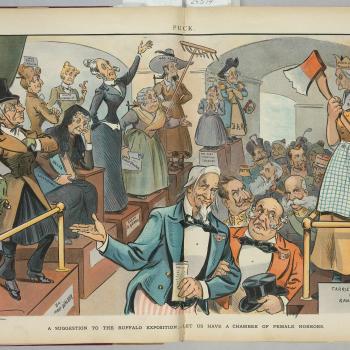

As I write about that amazing year of 1893, I have often used the language of new opportunities, new insights, even of liberation, and that was certainly true in some matters. White women, especially, vastly expanded their range of life-choices. But things were very different indeed for the eight million Black Americans who constituted some twelve percent of the national population. The years 1892 through 1894 were a dreadful time, which marked the decisive shift to a horrible new social and political reality. In some telling instances in those years, the two realities – optimistic White progressivism and desperate Black resistance – came into overt conflict. The affair highlights the ugly elitism and outright racism that undergirded at least some of the radical White reformism of the time – and its immersion in biological racial science.

Separate But Equal

By way of (very brief) background, through the period of Reconstruction, federal governments had sought to promote the full social and legal equality of newly freed Black populations, who at that stage were overwhelmingly concentrated in Southern states. The last Reconstruction regimes at state level collapsed in the pivotal year of 1877. However, the condition of Black populations and their legal status grew worse only gradually. For over a decade, many Black men continued to vote, and for a few encouraging years, Blacks allied with poorer White populations in broadly populist and anti-elite movements.

All images in this post are in the public domain

All images in this post are in the public domain

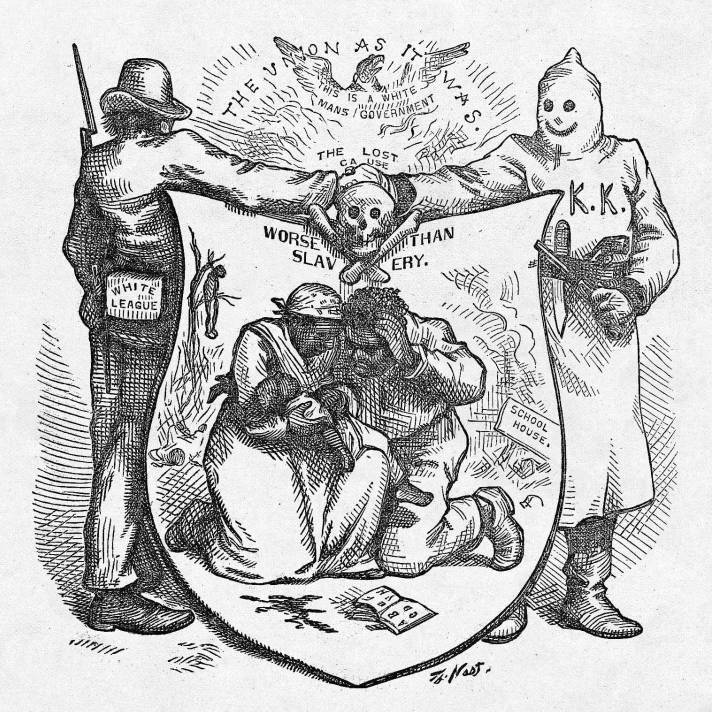

Matters then deteriorated sharply. Southern elites promoted a ferocious new ideology of unquestioned White Supremacy, tied to the creation of a carefully curated Lost Cause mythology. But this was not just a matter of nostalgia. The well-publicized advocates of a modern and industrializing “New South” agreed that Black Americans were unfit for any kind of self-government. The most famous tract in this tradition was The New South published by Henry W. Grady in 1890.

Black rights and voting power were systematically curtailed, as segregation laws became more commonplace and more strictly enforced. In 1892, Homer Plessy entered the “whites only” compartment of a New Orleans train in order to test Louisiana’s recently passed statute that commanded “separate but equal” provision for travelers. The resulting case resulted in the 1896 Supreme Court decision of Plessy v Fergusion, which thoroughly approved the separate-but-equal principle. This consecrated the Jim Crow society that remained in place through the 1950s.

