Much of the commentary about John MacArthur in the wake of his death last week has focused on the controversies about his views on gender and politics or his habit of turning a deaf ear to women who complained about abuse from their husbands or church leaders. But few people have asked the question of what made MacArthur popular to begin with.

MacArthur was not a charismatic preacher in any sense of the word. As a cessationist, he was certainly not a charismatic in the theological sense; he believed that miraculous gifts ceased after the first century. But he also lacked charisma in the colloquial sense of the word. He delivered his sermons in a relatively monotone voice. He was not a storyteller. He didn’t make sensational claims or attempt to make his messages entertaining. Instead, he began each sermon by reading from the Bible, and he then followed that with a bullet-point list of applications from the passage, often extending for up to 50 minutes with hardly any illustrations or breaks from the tightly focused biblical exegesis and exhortation.

But somehow it was amazingly popular. Shortly after MacArthur became pastor of Grace Community Church in Los Angeles in 1969, the church began doubling in size every two years. Eventually, it became a church of 8,000 people, with the 3,500-seat auditorium filling to capacity for the church’s two Sunday services each week. But MacArthur’s influence extended far beyond his own congregation. His “Grace to You” broadcast was carried on more than 1,000 stations and, according to the ministry’s own figures, reached more than 2 million people each week. Some of MacArthur’s 400 books and study guides – along with his more than 3,000 sermons – were translated into more than two dozen languages.

I suspect that the reason for MacArthur’s popularity was the hunger many people had for expository preaching. MacArthur was certainly not the first expository preacher, nor was he the only one in existence in the 1970s, when his preaching career began taking off. But at the time, expository preaching in the way MacArthur practiced it was not very common in the American evangelical Baptist world, and MacArthur’s version of it was therefore lifechanging for many people who heard it for the first time.

Nearly all of MacArthur’s sermons functioned as application-oriented commentaries on the biblical text. He began with a passage of scripture, explained its original meaning using the historical-grammatical method of interpretation, and then drew applications from it that he thought were relevant for his contemporary audience. And each sermon built upon the previous one, since he preached through books of the Bible systematically. He spent ten years preaching through Romans, and then made his way through the rest of the Bible at a considerably faster pace. By the time he died last week at the age of 86, he had preached through the entire Bible during his 56 years of pulpit ministry.

Today this method of preaching might seem familiar to anyone who knows about the sermons of John Piper or Tim Keller – or, for that matter, nearly any contemporary pastor in conservative Presbyterian or Reformed Baptist circles. But at the time that MacArthur began preaching, it was not nearly as common.

Expository preaching had been a hallmark of the sixteenth-century Reformed tradition. This was especially the case for John Calvin, who preached many long series of expository sermons that systematically exegeted multiple books chapter-by-chapter or section-by-section, with sermon series on Genesis, Deuteronomy, Job, Acts, Galatians, and Ephesians, among others.

But in eighteenth-century Puritan New England and Anglican old England, systematic expository preaching gave way to text-based sermons that were designed not to exposit a passage of scripture but rather to prove a thesis. Rather than preach through an entire book of the Bible systematically, a minister might instead take a particular Bible verse that he thought would be especially applicable to his audience’s situation and then expound on that theme for an hour, first by introducing a question or argument, and then by proving that argument over the course of the sermon with reasoned deductions and additional scriptural examples presented largely without context.

For example, George Whitefield’s sermon “The Necessity and Benefits of Religious Society” began with the scriptural text for the sermon – Ecclesiastes 4:9-12, which includes the key phrase “Two are better than one.” In accordance with the conventions of an eighteenth-century sermon, Whitefield then announced the particular assertions that his sermon would prove:

“First, The truth of the wise man’s assertion, “Two are better than one,” and that in reference to society in general, and religious society in particular.

“Secondly, To assign some reasons why two are better than one, especially as to the last particular. . . .

“Thirdly, I shall take occasion to show the duty incumbent on every member of a religious society.

“And Fourthly, I shall draw an inference or two from what may be said; and then conclude with a word or two of exhortation.”

While Whitefield did circle back to his opening passage at times, he also sprinkled numerous other scriptural citations throughout his sermon, with references to Adam’s loneliness in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2), Paul’s association with the disciples in Acts 9, and Jesus’s relationship with his disciples in the gospel of John. He made little if any attempt to exegete Ecclesiastes 4 in the larger context of the writer’s message. He gave no hint that his sermon was in any way connected with a larger sermon series on the book of Ecclesiastes; most likely, it was not. And his main point was one that would not have been familiar to Ecclesiastes’ original author; it was the argument that Christians needed to be intentionally active in “religious society,” since they needed Christian encouragement.

Whitefield’s sermon was a typical example of eighteenth-century preaching; it accords well with other sermons I’ve read from that century, which is why I selected it. In one sense, eighteenth-century preaching was still expository – but not in quite the same way that Calvin’s was. Rather than systematically preaching through books of the Bible with the primary goal of helping a congregation understand the text and apply it to their own lives, ministers of the 18th century were more apt to isolate biblical passages from their larger context and to mine them for particular phrases that could be applied to a contemporary situation.

