If you follow data and polling around religion and American politics, you’ve probably (whether knowingly or unknowingly) utilized the work of the Public Religion Research Institute. PRRI, an organization founded by Robbie P. Jones and directed by CEO Melissa Deckman, aims “to help journalists, scholars, thought leaders, clergy, and the general public better understand debates on public policy issues and the important cultural and religious dynamics shaping American society and politics.” In addition to creating space for academics and analysts of American religion through fellowships and webinars, the PRRI regularly conducts rigorous polling. Their surveys, available in the Data Vault, are a truly remarkable resource for those interested in American religion and public life, containing a wealth of searchable information about trends going back years.

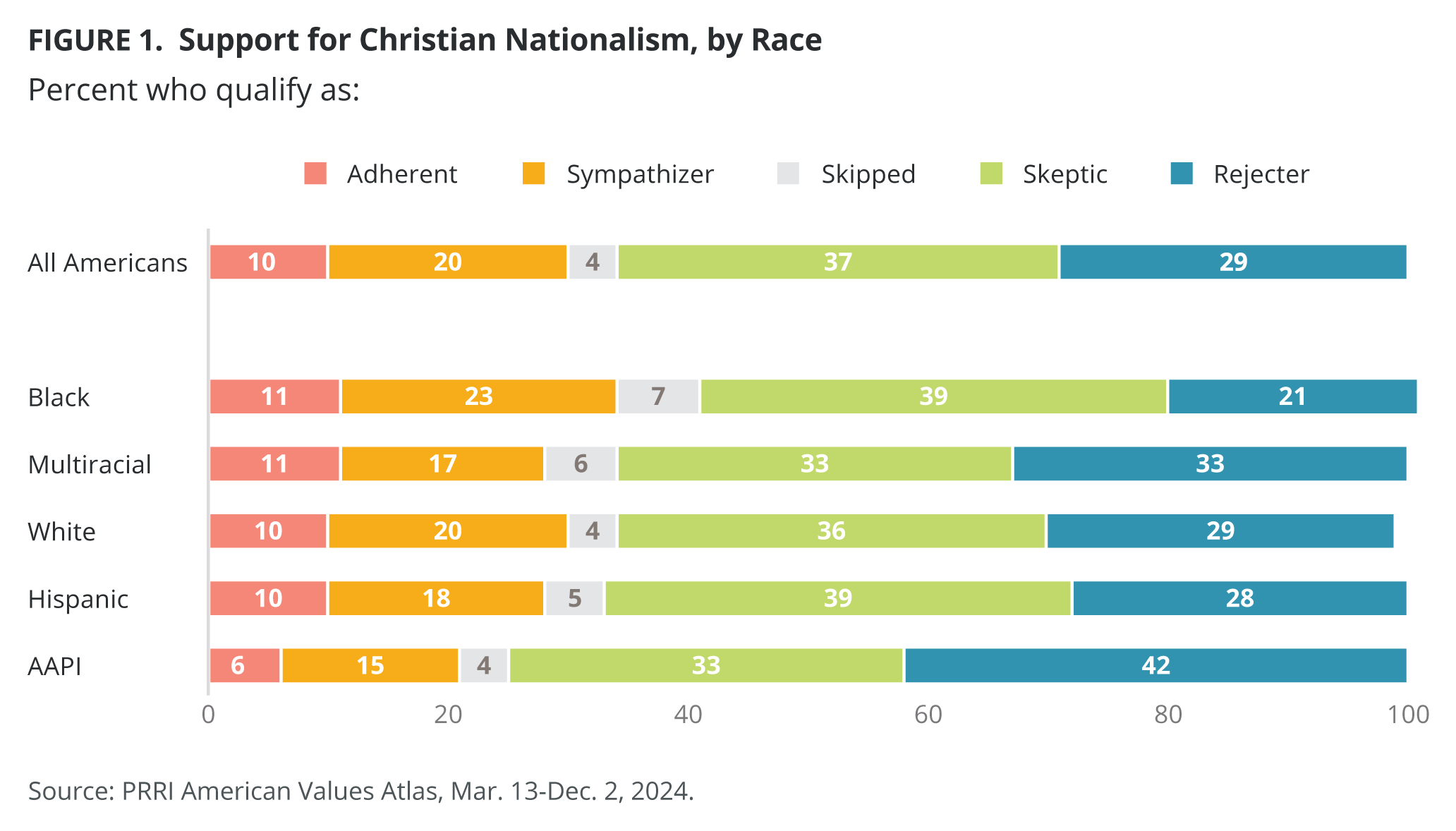

Recently, I used one survey, the 2024 PRRI American Values Atlas, to inform a piece about Black Christian nationalism. For all the talk of white Christian nationalism, actually Black Americans are more likely to hold Christian nationalist beliefs, at 34%, than other groups of Americans (including 30% of white Americans, 28% of both multiracial and Hispanic Americans, and 21% of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders). While somewhat surprising, this finding is rooted in both theological convictions and historical realities, even as it raises new questions about religion and race in the 21st century.