The criminal justice system played an integral part in this new order. Although slavery as such certainly had ended, Black forced labor continued on a very large scale through the Convict Lease system, which supported much of the Southern economy. The system boomed through the 1880s and 1890s: by 1898, convict leasing supplied 73% of Alabama’s annual state revenue. Judges and law enforcement officials had a huge vested interest in arresting and imprisoning Black convicts, and for the longest possible sentences.

Although that leasing system does not survive in popular historical memory as egregiously as does lynching, the two were different sides of the same coin. In the words of an 1893 pamphlet, “The Convict Lease System and Lynch Law are twin infamies which flourish hand in hand in many of the United States. They are the two great outgrowths and results of the class legislation under which our people suffer to-day.” Even better, from the point of view of White elites, “Every Negro so sentenced not only means able-bodied men to swell the state’s number of slaves, but every Negro so convicted is thereby disfranchised.”

In a famous study published in 1954, Rayford W. Logan described The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877–1901, and that concept of “the Nadir,” the lowest point, is hard to avoid.

Lynching and Racial Crisis

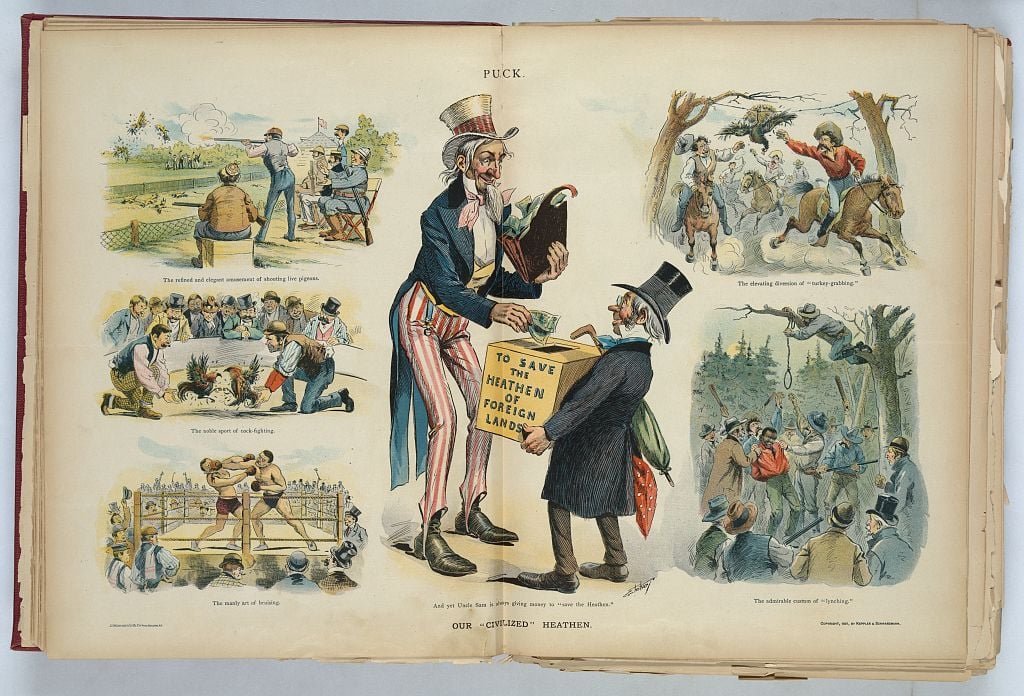

Throughout this process, the early 1890s repeatedly emerge as the period of most acute social and racial crisis, and this can be illustrated through hard figures.

