My recent blogs have focused on the year 1893, which I believe marked multiple critical landmarks in American history – social, cultural, and above all religious. Some of those events are famous and well studied, such as the World Parliament of Religions held that year in Chicago, but other developments are not well known, even to specialists. Today I will talk about a very important study of Native American spirituality that appeared in that year, one that almost surreptitiously offered an incendiary commentary on the Bible, and on both Jewish and Christian faiths. And this astonishing work was printed by an agency of the US government.

All Images in this post are public domain. This image is from the Library of Congress.

The New Anthropology

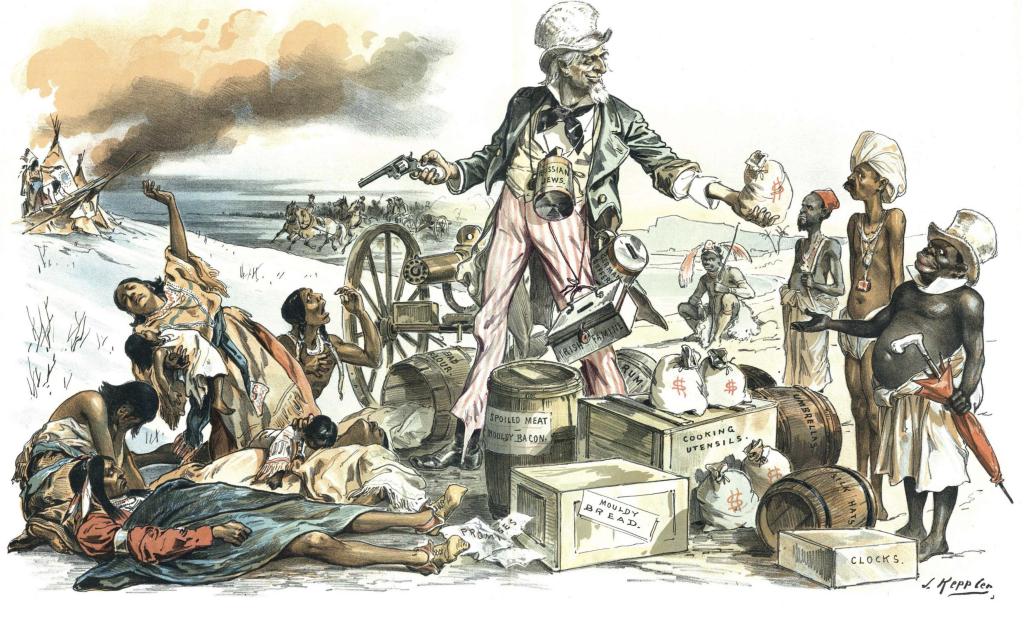

By way of background, the science of anthropology was booming in these years, and scholars devoted great attention to Native American societies, which, they believed, had many parallels to ancient and “primitive” societies. Anthropologists like Sir Edward Tylor ranked such communities according to where they stood on a supposed ladder of ascent, from the savage to the barbaric, and on to the civilized. These findings had many implications for understanding modern and civilized family arrangements, and for religious assumptions. The first volume of Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough appeared in 1890: see the discussion of larger trends in Timothy Larsen’s The Slain God: Anthropologists and the Christian Faith (Oxford University Press, 2014).

