Have you ever used the words heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or masochistic? Or talked about sadomasochism? Have you ever expressed concern about child sexual abuse, or pedophilia? Then in linguistic terms as much as conceptual, you owe a sizable debt to a cultural revolution that occurred in the United States in and around the year 1893.

I have argued that the year 1893 marked several critical turning points in American history, broadly defined, and especially in matters of religion. This was also a time of quite radical innovations in understanding society and especially through studying deviancy, crime, and sexual misbehavior. Each in its way was seen as appropriate for scientific study and scientific solutions, belonging in the realm of the technocrat rather than the moralist or the preacher. In a very short period, Americans vastly expanded their understanding of such once unthinkable topics as homosexuality and sexual deviance, of child abuse and molestation, and much of the vocabulary we use to approach such issues stems from these times. In all these matters, we see the impact of new understandings of biology, which was so often bound up with racial nightmares. Of course, not all these tectonic changes occurred in a single year, but 1893 was central to something like a social and intellectual revolution.

A TRIGGER WARNING, SERIOUSLY. I never do such things normally, but in this case might I caution that some of the material below concerning sexual crime and abuse might well be upsetting? Read with care.

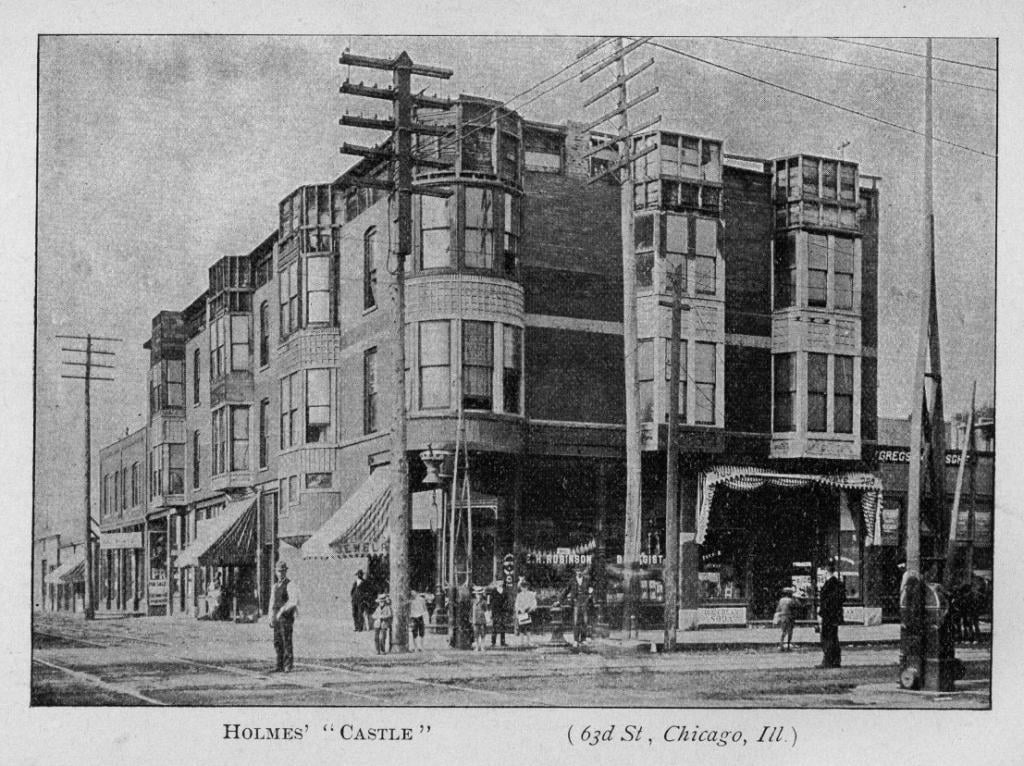

The Murder Castle

The most celebrated event of that year was the great World’s Fair held in Chicago, which was intended as a triumphant symbol of modernity, progress, and science, of America at its most glorious and expansive. Yet as so often, modernity had a Dark Shadow, in the form of multiple killer H. H. Holmes (Herman Webster Mudgett), who targeted women visiting the Fair, luring them to his notorious “murder castle.” His trial in 1895 was an international sensation. In modern times, the case is the subject of Erik Larson’s book The Devil in the White City (2003).

