On a recent trip to Turkey and Greece, where I loved the churches, mosques, and museums we were able to tour, my daughter had a very different highlight for her trip: the feral cats found in abundant number everywhere we went. While these cats marked every stop on our trip (much to her delight), on Cyprus, these cats came with a fascinating story that overlapped with church history, much to my delight.

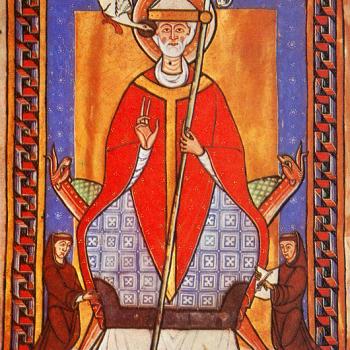

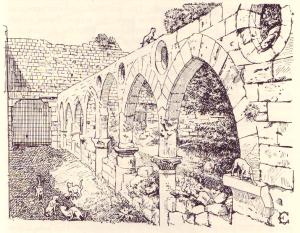

According to legend, Helena, the mother of Constantine, stopped on the island of Cyprus as she returned from her pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 328. When her ship landed, Helena was alarmed to find that the entire island was overrun with venomous snakes, and that the Cypriot residences were suffering. Helena came up with an ingenious solution: she sent a shipload of cats (or, in some tellings, several shiploads, containing around one thousand animals) to Cyprus to hunt the snakes, putting the cats under the care of a recently founded monastery of which she became patron. The monks were responsible for feeding the cats a bit of meat each morning and evening to help the cats counter the venom from the snakes, but otherwise, the cats sustained themselves by hunting and killing the snakes until the snakes were gone and no longer a threat to Cyprus’s residents. The monastery even had two bells: one for calls to prayer, and one for calling the cats into battle against the snakes. St. Nicholas of the Cats served in this role until the island’s conquest by the Ottomans in 1570, but was reestablished in 1983 as a convent, where the nuns still care for the cats (complete with some government support for the food for the hundreds they serve each day).

Legends and (Lack of) Sources

When we first heard this story, we were charmed by the connection to Helena and to the early church. Upon returning home, I immediately started trying to verify the account, looking for primary sources to help collaborate one of my new favorite anecdotes from early church history. And while it does seem cats and Cyprus have a long history, the verifiability of this account is not as a historian would hope. A study by French archaeologists did find that Cyprus, not Egypt, was home to the earliest known domesticated cat. And there are indeed so many cats on the island that the cats of Cyprus are their own distinct, recognized breeds. Helena’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land to find the true cross is well-documented in early church historians Eusebius of Caesarea and Rufinus of Aquileia, as well as in Ambrose’s later account, but her stop on Cyprus is not mentioned in any of these. It’s geographically possible (perhaps even probable) that she stopped there, but not verifiable in the written record. And none of these more contemporaneous sources mention the cats and Helena’s involvement in dealing with the island’s snake problem, although several late medieval and early modern chronicles and travel writings do at least mention the cats, notably Dominican Father Stephen de Lusignan’s 1573 and 1580 writings on Cyprus.

Looking more broadly, the history of Cyprus is incredibly well documented, with chronicles, letters, histories, and other sorts of written sources supplementing the archaeological record from the Bronze Age through the Roman, Byzantine, Crusade, and Ottoman periods to the present. There are so many records that numerous more modern scholars wrote comprehensive histories of the island, like Sir George Francis Hill’s four-volume History of Cyprus (1940-52). Notably, in Hill’s history, a governor serving under Constantine, Calocaerus, gets credit for sending the cats to solve the snake problem, and Helena is not mentioned at all (Hill, The History of Cyprus, vol. 1, p. 244). But the accounts that Cypriot residents share are unanimous: the cats, known colloquially as St. Helen cats, are the legacy of Helena’s creative problem solving.

Lessons from the Legends

While not historically verifiable, I do think that this anecdote has some fun illuminating points for us to think through. First, it illustrates one of the common problems we run into when studying women in church history: their actions are often rendered invisible in the historical record or attributed to men. None of the written sources about the history of Cyrpus in the 300s connect Calocaerus to the advent of the island’s numerous cats: and yet, Hill confidently assumed that the man in charge must be the one who took action. It’s a good reminder to look outside of the usual chronicles and textual sources as we look for women in the church. Listening to the congregations and people they served (even if what we learn from them cannot be fully proved in written documents) can often better point us to their work, legacies, and impact.

And it does seem that sending boatloads of cats to help the residents of Cyprus is something that Helena would do. My colleague and husband Adam Renberg’s post on Helena highlighted her charity: the way in which she used her privilege and power to serve. Eusebius noted how “She made innumerable gifts to the unclothed and unsupported poor, to some making gifts of money, to others abundantly supplying what was needed to cover the body. Others she set free from prison and from mines where they laboured in harsh conditions, she released the victims of fraud, and yet others she recalled from exile” (Eusebius, Life of Constantine III.44). Rufinus noted that on her pilgrimage, Helena acted as a servant to the consecrated virgins, serving them lunch and washing their hands (Rufinus, Church History, 10.8). In short, Helena seems to have made a habit of serving people according to their most pressing needs as a way of living out her faith. In most situations, that would not have looked like sending 1,000 cats to someone, but this creative charity certainly aligns with the other forms of charity (like freeing the victims of fraud) that we do have documented. This gestures to a second point to ponder: are we, like Helena, being creative enough in how we meet the needs of those around us? Church history is full of these examples of creative service (although I have to admit I don’t know of many others involving this many cats). What might the venomous snakes in our communities be– and are we hiding from them or, like Helena, finding ways to literally combat the problem? Our solutions may not involve boats of felines, but who knows– that may indeed be what we need.