I recently blogged about the radical feminist theories in religion that emerged during that critical year of 1893, the year of Matilda Joslyn Gage’s Woman, Church and State. But in other ways too, that same year witnessed other landmarks in women’s history, changes that profoundly changed mainstream politics and social thought. Apart from the obvious matter of the suffrage, I will talk about the revolutionary changes in approaches to Temperance, and to the protection of girls and women from sexual abuse. In all these areas, new Progressive movements transformed campaigns that had hitherto been defined in religious terms, and in so doing they changed the substance of American religious life. In both cases, the campaigns were so successful because they drew so heavily on new theories about biology and race.

All illustrations in this blogpost are in the public domain

All illustrations in this blogpost are in the public domain

Votes For Women?

Calls for women’s suffrage were nothing new in the 1890s, and if anything the existing movements were looking weary after several political defeats. In 1890, the two older-established organizations merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The most visible leader was Susan B. Anthony, but she was too radical for the developing movement. Appropriately for the point I am making about the trends in these years, it was a religious issue that sharply divided NAWSA in 1895, following Anthony’s involvement in publishing The Woman’s Bible, which I discussed recently. The group voted to disavow any formal connection with the book, to the horror of radical elements.

As a movement, NAWSA, together with the larger suffragist cause, really flailed in the next decade or so, and observers could well have been forgiven for dismissing the cause. Obviously it did succeed eventually, and advanced rapidly during the 1910s. But in understanding that survival and victory, we have to look beyond suffrage activism strictly defined but to other causes that very successfully mobilized women. And in both instances, the new movements grew out of the conditions of 1893.