All illustrations in this blog are in the public domain

All illustrations in this blog are in the public domain

Many societies are fascinated by stories of True Crime, and serial killers are a perennial source of interest (even if that particular term would not be coined until the 1980s). But the Holmes case occurred at a time of unprecedented interest in various forms of criminality, and especially acts linked to mental illness or “degeneracy”. Was Holmes a true monster, or could science account for him? In the story of how people tried to answer that question, the short period between 1892 and 1894 was amazingly creative. The continuous history of American criminology dates from 1893.

Crime, Heredity and Eugenics

As Western societies urbanized and industrialized in the nineteenth century, many scholars and observers studied the crime and poverty that accompanied progress. Although they varied greatly as to the interpretations they offered, their work produced vastly more evidence of what we would today call underclass worlds. Initially in Europe, scholars increasingly offered biological and evolutionary explanations of these problems. (I discussed these trends in a recent blogpost). Particularly influential from the 1870s was the Italian scholar Cesare Lombroso, who argued that modern day criminals represented evolutionary throwbacks, which left unmistakable traces on their bodily features. Building on their understandings of Charles Darwin, British scholars argued for eugenic solutions, using selective breeding to stop social problems: if criminals and paupers were not born, then crime and poverty would vanish.

These ideas had powerful American manifestations. I have already discussed Richard Dugdale’s study of a multigenerational problem family in The Jukes: A Study of Crime, Pauperism, Disease and Heredity.(1877), but it was in 1893 that the new ideas became most powerfully apparent, when the Prisoners and Paupers of Henry M. Boies of Scranton. This offered a comprehensive eugenic and Lombrosan view of conditions in Pennsylvania.

Boies believed that crime, pauperism and mental deficiency were all increasing at a terrifying rate. In explaining these changes, Boies mentioned immigration, alcohol, and the devastating effects of modern urban life on the family and on morality, but his conclusions were thoroughly eugenic. Crime, pauperism and deficiency were the result of heredity, and all belonged to what Boies called “the imperfect, knotty, knurly, worm-eaten fruit of the race.” Perversion, alcoholism, crime, epilepsy and insanity, were all by-products of the “genetic rubbish” polluting the social gene pool, and which would stubbornly resist conventional legal solutions.

True ‘born criminals’ should be confined for life; but the real solutions were preventive. Boies attacked the “incomprehensible neglect of rational measures to restrict degeneration”, by which he meant sterilization. In summary, ‘The marriage of the criminal and defective must be prevented; and indeed, marriage of all those afflicted with constitutional defects should be prohibited.” In his later writing, such as his 1901 Science of Penology, Boies used an extreme Lombrosan and Positivist approach to crime, with a definite emphasis on the hereditary element in causing drunkenness, pauperism, disease, syphilis, murder, theft and prostitution.

Far from being an isolated crank, Boies was very well connected in the state’s administrative structure: he was a member of the Board of Public Charities, the Lunacy Committee and the Prison Discipline Society, all groups heavily influenced by the new ideas. Over the next twenty years, Pennsylvania was at the vanguard of sweeping legislation rooted in eugenic ideas, including provisions for sterilization.

Eugenic arguments of the most draconian kind even featured at the great World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. Texas doctor F. E. Daniel, editor of the Texas Medical Journal, delivered his paper, “Should Insane Criminals or Sexual Perverts be Permitted to Procreate?” He argued that

While we can not hope ever to institute a Sanitary Utopia in our day and generation, it would seem within the legitimate scope and sphere of Preventive Medicine, aided by the enactment and enforcement of suitable laws, to eliminate much that is defective in human genesis, and to improve our race mentally, morally and physically; to bring to bear in the breeding of peoples the principles recognized and utilized by every intelligent stock-raiser in the improvement of his cattle; and in my humble judgment the substitution of castration, as advocated above, for the useless and cruel execution of criminals, is the first step in the reformation. I predict that in twenty years the beneficial results of castration for crimes committed in obedience to a perverted (diseased) sexual impulse will be established and appreciated. Rape, sodomy, bestiality, pederasty and habitual masturbation should be made crimes or misdemeanors, punishable by forfeit of all rights, including that of procreation; in short by castration, or castration plus other penalties, according to the gravity of the offense.