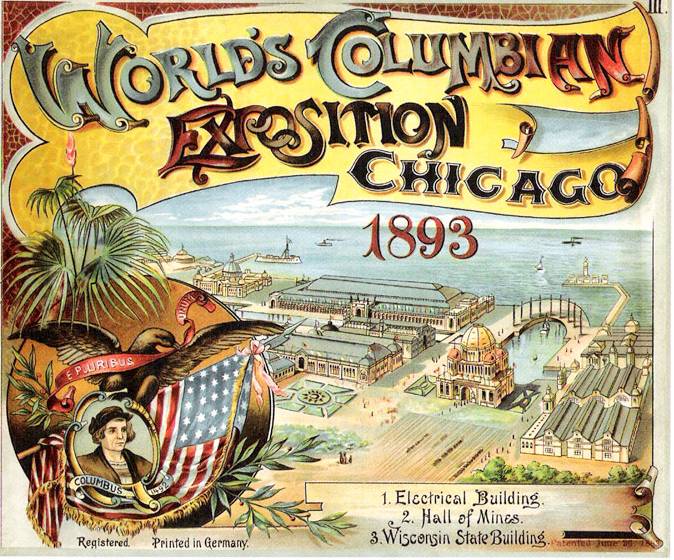

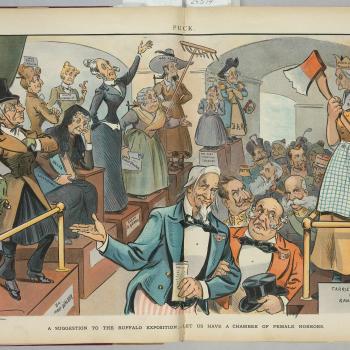

Several developments made the year 1893 crucially important in this story. Successive world’s fairs and expositions played a major role in popularizing anthropological findings to the general audience, displaying Native American dwellings, crafts, and rituals, and even featuring whole “human zoos” of “primitive” peoples. The Centennial Exhibition held at Philadelphia in 1876 had offered many Native exhibits, and the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, sought to show the state of societies as they existed before European settlement. These included performances by Native peoples themselves. Very important for later developments, this research brought the German scholar Franz Boas to the United States, where he became a visible and quite dominant figure for decades to come.

In these same years, non-specialist White Americans were also becoming aware of the range and diversity of Native cultures on their own soil. Given the centrality of the Great Plains in Western mythologies, we inevitably think primarily of figures such as Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and the Ghost Dance movement, which Whites portrayed in terms of savage violence and fanaticism. But at the same time, explanations in the Southwest were producing impressive evidence of more substantial cultures with their temples and even cities, often associated with the Pueblo peoples. In the 1880s, the awe-inspiring cliff settlement of Mesa Verde won growing attention, and that lost world penetrated the popular media, as well as fiction. In 1890, Adolph Bandelier published his brilliant reconstruction of ancient Pueblo life in his still insufficiently known novel The Delight-Makers.

In 1893, Henry Blake Fuller published a novel set in contemporary Chicago which represented an innovative breakthrough in urban, naturalist, and social realist fiction, and which set the stage for Theodore Dreiser. But despite its very contemporary setting, the setting in the skyscrapers and multi-storied apartments led Fuller to give his book a title that would seize the interest of a public used to hearing about such mysterious Native cities as Mesa Verde: the book is called The Cliff-Dwellers. (Fuller later earned fame as a pioneer of gay themes in American fiction).

I’ll be returning to that Pueblo idea, and the fact that it was so well established in American thought.