As the piece points out, part of the reason for the high Christian nationalism returns might be that Black Americans tend to be more religious. 59% of Black Americans identify as Black Protestants and 5% as Catholics of color. They have the lowest percentage of folks who identify as religious unaffiliated at 23%. 53% report that they pray personally more than once a week (compared with 41% of all Americans) and only 11% never pray (compared with 22% of all Americans). Almost 40% of Black Americans read the Bible (or another sacred text) weekly or more than once a week compared with 24% of all Americans. Black Americans are also more likely (39%) than all other racial groups and all Americans (27%) to attend religious services weekly with 15% of Black Americans attending religious services more than once a week. Indeed, the Black Church has long provided both theological and organizational power for Black communities in North America, offering autonomous spaces for both solace and resistance.

That could be skewing the findings since Christian nationalist views are more prevalent among Americans who attend religious services frequently. Specifically, over half of those who attend religious services weekly or more qualify as Christian Nationalism Adherents or Sympathizers (51%), compared with 39% of those who attend at least a few times a year and 18% of those who seldom or never attend services. Indeed, When broken down within religious affiliations, the percentage of these Black Protestants who identify as either Christian nationalism adherents (17%) or sympathizers (27%) is lower than that of their white or Hispanic counterparts.

Another potential confounding factor is that Black Americans live disproportionately in the South (56%)— the region that scores highest on the Christian nationalism measures. But still, the results raise provocative questions about religious belief and support for Christian nationalism amongst Black Americans.

When asked if they think U.S. laws should be based on Christian values, Black Americans and white Americans returned the same results, with 14% completely agreeing and 28% mostly agreeing. But when asked if being Christian was an important part of being American, a higher percentage of Black Americans completely agreed (14%) or mostly agreed (22%). Black Americans were in line with white, hispanic, AAPI, and multiracial Americans in responses to the prompt “If the U.S. moves away from our Christian foundations, we won’t have a country anymore,” and polled slightly higher in favor of the statement “The U.S. government should declare American a Christian nation.” When asked if “God has called Christians to exercise dominion of all areas of American society,” 30% of Black Americans completely agreed or agreed. Bafflingly, 6% Black Americans completely agreed with the statement “America was chosen as a new promised land for European Christians,” a higher rate than any other group, albeit still very low.

Perhaps most perplexing, Black Americans seem to be sympathetic to some aspects of the Q-Anon conspiracy. 10% of Black Americans completely agreed and 21% mostly agreed with the statement “There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders,” more than white Americans and similar to multiracial and Hispanic Americans. Same is true for the notion that “the government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation.” On the whole Black Americans are the racial group that score highest as Q-Anon believers (24%) compared with 19% of all Americans. Even controlling for religiosity, 21% of Black Christians qualify as Qanon believers using the PRRI scale vs. 20% of white Christians—at least the same proportion.

So what is going on with these results? I honestly don’t know. They’re varied and, in the full report, often contradictory. While I want to make clear the data do not support any definitive answers to these questions, here are a few hypotheses that may warrant further inquiry.

- The idea of a Christian nation carries very different historical connotations for Black Americans.

In his classic text Exodus!, Eddie Glaude argues that Black national consciousness, as it emerged in the 19th century, was deeply intertwined with Black Christian identity. “Religious underpinnings” meant that, as Glaude writes, African Americans’ uses of nation language stand as a peculiar expression of their ambivalent relation to American.” Black Americans has a religiously animated sense of peoplehood, but understood themselves correctly as a nation in a nation. These intellectual and political traditions rightly complicate meanings of Christian nationalism. In response to the statement “Because things have gotten so off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country,” 6% of Black Americans completely agreed, the highest proportion of any racial group. But, recalling the different historical traditions, some might have in mind not the January 6 rioters, but the Watts uprising, responses to violent police officers, or even Nat Turner, who described his violent rebellion in Virginia in which he and his compatriots murdered slaveholders as one of religious righteousness. “As the blood of Christ had been shed on this earth,” Turner explained, “it was plain to me that the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgment was at hand.”