Frontiers of Sexuality

Other scholars in these years were investigating the frontiers of the mind, and in so doing, they sometimes found “monsters.” In the 1880s, German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing had published widely on the fringes of sexuality, most notably in his Psychopathia Sexualis: eine Klinisch-Forensische Studie (Sexual Psychopathy: A Clinical-Forensic Study, from 1886. Among other things, this introduced such terms as sadism and masochism, and popularized the recently coined word “homosexuality,” together with “heterosexuality.” In 1892, neurologist Charles Chaddock translated the Psychopathia Sexualis, and in the process introduced those terms into English, along with “bisexuality.” Just having the words available, even if for experts only, transformed the intellectual discourse of sexuality.

Over the next quarter century, these theories were popularized by numerous scholarly and professional studies. Krafft-Ebing’s work inspired an outpouring of writing on sexual conditions and complaints, as American scholars developed their own taxonomy of sex-killers, pedophiles, and other sexually motivated offenders. “Perversion” suddenly became a significant social issue. In 1892-93, Max Nordau’s crucial book Degeneration was available to the many American scholars with access to German.

The problems facing society were evident, and whole new disciplines emerged to confront them. Arthur MacDonald’s influential text Criminology dates from 1893 (New York: Funk and Wagnalls): Lombroso supplied the introduction. The word “criminology” had been coined in Europe in the 1880s, and became commonplace in Italian and French, but MacDonald’s book popularized it in English.

Criminological themes entered popular culture. In 1893, Mark Twain was working on his Pudd’nhead Wilson, which appeared in print the following year. The plot depends on the idea of identification through fingerprints, an idea advanced by Francis Galton’s book Finger-Prints (1892). Although that point has no necessary connection with the eugenic themes I have discussed here, it was Galton who coined the word “eugenics”, and who was the best-known exponent of the theme in the contemporary world.

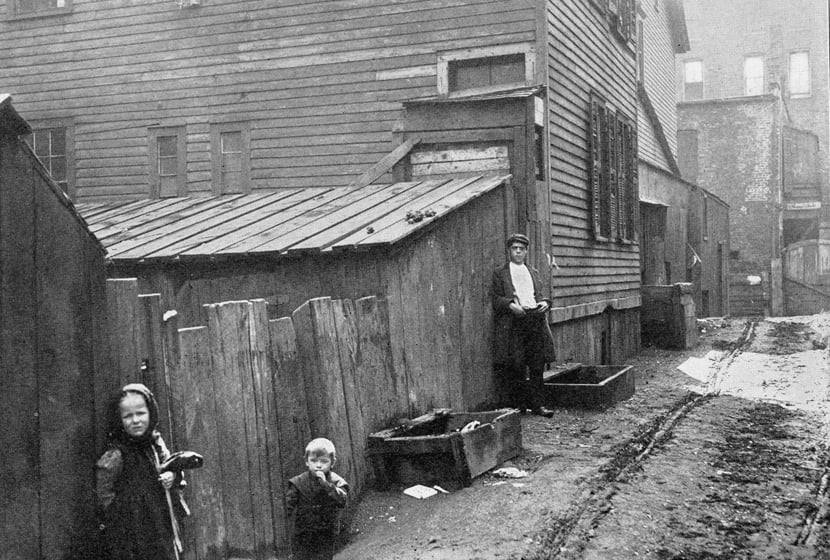

Saving Children

Social campaigners, feminists and eugenic campaigners alike stressed the desperate need to protect children from sexual violation – from what we would call abuse. (I will discuss the feminist context of these ideas at some length in my next post). In a very few years around 1893, something like a social and psychological science of child abuse and child protection appeared. In his 1893 book, Henry Boies complained that children “sporting promiscuously” in the streets, “where every foul nighthawk seeks its prey, lose the lovely innocence of childhood before they reach their teens.” Also in 1893, Mary Charlton Edholm published her frequently reprinted tract on Traffic in Girls which eloquently denounced cases in which preteen girls were molested by middle aged men. The perpetrators were “human gorillas, otherwise known as lecherous men.” The analogy uses the then-common idea of the gorilla as a vicious and supremely violent monster, and also nods to the Lombrosan idea of the biological throwback. (Again, I will have more to say about that author in my next post).