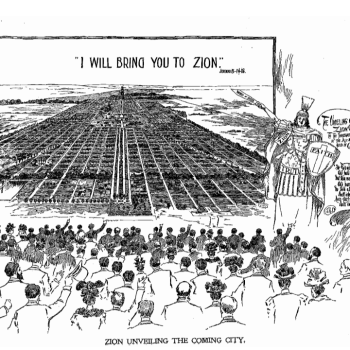

That is how, for instance, the New England ministers of the 1770s could preach so many sermons justifying the creation of a republic and the revolt against the British monarchy; even though the Bible didn’t deal directly with late eighteenth-century politics, there were plenty of biblical verses which, if taken in isolation, could be promising texts for a political sermon.

Nineteenth and twentieth-century revivalist sermons popularized a new style of preaching – the conversational style, with a focus on anecdotes designed to bring a person to conversion. Dwight Moody’s sermons were filled not with biblical exegesis but with stories and fictionalized dialogue designed to bring sinners to Jesus. Billy Sunday’s sermons featured a lot more shouting and theatrics, but were otherwise a lot like Moody’s in format: They were filled with anecdotes and fictionalized dialogue that he thought would keep his audience’s attention and cultivate the emotions needed to induce conversion. Moody often began his sermons with a brief reference to a supporting text, but Sunday sometimes dispensed even with that perfunctory introductory scripture reference and instead organized the sermon around a topic – which, in many cases, was closely related to his signature campaign against alcohol.

Outside of the revival circuit, topical sermons became very popular among pulpit ministers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. So did sermons that riffed off a single short phrase of scripture that could easily be broken down into a three-point sermon – sometimes presented without much regard to the verse’s larger context.

One website advocating this style of preaching explains how to write a sermon on Ezra 7:10. The verse says, in the words of the KJV: “For Ezra had prepared his heart to seek the law of the Lord, and to do it, and to teach in Israel statutes and judgments.” In the view of some twentieth-century preachers using the text-based approach to preaching, this verse made an ideal three-point sermon: Christians needed to “seek” God’s word; they needed to “do” the things stated in God’s word; and they needed to “teach” God’s word to others. If the sermon was filled with enough anecdotes, exhortations, and other scriptures illustrating each of these three points, it could easily fit into a 30 or 35-minute time slot.

When MacArthur began preaching in 1969, Baptist churches were used to this style of preaching, along with its close cousin, the topical sermon. Both were focused heavily on application. Both claimed to be based on the Bible. But neither type of sermon was particularly effective in giving congregations the tools of biblical theology – that is, to see how each book of the Bible related to the larger overarching theme of God’s redemptive story.

Expository preaching, on the other hand, could do that. Usually, the best known among the expository preachers of the late twentieth century – such as David Martyn Lloyd-Jones, for instance – started by going through the book of Romans verse by verse and developing the Pauline framework for understanding all of scripture through a Christ-centered lens that focused on the need for redemption and the realization of God’s grace in Jesus’s atoning sacrifice. They then used this hermeneutical lens to preach through the rest of the Bible chapter-by-chapter.

The result was spiritually electrifying when MacArthur brought this Reformed expository preaching style to community church members and Baptists who had never heard it before. For the first time, they were able to see the Bible not as a set of isolated principles but as an interconnected story of humans’ need for grace and God’s provision of salvation. They were acquiring a biblical theology – and, in their view, it was emerging organically from the text rather than being artificially imposed on the Bible as an outside system. They became excited about Bible study, because they could now see what the Bible was all about.

In my opinion, expository preaching was a central reason for the sudden rise in popularity of Calvinist (or Reformed) theology among conservative evangelicals during the past thirty years. Evangelicals who grew up hearing sermons that danced around the biblical text but never exegeted biblical books systematically were excited to finally hear the Bible preached through in its entirety in an orderly, logical fashion. Some of them were so attracted by this message that they left their non-Calvinist churches and joined Reformed congregations that featured expository preaching.

I don’t think that the evangelicals who converted to a Calvinist theology were initially attracted to Calvinism because of its logic or principles; I think that they instead came to believe it because they thought it was biblical. And in many cases, they initially came to believe that it was biblical because they saw Calvinist theological principles emerging from the expository sermons they heard from their favorite expository pastors – all of whom were Calvinists.

If most of the pastors preaching expository sermons are Calvinists, we shouldn’t be surprised if people who are hungry to hear God’s word preached exegetically and systematically will naturally gravitate toward Calvinism and view the Bible itself as a Calvinist book.

That was the secret of MacArthur’s success, I think. For all his faults – some of which, I admit, are glaring – he gave people a steady diet of expository biblical preaching. I hope that some of those who are critical of MacArthur and his theology will offer some expository teaching of their own – because unless they do, people who are hungry for a systematic study of the word of God will continue to flock to any pastor that provides it, regardless of the pastor’s flaws.