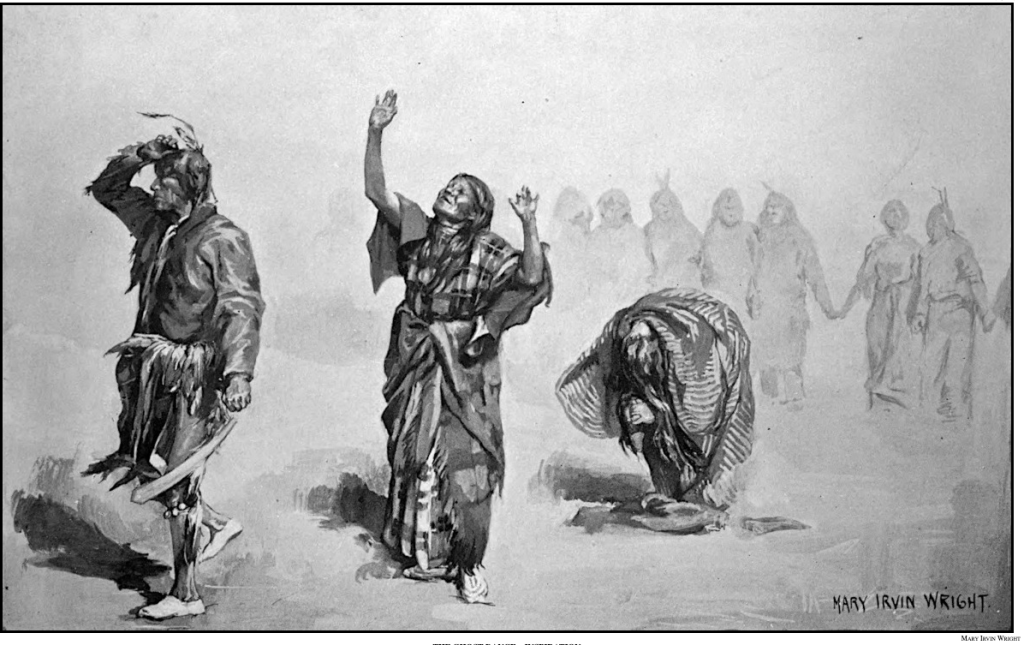

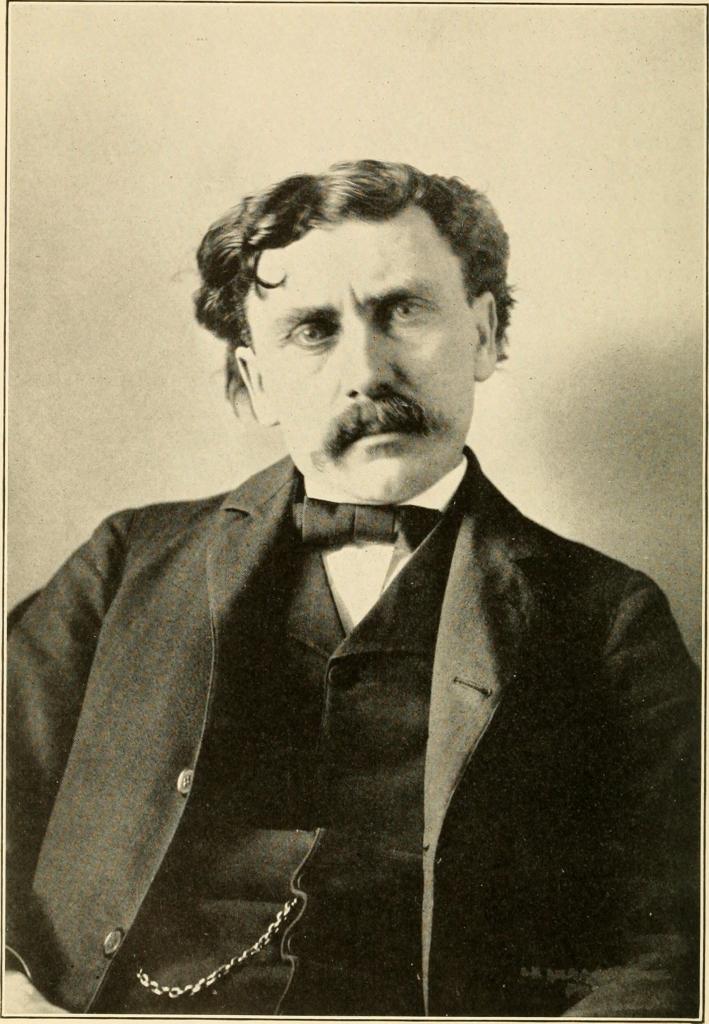

The Indian Man

A key figure in the American story was ethnographer James Mooney, “the Indian Man,” who lived for many years with Native peoples. One of his greatest achievements was his very sizable report on The Ghost-Dance Religion And The Sioux Outbreak Of 1890, which studied the messianic and millenarian movement led by the prophet Wovoka. The messianic expectations that now surged led to a conflict with US forces, who feared that fanatical devotees were preparing acts of violence. The affair culminated in the notorious Wounded Knee massacre of 1890. For White Americans, the whole affair epitomized the irrational savagery that they attributed to Native peoples.

Mooney’s analysis of the affair appeared in 1896, but it reflected years of research and observation, and much of it was actually written in 1892-3. This masterful work survives as a classic study of a millenarian movement – and a movement that incidentally drew heavily on Christian and evangelical influences. But many of Mooney’s remarks are subversive, and must be read carefully to appreciate their importance and, in the context of the age, their radicalism. Fittingly for an age when Americans discovering other global faiths, Mooney’s book contextualizes Indian “Primitivism” alongside any and all world religions. “The doctrines of the Hindu avatar, the Hebrew Messiah, the Christian millennium, and the Hesûnanin of the Indian Ghost Dance are essentially the same, and have their origin in a hope and longing common to all humanity.”

One of Mooney’s chapters, on “Parallels in Other Systems,” demands special attention for its clear relativism, and its refusal to grant any unique status to Biblical religion (and as I say, in a report published by the US government). As Mooney argues,

The Indian messiah religion is the inspiration of a dream. Its ritual is the dance, the ecstasy, and the trance. Its priests are hypnotics and cataleptics. All these have formed a part of every great religious development of which we have knowledge from the beginning of history.

He then expands on the unavoidable Biblical parallels to every one of these components:

In the ancestors of the Hebrews, as described in the Old Testament, we have a pastoral people, living in tents, acquainted with metal working, but without letters, agriculture, or permanent habitations. They had reached about the plane of our own Navaho, but were below that of the Pueblo. Their mythologic and religious system was closely parallel.