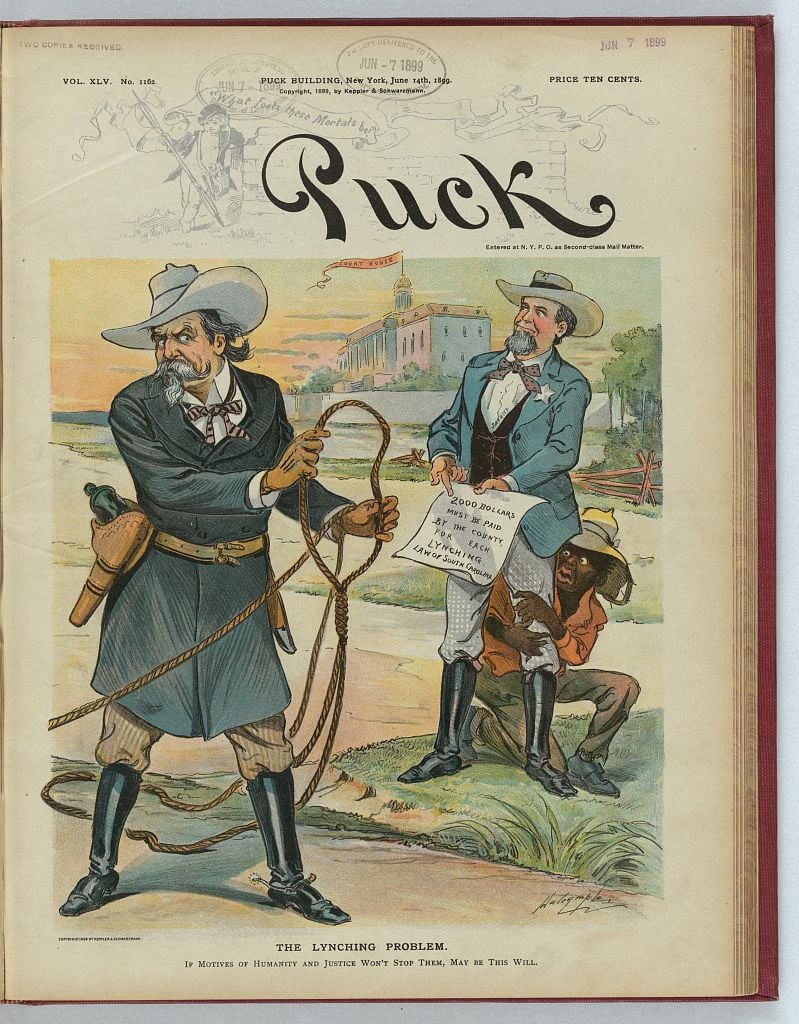

One excellent resource for American racial history is the catalogue of lynchings carefully compiled by the NAACP, which runs from 1882 through 1968, and which shows a grand total of 4,743 incidents: of these, around 75 percent involved Black victims. Now, this figure is a little misleading, in that we have no reliable figures for the years before 1882, and by all accounts, the 1870s were marked by appalling bloodshed. But if we just take the NAACP listing for what it is worth, it shows some critical patterns. Critically, the great majority of those 4,743 lynchings occurred between 1882 and 1901 – in fact, some three thousand cases. Also, by far the bloodiest period of all was the early 1890s. 937 of the total occurred just between 1891 and 1895, an average of 187 each year, or one lynching somewhere in the US every other day. The worst single year ever recorded was 1892, when 230 perished, of whom 160 were Black.

That fact alone has to condition any remarks that a historian might make about the arrival of modernity and Progressivism in the United States, all the new social ideas and spiritualities. A large share of the population was living in an environment of systematic (and intensifying) racial terrorism. To borrow the title of a famous sermon delivered by Washington Gladden in 1903, the country faced the problem of “Murder as an Epidemic.”