The Anti-Saloon League

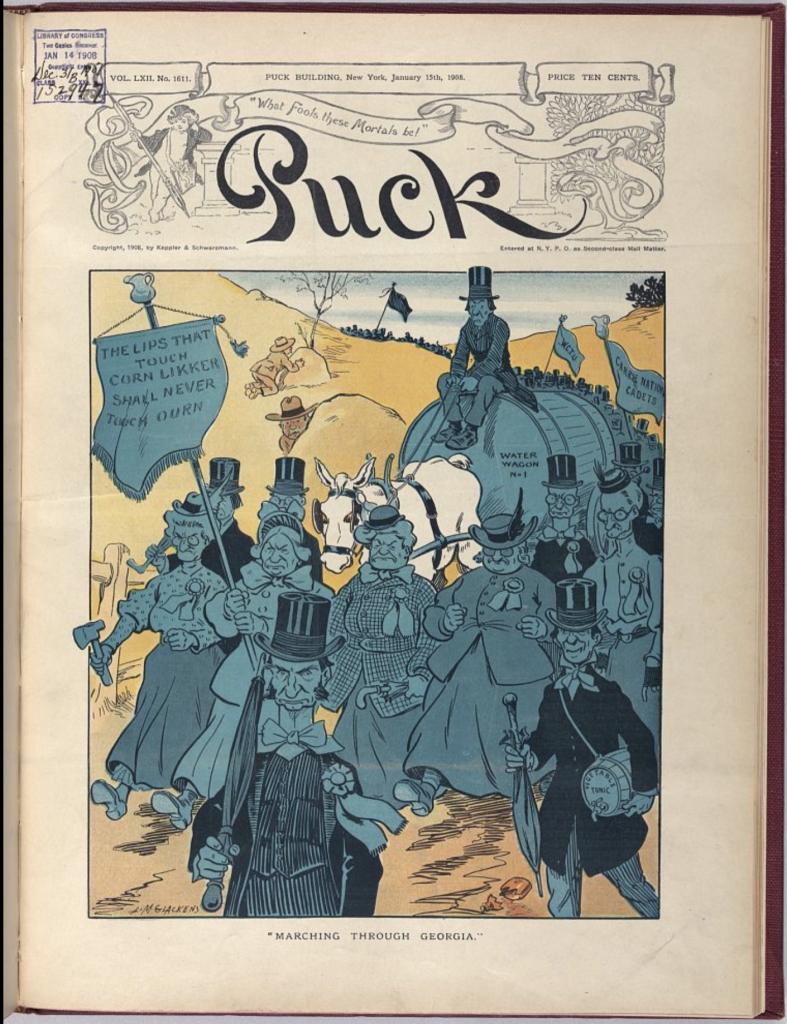

The Temperance movement likewise had deep roots, and already before the Civil War it was recording some legislative victories. At the end of the century, however, it developed a new militancy and one intimately linked to women’s causes, and the defense of women from domestic and sexual violence. In the history of Temperance, 1893 is so significant because it marks the creation of the Anti-Saloon League. I honestly cannot exaggerate the League’s significance in transforming an old-established cause into a modern national movement that politicians slighted at their peril.

Founded in Ohio (in Oberlin), by 1895 it had become a national phenomenon, and within a few years had totally surpassed the older groups, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Prohibition Party. It did an excellent job of integrating national militancy with grass roots organization, and in advancing local leaders. The group also relied on mobilizing religious activism, and its chief leaders throughout were Protestant clergy, mainly but not exclusively Methodists, Baptists, Disciples, and Congregationalists. Especially in the South and in the rural North and Midwest, the cause was a religious crusade. (Although the movement was often associated with the terrifying image of Carrie Nation and her vigilante hatchet, she was in fact an individual rogue entrepreneur).

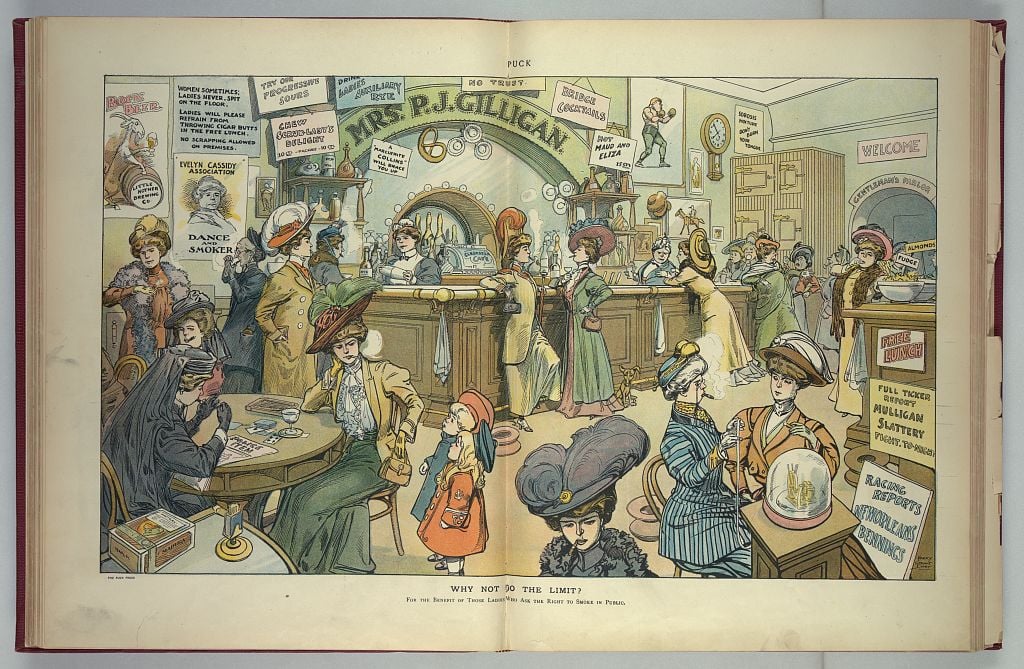

Although the first national leaders were men, women heavily dominated the cause. That brought many women into mainstream social and political life, with obvious implications for the continuing push for suffrage. Much of the movement’s propaganda focused specifically on the defense of women from drink-inspired violence and abuse. Drink was evil because of its threat to the security and well-being of families and the home – which in the context of the time chiefly meant to women.

