“All hail to the Printing Press and all its beautiful adjuncts, and all hail to the coming Grapho-Tele-Phone and Photo-Telegraph, the Speech-Recorder and Transmitter, and the Picture-Producer! We hope that Zion City will yet produce that glorious combination.”

J. Alexander Dowie, Leaves of Healing, August 31, 1901.

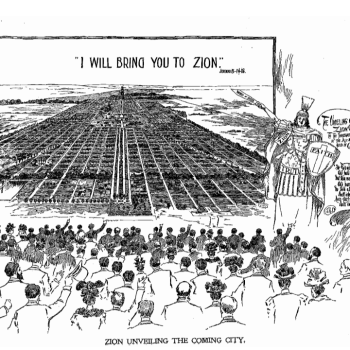

Sitting in his office forty miles north of Chicago, John Alexander Dowie envisioned a bright future for his growing urban experiment: Zion City. His soaring rhetoric, however, betrayed the realities on the ground. While an ambitious city plan was in place, Zion remained little more than an assemblage of muddy roads, wooden sidewalks, and kerosene lamps. The city reached its zenith just three years later, topping out at seven thousand residents. By 1901, the town could boast an electric-powered lace factor and several other small industries. A telephone line was installed by 1903, but Zion never did get its own “grapho-tele-phone.”

Dowie’s Zion City is one of the more well-known examples of Christian utopic experiments in American history, with critical academic treatments starting as early as 1906. Recently, I’ve been working my way through Joel Cabrita’s transnational exploration of Dowie’s life and legacy in her 2018 book, The People’s Zion (apologies for being so late to the party). Throughout my reading, I have been struck by the way technology appears again and again as part of Dowie’s grandiose vision of himself and his work. Technologies, real and imagined, were integral to how he believed God was working in the world, and Zion’s story suggests—to me, at least—that religion and technological change are more deeply entangled than many of us often consider. This entanglement seems all the more important to reflect on considering the influence of techno-billionaire elites and the advent of artificial intelligence.

So… because Cabrita’s book is so good, and Dowie is so interesting, and someone gave me access to a blog, I’m going to spend the next three posts exploring Dowie and his techno-utopic vision for Zion City, Illinois. In much of this, I’ll be reliant on Cabrita’s and others’ great work, but I hope there will be more interesting takes along the way.

From Social Reform to Faith Healing

Dowie’s early life reflected the technological, migratory, and social changes wrought by the First and Second Industrial Revolutions. Born in Edinburgh in 1847, he moved with his family to Adelaide, Australia in 1860. Like so many from the United Kingdom, the Dowies ventured into the industrializing hinterlands of empire to find new opportunities, and like many other middle-class evangelicals, what they found was urban poverty and all its accompanying vices: drunkenness, licentiousness, and spiritual decline.

In 1872, J. Alexander began fighting to end such social ills by advocating for national temperance as a congregationalist minister in Alma, Australia. His naturally combative temperament, however, meant he rarely kept a post long. By 1882, he had left the Congregationalists and landed a new post in Melbourne’s impoverished Collingswood neighborhood.

In the thick of the urban jungle, Dowie joined forces with the Salvation Army whose “appropriation of working-class culture and idioms” represented a new, more radical approach to addressing the social ills of urban poverty through an individualist call to lives of holiness. The partnership was not to last, however. True to form, Dowie’s authoritarian tendencies led to a church split, a property dispute, an unauthorized street procession, and multiple trips to jail. Dowie continued to make news, vying publicly with spiritualists, the “bacchanalian legion in Parliament,” and, oddly, the temperance league. During these battles, he began to embrace the growing divine healing movement, officially adding medical doctors to his list of adversaries.

Cut free of any other associations, Dowie formed his own church in Melbourne in 1883. Five years later, he founded the “International Divine Healing Association” and was bound for San Francisco. There, his association received requests for prayer by mail and telegram, however, prayers for healing were only forthcoming for those who had paid their tithes on time. Within two years, Dowie had become notorious in the city for his controversial healing practices… and his occasional ventures into securities fraud. He decided to relocate to Chicago in 1890.

From the White City to Zion City

It was in Chicago that Dowie found the stage that he had been looking for. Two days after the opening of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition, Dowie opened the Zion Tabernacle directly across the street from Midway Plaisance. The tabernacle’s large bright façade was meant to stand in testament against the “shameful scenes of wasteful extravagance, unbound licentiousness, and inordinate vanity of that Vanity Fair.”

Like the “White City” itself, the Tabernacle was a divine theater where modern miracles could be seen and experienced. One wall was adorned with medical devices that were “captured from the enemy” when people were healed, a direct challenge to the modern wonders across the street.

Yet, this was not just a simple contrast between modern and divine miracles. The “White City” may have been the “dirtiest, filthiest hole upon God’s Almighty earth,” but Dowie was not immune to its belief in technological progress and innovation. After “several years of thought,” he ventured out to build his own, more lasting city: Zion.

While selling shares to his followers, Dowie proclaimed that the city would have “great paying industries,” and that “Brilliant inventors” were lining up to call Zion home. The city would have industry-leading harbor and freight facilities, linoleum-lined kitchens, direct rail service to Chicago, a telegraph office, telephones, and more.

If the written pitch was not enough, Dowie continually published images and news of the city’s development and exhibited 200 stereopticon pictures of Zion’s site and imagined images of its future.

In Zion, the profits of industry would be shared by all, and the products themselves would be salvific. The confectionery factory would make candies that make children healthier, the organ factory would produce sweeter-sounding instruments, the Zion typewriter would displace all other designs, and the lace factory would be five times more efficient thanks to its use of electricity. As Dowie himself mused, “ modern science, invention, and progress have made possible the establishment of a world-wide Theocracy.”

If Chicago’s White City was one techno-utopic vision of the future, we cannot ignore the ways that Dowie’s Zion was its imagined rival, a dreamscape of technological progress married to holy living, the ultimate answer to the industrial world’s urban problems. Technology and industry were note inherently evil, but raw materials which could be harnessed to achieve God’s ends. Zion was the city of the future, one that took the best of modern progress and rid it of its seedy underbelly.

Religion and the Techno-Utopic Imagination

In her recent book, When the Medium Was the Mission, Jenna Supp-Montogomerie argues that mid-19th century religious actors and institutions were vital for shaping the public sentiment and embrace of new network technologies, like the telegraph. By theologizing and narrating the importance of such inventions, religious leaders “helped make networks what they were and what they were imagined to be.” Likewise, those same leaders could help make sense of the distance between the rhetoric of technological progress and the realities of technological disappointment.

Zion was an example of this potent process of technological meaning-making. It was not just a religious fanatic’s techno fever dream or a complex securities fraud scheme (though not less). Rather, for most of its inhabitants, Zion was an answer to the pressing social questions of their day. In the face of social fragmentation, radical inequality, capitalist excess, and technological change, Zion offered a cohesive vision of the future that combined divine healing, social engineering, and technological progress. The world could be made right, at least in Zion.

This was an alternative vision of modernity, one that bound spirit to steel and prophecy to power plants. And while the social experiment of Zion may have failed, I am not so sure that its techno-utopic vision was as unsuccessful. As prominent pastors turn themselves into AI avatars, Christian outlets hail the potential of social media evangelism, and sermon preparation is outsourced to large language models, it seems like plenty of religious leaders continue to believe that these new forms of technology can be stripped of their less becoming outcomes and harnessed to work for the Kingdom of God.

[This is the first part in a three-part series, that delves into the story of Zion, Illinois, and its founder John Alexander Dowie. This series explores the oft-misunderstood relationship between charismatic Christianity and modernity.]