With the recent passing of Pope Francis, there has been a lot of discussion about the pope’s legacy. Described by NPR as “one of the most popular popes in decades” as well as “a controversial figure,” Pope Francis was willing to wade into controversial topics and deliver messages that pushed against political figures and topics. Posts from my Anxious Bench colleagues Philip Jenkins (After Francis: What’s Next in the Vatican, Who Will Be The Next Pope?, and Popes, Prophecies, and the Apocalypse) and Daniel Williams (Why Evangelicals Mourned John Paul II– But Not Francis) took up questions of Francis’s legacy, of the tensions that will shape the choice of the next pope, and of some history around papal election in conversation with prophesy and eschatology. I will not repeat these themes here, nor will I try to offer extensive commentary on Francis’s legacy or Francis himself. However, in reading these recent news stories, a question kept coming to mind: what makes a pope “great”? What should the standard be for assessing a papacy? Thinking about Pope Gregory I (540-604), one of only two popes to be given the epithet “the great,” might help us answer some of these questions. Further, he might provide us with a framework to evaluate what sort of pope we might hope to have on the Holy See when the coming conclave concludes.

Pope Gregory I: Magistrate, Monk, Missions Advocate

Gregory was born in 540, the child of a wealthy Roman senator and from a patrician family already well connected in political and ecclesiastical affairs. The very fact that we know, with some certainly, Gregory’s birth year tells us quite a bit about the privilege that he was born into. He received an extensive education– the best available in Rome at the time, it seems from his biographers’ accounts– and had a quick ascent into political power. Gregory was named the prefect of the city of Rome (praefectus urbi)- the chief magisterial office in the city, in his 30s (Kevin Madigan, Medieval Christianity: A New History, 57).

Gregory held this office during an acutely difficult year. As noted in George E. Demacopoulos’ Gregory the Great: Ascetic, Pastor, and First Man of Rome, during Gregory’s term, a series of catastrophes upending civic and ecclesiastical order occurred: the Lombards threatened the city, isolating it from the Roman emperors in Ravenna and Constantinople; the pope died, with almost a year until his successor was elected; finally, the general responsible for defending the city died. Gregory was left carrying much of the weight of the care of the church and the city, almost entirely on his own (Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great, pp. 2-3).

Yet it does not seem that Gregory left public life because he found it too difficult, but because he had always desired to live as an ascetic, committed to theology and reflection rather than to active work. The thoroughness of his transition into the monastic life shows this commitment: after the death of his father, Gregory transformed all of his family’s wealth into seven monasteries. He entered one as a novice and took up ascetic practices with great vigor, following an unusually rigorous regime of fasting, prayer, and reflection (Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great, p. 3).

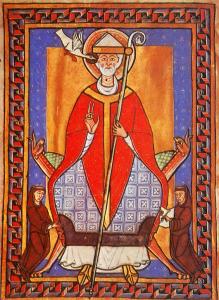

Accession number

Ms.315, tome II, f.1 verso. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

But Gregory’s unique skills–as pastoral leader, as former bureaucrat and administrator, and as one of a shrinking number of men with both extensive education and administrative experience in Rome–meant he was not to remain in the monastery for long. Against his desires, he was first chosen in 579 to act as papal representative to the emperor on Constantinople and then elected into the papacy in 590 (George Demacopoulos (trans.), The Book of Pastoral Rule, p. 10). In the face of plague, invasion, famine, and flames, and flooding, the Rome in which Gregory lived and served was one in great need. As Gregory described it, “for those still living only sorrow and tears . . . Rome is deserted and in flames.” (Letter as quoted in Madigan, Medieval Christianity, p. 58). Gregory did not inherit a papacy that was stable, nor a church that was thriving, but instead a church in crisis, filled with terrified and suffering individuals.

Perhaps because this was the context of his political and papal ministry, Gregory’s surviving works– over 800 letters, Morals in the Book of Job (on suffering and hope in Job), and the Book of Pastoral Rule– emphasize hope in suffering, faith in apocalyptic times, and the care of souls according to their needs and contexts. His most famous writing, the Book of Pastoral Rule, proved formative for pastoral care in the West for centuries to come. It contains sections on the selection of clergy, the purity of life to which a pastor should aspire, the different kinds of people who one will encounter as pastor and how to care for each, and warnings against personal ambition in pastors. Alongside these writings, Gregory left a legacy of reform, whether of clergy, the mass or the liturgy (Gregorian chant bears his name, and many of the prayers used in the mass come from his works). He also left a legacy of mission work and evangelism, sponsoring and overseeing mission work in various parts of Europe and Africa. Serving as pope in a time of cultural change, political crisis, and dire human need, Gregory’s legacy centers on the care of individuals using his two great skill sets: political administration and pastoral teaching.