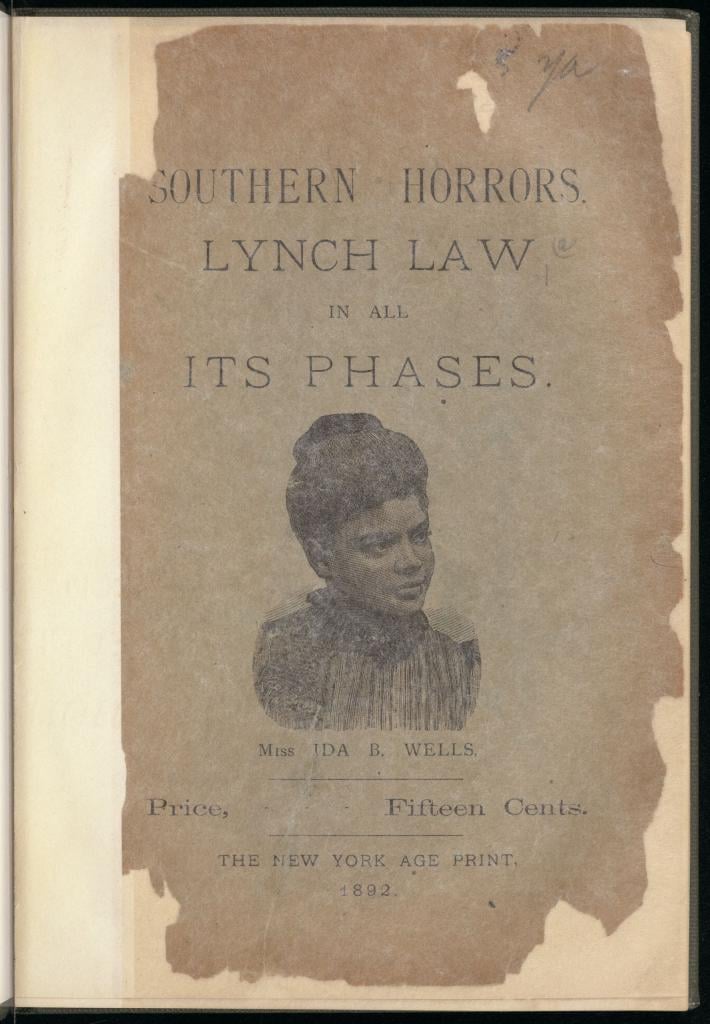

Ida B. Wells

Nor was there any reason why mainstream White America did not know of the ongoing situation. That desperate era inevitably produced its protests, but one author in particular stands out for her sweeping denunciations. Following a notorious lynching in 1892, Ida B. Wells began a detailed study of the phenomenon, which she rightly saw as fundamental to the racial regime of the New South. She is remembered as the author of Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892, and frequently reprinted) and in 1895, she published The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States. Each work in its way constitutes a foundational part of Black American literature, and of civil rights campaigning.

As all these books are available full text, I will not detail their arguments here, beyond some broad impressions. Wells was chiefly concerned with documenting and classifying the cases, and demonstrating the deep involvement of mainstream White politicians together with what she aptly called “The Malicious and Untruthful White Press.” Examining a thousand lynchings between 1882 and 1891, she found that alleged rape provided the motive in over a quarter of instances, but in most of those cases, the charges fell apart quickly upon investigation. Adding immeasurably to the horror of the crisis was the fact that mobs were moving beyond mere hanging to add forms of torture, mutilation and especially burning to the killings. She reported one case where the mob was less than sure of the charges that justified a lynching, and so decided only to hang the victim rather than burn him.

Black People and the White City

In 1893, Wells led a campaign to secure at least some Black involvement in the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, from which people of color had been almost entirely excluded. That activism is recorded in the widely-distributed pamphlet, The Reason Why The Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893), which included a Wells essay on lynching, and material by Frederick Douglass, as well as an exposé of Convict Leasing. But the movement failed:

Theoretically open to all Americans, the Exposition practically is, literally and figuratively, a “White City,” in the building of which the Colored American was allowed no helping hand, and in its glorious success he has no share….

In consideration of the color proof character of the Exposition Management it was the refinement of irony to set aside August 25th to be observed as “Colored People’s Day.” In this wonderful hive of National industry, representing an outlay of thirty million dollars, and numbering its employes by the thousands, only two colored persons could be found whose occupations were of a higher grade than that of janitor, laborer and porter, and these two only clerkships. Only as a menial is the Colored American to be seen – the Nation’s deliberate and cowardly tribute to the Southern demand “to keep the Negro in his place.” And yet in spite of this fact, the Colored Americans were expected to observe a designated day as their day – to rejoice and be exceeding glad. A few accepted the invitation, the majority did not. Those who were present, by the faultless character of their service showed the splendid talent which prejudice had led the Exposition to ignore; those who remained away evinced a spirit of manly independence which could but command respect.

They saw no reason for rejoicing when they knew that America could find no representative place for a colored man, in all its work, and that it remained for the Republic of Haiti to give the only acceptable representation enjoyed by us in the Fair. That republic chose Frederick Douglass to represent it as Commissioner through which courtesy the Colored American received from a foreign power the place denied to him at home.

Wells v. Willard

In earlier columns, I have discussed the quite radical gender activism that was so prominent a fact in these years, and which was concentrated in the Temperance movement as much as calls for women’s suffrage. But not for the last time in American history, such militancy operated within racially-defined blinders. Clashes between two quite separate world-views came to a head in 1893.

