Evangelical church camps found their ascendance in the twentieth century. The privilege of resort and camp life are portrayed in two cinematic depictions, Dirty Dancing and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. These depictions emphasize how resort and camp cultures were contexts to display class distinction and status, while simultaneously functioning as spaces for networking and cultural exchange. Both portrayals are set in an upstate New York Catskill Mountains resort.

Dirty Dancing is a coming-of-age story about Baby (Jennifer Grey), who comes from the home of a successful surgeon. Her father brought his wife and two daughters, Baby and Lisa, to camp for the summer. Lisa is obsessed with finding a match from among the elite resort staff hired from Ivy League schools. Baby seems content to be daddy’s girl until she meets Johnny Castle. Johnny (Patrick Swayze) comes from a working-class context. He is a young adult who teaches private and group dance lessons at the resort. Johnny harangues Baby for her privilege, while also revealing his self-aware insecurities about what separates his resort hand status from her privileged vacationer status.

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel series follows the meteoric success story of stand-up comedian, Midge (Rachel Brosnahan), who had been thrust into the status of self-supporting single mother because of the unfaithfulness of her husband. Midge comes from a wealthy, upper-Manhattan Jewish family. Her father, Abe Weissman (Tony Shalhoub), is a well to-do professor of mathematics at Columbia University and her mother Rose (Marin Hinkle) comes from Oklahoma oil money. The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel includes a series of episodes where Midge accompanies her parents on their annual two-month summer camp retreat to a Catskills resort. In these episodes, Midge is matchmade to Benjamin Ettenberg (Zachary Levi), a successful surgeon and desirable bachelor, while her talent manager, Susie Myerson (Alex Borstein) poses as a resort hand to keep prompting Midge to pursue her career as a stand-up comedian. Myerson’s character in the show is portrayed as a rough around the edges, working-class woman who lacks refinement. Her role as camp plumber, with plunger always in tow, matched how she was otherwise perceived.

While these two depictions of the privilege of summer resorts are not distinctly portrayals of evangelical church camps, they are faithful to the wider cultural phenomenon that is equally applicable to Christian contexts during the same era.

The Rise of Christian Leisure Culture

Again, it’s essential to highlight that these are spaces that represent one’s privilege and luxury. You see, evangelical church camps and resorts emerged in an era that emphasized the value of leisure time, holiday, and vacation. To retreat and camp meant one had the privilege and luxury to break from work and pursue leisure.

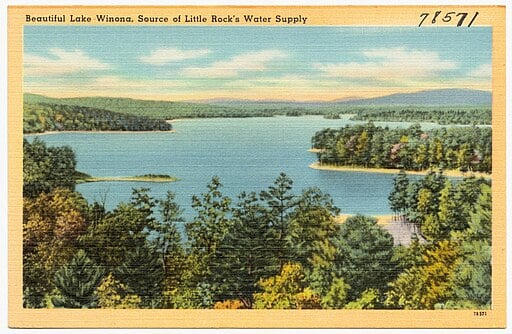

An evangelical family went on holiday to a place like Niagara or Lake Winona not just because that place hosted a bible conference on premillennial biblical interpretation or a study of a prophetic book of the bible, but because it symbolized something about what the family head had accomplished. This family had achieved a certain status and now they got to enjoy it. And throughout their week of camp, they would be able to share with others from around the country what they’ve achieved in life while also engaging in intense biblicism. These family heads, spouses, and children networked among one another and imparted to one another the secrets or latest trends of suburban life and status.

Too rare do we think about how evangelical identity entails privilege, and access to privilege and luxury has always been necessary for evangelicals to create and consume their own culture.

Consider the annual cycle of consumption for a common suburban evangelical family. A nuclear unit that includes a husband, wife and two children will engage in all sorts of evangelical activities in a given year. Men’s retreats, women’s conferences, vacation bible schools, summer camps, mission trips—all these evangelical activities have price tags attached to them. Some of them are quite expensive. The suburban world already applies an inordinate pressure to keep children busy all summer and evangelicals support this endeavor by offering ministries to occupy suburban families’ time.

If you’re an evangelical, you know what I mean. And I bet if you open your closet or pull out a dresser drawer you will have numerous tees that chronicle your experience of evangelical church camp. You may have been a creator or brand ambassador for the evangelical church camp merch in your closet. Some among you may have had a loving mother fashion all your evangelical church camp merch into a patchwork quilt that catalogued your experiences.

All of those experiences required some level of privilege or luxury. Whether that privilege included a parent writing a check for that activity, your own time to fundraise for the ministry, or access to scholarship funds that enabled you to be involved.

In the 90s and early 00s, a weekend retreat might have been $75-125, and evangelical church camp could have been anywhere between $350–550. These days weekend retreats commonly start at $150 and push to $350. Evangelical church camps will start at $550 and skyrocket to costs of $1,500–2,000 depending upon the caliber of program, length of camp, and location of venue.

Throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first century numerous evangelical church camp systems have existed to spiritually convert, educate, and train children to college age students for Christian ministry. Some well-known evangelical church camp systems include YoungLife, Word of Life, Intervarsity, Kanakuk, and Student Life. I’ve been associated with many standalone camps that come to mind as well: Pine Cove in East Texas, Silver Cliff Ranch in Buena Vista Colorado, New Life Ranch in Siloam Springs Arkansas, Expeditions Unlimited in Baraboo Wisconsin, HoneyRock in Three Lakes Wisconsin, Lakeside Bible Camp on Whidbey Island, Washington.

These camps found across the United States are not public spaces for public consumption, though many of them stand adjacent to our national and state park systems. Rather, they are private, set apart spaces–dare I say holy spaces, devoted to the exclusive privilege of fostering Christian devotion.

And yes! Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century, these evangelical church camps have adapted to survive a competitive environment by availing their assets for the use of non-Christian paying customers, such as corporate retreats, accessibility camps, and social interest groups. Some evangelical church camps have experienced financial crisis causing them to sell off land, facilities, locations or close altogether (Camp Timberlee, EFree/TIU). Others have been locations of employment for predators of terrible abuse (Kanakuk Camps) or places subject to horrific natural catastrophe (recently Camp Mystic, Kerr County Texas).

Evangelical habits of mind were formed at evangelical church camps, and these environments are where root memories occurred. Camp may be where you experienced a spiritual conversion or vocational calling. It may also have been the birthplace of romance, a place for a first crush, love, or where you met your future partner. Sadly, icky feelings come from camp, too. They have been locations for abuse, bullying, camp drama, even church splits. Social lessons accompanied spiritual lessons at church camp.

Nonetheless, occupying and accessing these spaces always has required some level of privilege, luxury, and leisure—which also means that many have faced barriers to accessing these experiences. If a historic characteristic of conservative Christian Protestantism is the Protestant work ethic, it is also true that this characteristic is one that has opened doors of access to Christian experiences for some while creating friction to access of those same experiences for others. H. Richard Niebuhr aptly noted, “[If] one of the marks of culture is that it is the result of past human achievements, another is that no one can possess it without effort and achievement on his own part” (H. Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture, 33).