Black nationalist traditions, sometimes historically anchored in Christianity, may lead to higher returns on the Christian nationalism scale, but with very different meanings attached. (Tobin Miller Shearer recently explored this in regard to Black Power movements of the 1960s.) Scholar and minister Esau McCauley, for example, reads abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ critique of American’s slaveholding Christianity as an argument essentially for a Christian nationalism. “A Christian nation,” was not, according to Douglass, “a status to be claimed but a reality to strive for.” Decades later, Martin Luther King, Jr. would echo these ideas, calling America to be more Christian in its love ethic, not less. In his sermon “Letter to the American Christians,” delivered first at Dexter Avenue in 1956, King imagines the Apostle Paul writing to the Church in the United States. “As I look at you from afar,” King’s Paul writes, “I wonder whether your moral and spiritual progress has been commensurate with your scientific progress.” He urges Americans to “keep your moral advances abreast with your scientific advances” and “live as Christians in the midst of an unChristian world.” But King did not mean that Christians should assert and wield financial, political power.We know that because his Paul explains what he means by a more Christian nation: one that avoids the “tragic exploitation” of misused Capitalism, “division and disunity,” and racial segregation. For Black Christians, the idea of a Christian nation might be conjuring something distinct from other Americans.

- Certain words carry different meanings and are imbued with particular historical and theological contexts. We considered this with ideas of nation above, but it might be true for other words in the survey.

The notion of a “promised land,” for example might mean a mythical past Plymouth, but for Black Americans it might conjure more an imagined just future, the Canaan Land described by Albert Raboteau or King in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” address.

That said, I was surprised that Black Americans surveyed oppose “discrimination” protections for LGBTQ folks, given the historical connotations of that word. I would have expected use of “discrimination” to raise civil rights alarms. Perhaps the double negative in the question threw people off.

It could be that many Black folks, religious or nonreligious, have simply adopted CN ideas for whatever reason. A small minority of Black Americans are Trump supporters and may be adhering to these ideologies out of political affiliation or cultural rebellion.

- But it could represent a theological shift, especially amongst younger Black Christians.

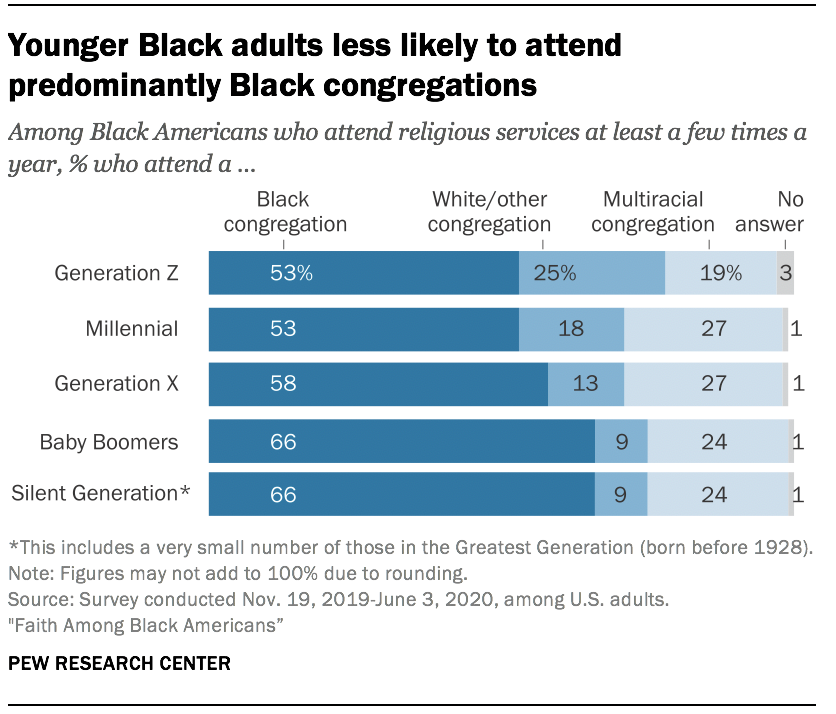

While more research is needed to fully understand these trends, one explanation could be that growing numbers of Black Christians–especially younger ones—have left historically Black denominations and now attend predominantly white or multiracial congregations, many of them nondenominational or charismatic. A 2021 Pew survey indicated that 25% of Black Gen Z-ers who attend religious services at least a few times a year go to White/other churches, while 19% go to multiracial churches.

Amongst those polled in the PRRI Atlas survey, the Black, multiracial and Hispanic populations were notably younger than their White and AAPI counterparts. That could be a factor, too? Perhaps the historical power and influence of the Black Church is waning amongst younger folks, some of whom are finding religious homes in different denominations?

Again, these findings raise more questions than offer answers. But, I’m curious: what do y’all think? Does this represent a denominational shift? New theological currents? Demographic trends? Or are the numbers of Black Christian nationalists still so small that they can simply be accounted for by the higher religiosity?