The Anti-Saloon League was superb at what we might consider modern lobbying, paying close attention to the votes of political leaders, and its propaganda found its way everywhere. If you were a Protestant believer in the US of this time, you could hardly avoid League materials. Right up to the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1917, the Temperance story was mainly a matter of the League and its upward trajectory.

Gender Rights and Race

The evils of drink might be apparent, but in the context of the time, they were readily framed in racial terms. As I described in my previous post, biological and eugenic views of crime and social dysfunctions became very fashionable in the later nineteenth century, and it was very common to speak in terms of creating the most favorable conditions for breeding, of improving the (human) stock.

Those arguments combined easily with causes that in earlier times might have been understood as moral or religious in their nature. Eugenic activists were appalled at the havoc wrought by sexually transmitted diseases, for which effective cures were so scarce: for two generations, syphilis became an ultimate evil. Alcoholism was scarcely less devastating in its impact on heredity. Families devastated by drink and syphilis would inevitably breed inferior children who suffered hereditary diseases. All these arguments were readily adopted by feminist campaigns against prostitution and alcohol abuse. Sobriety and chastity were not just religious virtues, they were essential to the improvement of the race – and moreover of a race about to make its great leap to a new global imperialism.

These racial ideas were very frequently presented in the time, not just in mainstream newspapers and magazines but in the publications of churches, and of morality campaigns. They provided an essential and seemingly objective basis for the reform cause.

The Age of Exposé

From the 1880s, upper- and middle-class women led campaigns to improve the lot of the very poor, and commonly, they were driven by religious motives. The Hull House settlement in Chicago dates from 1889. But at the same time, they were reinforced by the scientific and racial theories of the time. Those diverse motives integrated in the social investigation of the era, and what would soon be named “muckraking.” Journalists, social reformers and others engaged heavily in exposing the lives of the poor, and as they observed the conditions around them, they became keenly aware of the extreme sexual dangers posed to girls and women, which they interpreted according to those new scientific understandings about sexual diseases and heredity.

In 1892, Rev. Charles Parkhurst exposed the sexual vice that was rampant in New York City, and tolerated by corrupt police and politicians. That activity included what we would call child prostitution, involving both sexes. Parkhurst’s exposés, and the ensuing investigations, dominated local media through the mid-decade. Another work from this era was W. T. Stead’s If Christ Came To Chicago (1894), with its detailed maps of vice areas in the city. These ideas were popularized in such fictional works as Stephen Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893).

Protecting Children

Young girls were very vulnerable, in societies in which the age of consent laws were incredibly lax. In 1885, the great majority of states still maintained the traditional English age-limit of ten years, while four enforced an age of twelve, but a widely popular social movement succeeded in raising those limits substantially over the next few years. In New York, the age was raised from ten to sixteen in 1887, and again to eighteen in 1895. By 1895, 22 states enforced an age of consent either sixteen or eighteen years, while ten more elected for fourteen years.

In these matters too, the landmark years were 1893-1894. In my previous column, I described the sudden appearance of criminology as a scholarly discipline in those years, and especially the almost overnight creation of a strikingly modern-sounding discourse concerning child sexual abuse and molestation. For present purposes, I stress how firmly such activism was rooted in women’s concerns and campaigns, and also to the Temperance movement.

In the 1890s, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union made the age of consent campaign one of its principal causes, to the extent that activists used the legal age in a given state as an index of women’s rights and status in that jurisdiction. Prominent in that movement were Mary Charlton Edholm, Helen H. Gardener, and Frances E. Willard, all leading advocates of women’s rights, and Edholm described female suffrage as the only way to combat the organized traffic in young virgins, “and its principal cause the gin-mill.” The inextricably interlinked movements against forced prostitution, white slavery, and venereal disease culminated in the federal Mann Act of 1910.