In 1894, a widely read textbook on A System of Legal Medicine edited by Allan McLane Hamilton and Lawrence Godkin included a pioneering account of “Sexual Crimes,” by Dr. Charles G. Chaddock, the translator of Krafft-Ebing. Reading Chaddock today, his work seems unsurprising and even obvious: who would ever have thought differently about such matters? But his ideas were revolutionary at the time, and they would repeatedly be forgotten and rediscovered in the United States over the following century.

Chaddock included sections on “‘rape’, ‘sexual abuse of children’, ‘sodomy’ (including ‘pederasty’, ‘bestiality’ and ‘tribadism’), ‘incest’, ‘exhibition / indecent exposure’ and ‘sexual perversion’.” This authoritative book initiated the whole American literature on child sexual abuse, and Chaddock used European statistics to suggest that “Rape of children is the most frequent form of sexual crime,” amounting to perhaps eighty percent of rapes reported to the police. This frequency was easily explained, as children were weak and vulnerable, while men were always in search of novel sexual excitement.

Can I cite that incredible sentence again? “Rape of children is the most frequent form of sexual crime.” When such statements were made again the 1970s and 1980s, they seemed to be wholly novel and startling, but they had a deep history. Remember that cliche about there being nothing new in the world except the history we have forgotten?

Other forms of exploitation noted by Chaddock included “sexual abuse,” defined as “sexual manipulations which are unrelated to the normal sexual act”. “Sexual perversion (erotic fetichism) might lead to an unnatural preference for children,” and arose from “constitutional psychopathic deficiency.” This is among the very first scholarly discoveries of pedophilia. The word pedophily appeared in English the following year, and in 1896, a new edition of Krafft-Ebing discussed the condition that he termed paedophilia erotica.

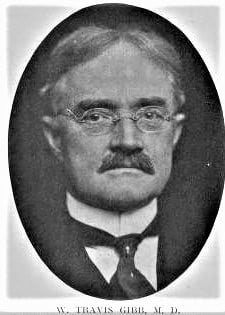

Dr. Gibb’s Revolution

The same System of Legal Medicine contained a trailblazing chapter on the “Indecent Assault of Children,” by the young gynecologist W. Travis Gibb, the very first study to suggest the prevalence of incest and molestation within the United States. Gibb was the examining physician for the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Children (NYSPCC), a charity formed in 1874 to investigate physical maltreatment and neglect of the young.

As child-savers explored the life of the slums, they discovered other evils: “Besides recognizing the constant presence of flagrant physical abuse of the type which led to this movement, new forms of protection have been recognized,” namely “that girls, while mere children and before they know what they are doing, invite or are unwillingly subjected to horrible abuses from men,” and catching “loathsome diseases” as a result. Gibb in fact was one of the first American medical experts, and probably the first, to realize that a young girl infected with a sexual disease was likely to have been assaulted, rather than catching it in some other way.

As all the cases observed involved poor and (often) immigrant children, the problem was taken to reflect the non-Protestant values of city-dwellers, leading Gibb to conclude that “The largest majority of cases… occur among the poorest and most depraved classes of people.” Gibb’s key insight was that molestation was a very common crime, and one which extended beyond the familiar image of men raping or seducing underage girls. Although “there is little or nothing in the medico-legal literature pertaining directly to the crime of indecent assault upon children,” The acts “occur much more frequently than is generally supposed,” and were “usually committed in secret and without witnesses.” Indecent assaults were committed by adult men against boys, and by women against either sex.

Assaults were perpetrated by “men who are insane, old men beyond the age of virility, men under the influence of liquor, and those suffering from some form of perversion of the sexual instinct which may be akin to insanity”. The damage resulting from abusive acts varied enormously from case to case, often causing no damage “beyond the moral,” but were sometimes so extreme as to cause death.

Such writings demonstrate the wide-ranging awareness of child sexual abuse that emerged so rapidly during the early 1890s – in historical terms, almost overnight. That is the definition of a revolution.

I talk about these issues at length in my book Moral Panic: Changing Concepts of the Child Molester in Modern America (Yale University Press, 1998).

Many years ago, when velociraptors roamed the Earth, I worked quite a bit on the history of American eugenics, and actually turned up some major undiscovered sources and archives on the topic: see my “Eugenics, Crime and Ideology,” in Pennsylvania History 51(1) (1984): 64-78.