Gregory’s Two Careers: Politics and Pastoral Care

While looking back, Gregory’s time as prefect and as pope seem complimentary, Gregory himself articulated feeling torn between two roles, that of service and that of contemplation. As George Demacopoulos summarizes, “if there is any single axiom that explains Gregory as both theologian and papal actor, it is that he felt ever conflicted between his inclination for ascetic ideals (namely humility and retreat) and a Ciceronian-like compulsion to public service” (Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great, p. 4). Similarly, Gregory was a man living and serving at a time when tensions in society pulled in opposing directions. Gregory was both Roman and medieval. He saw himself a loyal Roman citizen of the empire and a citizen of heaven– but while Gregory seems to have felt the tension between a life of service and a life of contemplation, this tension between politics and pastoral work seems to have been less acute for him.

In some ways, Gregory was a man of his culture and of his time. As Richard Allington points out, the current scholarly consensus is that Gregory “worked within” rather than tried “to break away from his contemporary social framework” (p. 7)– and yet his concerns do not map directly onto the social or political concerns of his day, but show a sort of pastoral care through political engagement. Gregory might have been a man of his time, but he was not typical in the ways in which he saw his faith and his political commitments interacting. Gregory’s commitment to asceticism and his ascetic theology formed the foundation for his other theological positions, including on pastoral care and towards suffering and papal power (Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great, p. 8).

The activities that Gregory undertook indicate a theological commitment to Christ above all, revealed through an emphasis on the least of these, the marginalized individuals that Christ focused on his own ministry. Gregory used papal money to ransom prisoners of war, to care for persecuted Jews, and to care for those within Rome. His care for refugees brought thousands of individuals fleeing from the wars in the north to Rome, and Gregory took on the responsibility for caring for them. To feed the thousands of refugees entering the city in a time of famine and flooding, Gregory imitated his actions when he had entered into the ascetic life, donating the resources of his family to the church. In this instance, having already given away all of his family’s money, Gregory used the income of the papacy for refugee aid and for defense of the city of Rome and the vulnerable populations therein (Madigan, Medieval Christianity, 59). His theological commitments to serving God, not money, tangibly played out in his policies towards refugees, towards missions work, and towards other vulnerable groups that he saw as under his care.

As a pope in a time of transition, Gregory also provides an example of theological thought and action in a changing world. As Allington notes in an article on Gregory’s models of pastoral care, “his application [of pastoral care as laid out in the Book of Pastoral Rule] demonstrates the ways in which he saw Late Antique society changing and how he respected ancient Christian and local traditions, while harnessing these changes to promote his understanding of Christian orthodoxy.” (Allington, “Honey and Venom,” p. 5)

The Great? The Measure of a Pope

So, how to assess the legacy of a pope? What makes a pope great? I think Gregory’s reign is particularly revealing; while considered one of the doctors of the church, Gregory gains this title through pastoral care and service to the least of these, not theological debates. As Madigan states, it was during his time as a monk that Gregory took up another title, “‘servant of the servants of God’ (servus servorum Dei), one that he later applied to himself as pope, as all his successors on the throne of St. Peter have down to this day” (p. 57). It seems that a key part of considering the legacy of a pope needs to be considering the degree to which any given pope used the power of the papacy to serve those without power, without personal ambition or regard for one’s legacy.

It’s worth noting here that just because power did not seem to be Gregory’s primary aim does not mean he did not gain considerable amounts of it. As Madigan noted, Gregory’s approach to the papacy and some of his work was “to reverberate for centuries. The bishop of Rome had become, in a power vacuum, the secular leader of the city and the territory surrounding it. He had used the considerable resources of the Roman church to feed the refugees and defend the city of Rome. This secular rule was to be a mark of the medieval papacy.” (Madigan, Medieval Christianity, p. 59; similar comment on Allington, “Honey and Vinegar,” p. 5) It’s also worth noting, as we turn back to modernity, that assessing a medieval pope is quite different from assessing a modern one. Gregory has had the luxury of editorial intervention to cultivate a rather controversy-free image (Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great, p. 5). But given the widespread approval of Gregory’s work from his contemporaries, as well as some of the tangible proofs of his policies, it seems fair to say that Gregory’s title for himself as the servant of the servants of God was not just aspirational, but acted out in where he placed his time and resources.

Many assessments of Francis’s papacy emphasize theological positions or tensions. But that is not the framework by which we have assessed Gregory. Instead, Gregory is remembered as a great pope primarily because of his actions: his care for refugees, his attention towards peoples on the edges of his world, his commitment of his wealth and privilege for the cause of the church. Under this rubric, Francis’s daily attention to Catholic believers in Gaza, to migrants and refugees, and to those marginalized on account of gender or sexuality, seems to follow the model of Gregory’s pastoral rule. James Horowitz, a New York Times reporter who covered Francis throughout the entirety of his papacy, wrote that “Francis cared about the plight of migrants, the displaced victims of war and the most forgotten and marginalized among us, no matter their religion . . . For him, their suffering was real.”

I’m confident that Francis and Gregory might have disagreed on many things and might have been surprised at what each saw as theological orthodoxy or orthopraxy. But I think they might still have considered each other to have fulfilled the office of the papacy well– and would both hope for a new pope who follows in this example, of using the papacy to speak into both political and theological affairs on behalf of the powerless, whom Christ loves.