Their chiefs were priests who assumed to govern by inspiration from God, communicated through frequent dreams and waking visions. Each of the patriarchs is the familiar confidant of God and his angels, going up to heaven in dreams and receiving direct instructions in waking visits, and regulating his family and his tribe, and ordering their religious ritual, in accord with these instructions. Jacob, alone in the desert, sleeps and dreams, and sees a ladder reaching to heaven, with angels going up and down upon it, and God himself, who tells him of the future greatness of the Jewish nation. So Wovoka, asleep on the mountain, goes up to the Indian heaven and is told by the Indian god of the coming restoration of his race. Abraham is “tempted” by God and commanded to sacrifice his son, and proceeds to carry out the supernatural injunction. So Black Coyote dreams and is commanded to sacrifice himself for the sake of his children.

Indian Messiahs and Biblical Messiahs

Mooney offers numerous Biblical parallels, including the visions reported by Ezekiel and St Paul. Moreover,

The four gospels are full of inspirational dreams and trances, such as the vision of Cornelius, and that of Peter, when he went up alone upon the housetop to pray and “fell into a trance and saw heaven opened,” and again when “a vision appeared to Paul in the night,” of a man who begged him to come over into Macedonia, so that “immediately we endeavored to go into Macedonia, assuredly gathering that the Lord had called us.” …

And yes, this list of visionary and dream encounters certainly extended to Christ himself:

Fasting and solitary contemplation in lonely places were as powerful auxiliaries to the trance condition in Bible days as now among the tribes of the Plains. When Daniel had his great vision by the river Hiddekel, he tells us that he had been mourning for three full weeks, during which time he “ate no pleasant bread, neither came flesh nor wine in my mouth, neither did I anoint myself at all.” When the vision comes, all the strength and breath leave his body and he falls down, and “then was I in a deep sleep on my face, and my face toward the ground.” Six hundred years later, Christ is “led by the spirit into the wilderness, being forty days tempted by the devil, and in those days he did eat nothing.” Another instance occurs at his baptism, when, as he was coming out of the water, he saw the heavens opened and the spirit like a dove, and heard a voice, and immediately was driven by the spirit into the wilderness. In the transfiguration on the mountain, when “his face did shine as the sun,” and in the agony of Gethsemane, with its mental anguish and bloody sweat, we see the same phenomena that appear in the lives of religious enthusiasts from Mohammed and Joan of Arc down to George Fox and the prophets of the Ghost dance.

And while the Biblical parallels strike us forcefully, Mooney devotes even more attention to the origins of Islam, and the carer of Muhammad. Religions are religions, prophets are prophets, and messiahs are messiahs.

Incidentally, Mooney’s comments about the universal human characteristics that drive religious responses appeared several years before William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience (1902).

About The Plane Of Our Own Navaho

Mooney’s observations are in no sense presented as a diatribe against Biblical faith. Rather, they just note that the Hebrew societies that produced the Bible were as “primitive” as any modern Native Americans, or Africans, or any other members of tribal communities. In his major study of the Cherokees, for example, he remarks quite casually that

Among all primitive nations, including the ancient Hebrews, we find an elaborate code of rules in regard to the conduct and treatment of women on arriving at the age of puberty, during pregnancy and the menstrual periods, and at childbirth.

Imagine reading Mooney’s words in the Christian context of the 1890s, when Higher Criticism was achieving wide influence in elite circles, but was still very controversial indeed. Look especially at one short passage in his Ghost Dance study about the Biblical Hebrews, one that clamors for quotation: “They had reached about the plane of our own Navaho, but were below that of the Pueblo. Their mythologic and religious system was closely parallel.” Read that through the eyes of a White American of the time with all the standard prejudices concerning Native savagery: the novels of Tony Hillerman were still a long way off. And this Mooney man is asking us to see the cherished world of the Patriarchs as equivalent to that! When you have read that line about “the plane of our own Navaho,” how can you prevent yourself reading anything in the Old Testament through that vision, of a society that still has not yet clawed its way up to the level of the Pueblo?

Tylor had popularized the idea of “culture,”, which he famously defined thus:

Culture or Civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.

Christians were taught that the Old Testament offered teachings of absolute and eternal validity. But might they not be the products of a culture, which was roughly akin to that of the modern Navajo? How could they have any relevance for modern eras, still less any force?

The reader might then turn back to Mooney’s introductory sentence, as quoted earlier: “The Indian messiah religion is the inspiration of a dream. Its ritual is the dance, the ecstasy, and the trance. Its priests are hypnotics and cataleptics.” Might an objective observer make the same remark about the Jewish/Christian messiah religion? As I mentioned in a recent column, daring American thinkers of the 1890s were already speaking of “the Christ-myth.”

Applied to the religious context, cultural relativism could be a weapon of mass destruction.