The great monument of this child protection campaign was Edholm’s much-reprinted book The Traffic in Girls, published in 1893 under the imprint of the Women’s Temperance Publishing Association: Edholm herself played a senior role in the WCTU:

In 1886, Edholm moved to Oakland, California and was unanimously elected official reporter for the WCTU; in 1891, she was named Superintendent of Press. Annually, she wrote about 250 columns of original temperance material for over 200 papers, including the dailies of San Francisco, Oakland, Portland, New Orleans, Boston and New York City, as well as The Union Signal and the New York Voice.

The Traffic in Girls largely describes missions among sex workers and “fallen women”, but a very large part of the material involves what we would call acts of child sexual abuse. Edholm’s assumption is that most such cases involve very early activity on the streets, from the ages of ten or twelve, which constitute a kind of training or initiation. Throughout, Edholm stresses the social and biological harm wrought by “loathsome diseases,” the need to reform age of consent laws, and argues that the problems could only be solved by women’s full social and political equality.

Once again, that strikingly brief period in the early 1890s marked a sweeping change in social consciousness. But as I will suggest next time, that grounding in biological and racial theory was potentially dangerous, and it ran the risk of lauding the interests of White and Anglo-Saxon groups as opposed to others, and above all, of the country’s very large Black minority

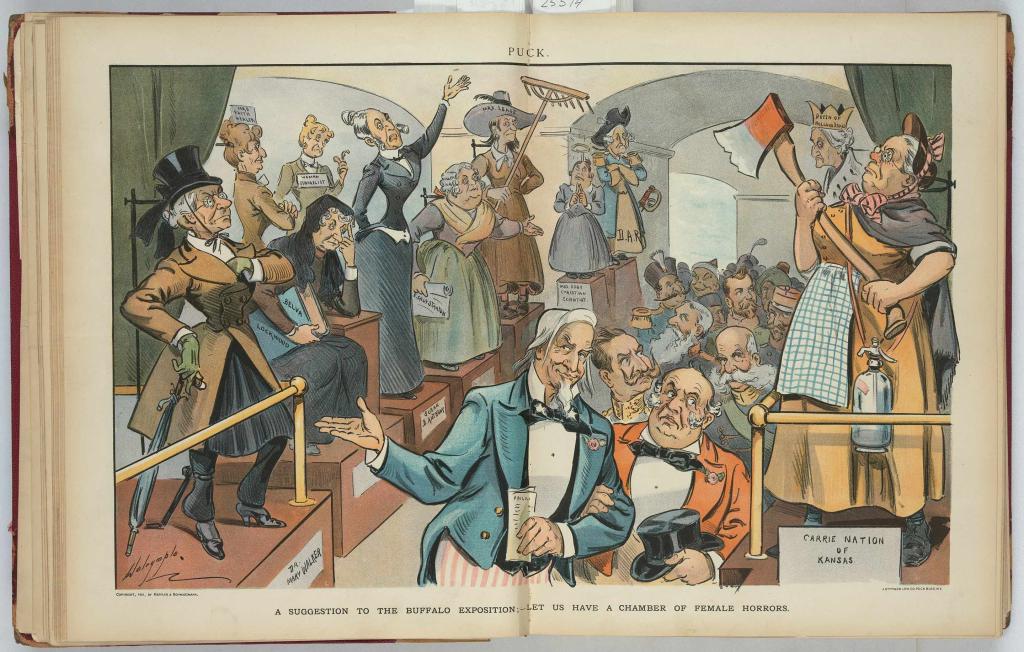

On a final note, I offer this anti-feminist cartoon from 1901, when the country was preparing for the Pan-American Exposition to be held in Buffalo. The cartoonist suggests there should be a “Chamber of Female Horrors,” including the most visible advocates for Women’s Suffrage and Temperance. I am struck by how many of the figures leading the movement for the liberation of women are broadly religious in character. We have Mary Baker Eddy of Christian Science, plus Elizabeth Cady Stanton of the Woman’s Bible, Temperance crusader Carrie Nation, as well as a generic “Mrs. Faith Healer,” and that ultimate horror, “Woman Evangelist.”