stops” from California born writer Joan Didion’s classic book of essays Slouching Towards Bethlehem (Didion, 42-60). In this chapter Didion reveals the workings of American folk singer Joan Baez’s Institute for the Study of Non-Violence in Carmel, California.

I have spent a lot of time with both Joan’s (see my last few Anxious Bench posts and one around Christmas for Baez). I have spent the last couple of years doing historical research on Baez. Believe it or not, I cite Didion quite a lot in a few of my essays and even in my first book about her travels to El Salvador in the 1980s (I don’t think the book is as bad as some make it out to be). As a voracious reader, I really appreciate a good writer, and Joan Didion can certainly turn a phrase with the best of them.

So what does the writer Joan think of the folk singer Joan? On the one hand, it looks like Didion sort of admires Baez, even though she finds her utterly naïve. On the other hand, Didion considers Baez a little more than a symbol, calling her “the Madonna of the disaffected” (Didion, 47). Her capacity for adolescent innocence is what endears Joan Baez to the youth of America, but probably not much for the mature Joan Didion.

I am still researching whether or not Baez ever responded to Didion’s essay. However, the phrase that Baez “feels” things made me think of my tank shirt accuser who had the audacity to basically call out my stupid shirt. It was the fact that I had a war machine on my shirt that made him feel that he just had to say something. Oftentimes what we might label Christian pacifism takes on this tone of silliness. It can be loud, sometimes obnoxious, but it often means well. So I shrugged when the young man left me and my tank shirt because in the big scheme of things this encounter was not a big deal.

Still, for all the performative moves that some commit in the name of peace it is hard to debate the fact that at the center of Christ’s work is peace. Peacemaking in our violent world is tough work. I like to highlight the peacemakers in history class (too much attention already given to the warmakers—and tanks) because where would this world be without them.

In her new book Didion & Babitz (which I am currently working on for a review), writer Lili Anolik states the following about Didion: “Joan’s unblinking voyeurism: her tragic flaw, her saving grace” (Anolik, 301).

There is a part of me that appreciates the distance that Didion takes when writing about her subjects. It’s cool and calculating. This attention to details, especially her way with words, was her saving grace. However, I find the “unblinking voyeurism” hard to reconcile with real pain and suffering that we see in history. This detachment was her tragic flaw.

In fact, the contrast between Didion and Baez could not be clearer. Whereas Didion keeps a cool distance, Baez feels her way into the center of the drama. One of the major points I learned in researching Baez’s life was how some of the most important Christian peacemakers (Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, and Cesar Chavez) all found her not naïve but a committed leader and friend of movements centered in non-violence. That is quite the resume. I am not sure Didion is on such a list.

Still, I think some criticize the writer Joan too much (there are some scathing essays of recent out there on the internet). There is something about her distance and cynicism towards American social-political life that is possibly needed today. Alissa Wilkinson’s new book about Didion perhaps touches upon this point (it is on the to-read-list).

Historians cannot help being voyeurs like Didion—we look where sometimes we are not wanted, we pry, and we gossip. And like Didion, we often step away from the drama, collect ourselves, and write about events that hopefully helps the reader see reality in a clearer way, trying not to get distracted by our own feelings or stupid shirts.