The central figure was veteran radical and feminist reformer Frances Willard (1839-1898), who from 1879 served as President of the major Temperance organization, the WCTU. In 1893, Willard was lecturing in Britain at the same time as Ida Wells was engaged in a quite separate tour. Wells used the opportunity to complain about the WCTU’s neglect of the lynching issue, and she offered as her prime exhibit an egregious commentary that Willard had offered in a speech in Atlanta in 1890. Willard had blamed the failure to implement Temperance on the “alien illiterates” who dominated Northern cities, and the presence of ignorant Black people made the situation even worse in the South. She went on,

It is not fair that they [the “aliens’] should vote, nor is it fair that a plantation Negro, who can neither read nor write, whose ideas are bounded by the fence of his own field and the price of his own mule, should be entrusted with the ballot. We ought to have put an educational test upon that ballot from the first. The Anglo-Saxon race will never submit to be dominated by the Negro so long as his altitude reaches no higher than the personal liberty of the saloon, and the power of appreciating the amount of liquor that a dollar will buy. New England would no more submit to this than South Carolina. ‘Better whisky and more of it’ has been the rallying cry of great dark-faced mobs in the Southern localities where local option was snowed under by the colored vote. Temperance has no enemy like that, for it is unreasoning and unreasonable. Tonight it promises in a great congregation to vote for temperance at the polls tomorrow; but tomorrow twenty-five cents changes that vote in favor of the liquor-seller. [My emphasis]

Southern Whites, she said, were good Christian people, but

The problem on their hands is immeasurable. The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt. The grog-shop is its center of power. ‘The safety of woman, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that the men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree.’ How little we know of all this, seated in comfort and affluence here at the North, descanting upon the rights of every man to cast one vote and have it fairly counted; that well-worn shibboleth invoked once more to dodge a living issue. The fact is that illiterate colored men will not vote at the South until the white population chooses to have them do so; and under similar conditions they would not at the North.

Willard attributed the sexual danger to drink, and also to the violence that characterized men – and specifically, Black men. Not one syllable of her statement differed from the common rhetoric used so often to justify lynching. Black men, in that view, were drunken and uncontrollable, and when freed from restraints they threatened girls and women. And in such situations, the proper response of outraged White “Anglo-Saxon” men should be … what, exactly, if not vigilante justice?

Wells, not surprisingly, was appalled, and there now began an embarrassing clash between two individuals, both of whom were lionized as progressive reformers. Willard countered Wells by alleging that she had launched an unprovoked attack upon all White American women, which she evidently had not. In a chapter devoted to the affair in The Red Record, Wells repeated “that in all the ten terrible years of shooting, hanging and burning of men, women and children in America, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union never suggested one plan or made one move to prevent those awful crimes. If this statement is untrue the records of that organization would disprove it before the ink is dry. It is clearly an issue of fact and in all fairness this charge of misrepresentation should either be substantiated or withdrawn.” Plausible answer came there none.

Désirée’s Baby, and The Pope

Given my present interests, I naturally focus on events and works that specifically derive from that year of 1893, and the concerns of the day are perfectly epitomized in the Wells-Willard controversy, and the agitation over the Chicago Exposition. I do have one other example, which admittedly is of a totally different scale of public impact. In that year, Kate Chopin published her much anthologized short story, “Désirée’s Baby”, which I will not summarize in detail because of its powerful plot twists: spoilers would be inappropriate.

The story concerns the ancestry and racial identity of a young woman in the Creole Louisiana of the Antebellum period. After so many decades of social and sexual interactions between the races, much uncertainty remained about those mixed identities, and the ultimate nightmare was finding that one might actually belong “to the race that is cursed with the brand of slavery.” Could you ever really know who was genuinely white, and who was just “passing”? That terror is the basis of the constant fears of interbreeding and miscegenation that were so central to the racial ideologies of the time in which the story was published, that is, of 1893.

I am a great fan of Kate Chopin, and it has been fascinating to see that story in particular acquiring something like a headline quality just recently. The new Pope, Leo XIV, traces his origins to a very similar Creole background, and his ancestors, FPC’s or “free people of color,” passed for White in a way that would have been thoroughly familiar to Chopin.

I like to think that when the present Pope was announced to the world, the ghost of Ida Wells was smiling contentedly.