“The task of city design involves the vaster task of rebuilding our civilization.”

Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities

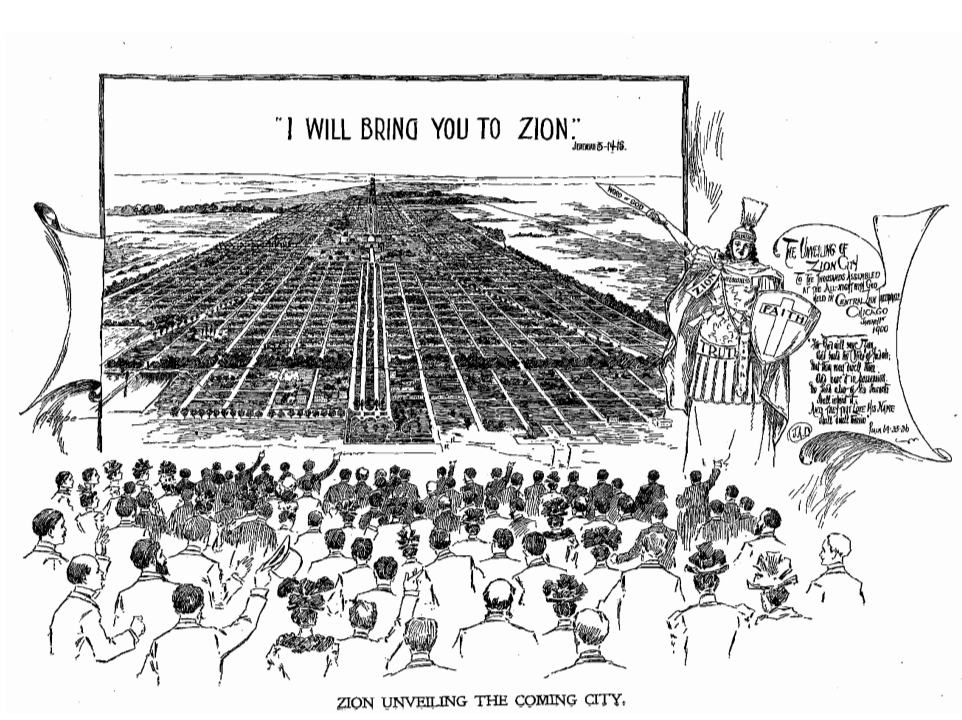

In the wee hours of the morning of January 1, 1900, civil engineer Burton J. Ashley stood among hundreds of his brothers and sisters in Zion Tabernacle. They were tired from the all-day consecration service that had begun at 6:30 a.m. on the previous day. Ashley, however, felt energetic. His moment had come.

Just before the pause for refreshments at 2 a.m., the “concealed mechanism” behind the stage slowly began letting down a giant map of Lake Michigan and its surrounding environs. At its center, lit by the glow of an electric light, was a single dot and the bold letters “ZION.” Then the “brilliant rays of a calcium searchlight” flashed into life, lighting the screen so all could behold the location of the Coming City—a site chosen by Ashley. Dr. Dowie took to the stage with an electrified pointer to explain the map in detail, and when he finished, another map miraculously unfurled itself. This time, a detailed diagram of the Coming City’s streets, institutions, and gardens—a design created by Ashley. And when Dowie’s explanation had run its course once again, a final great image unrolled, an enormous painted vista of that Coming City—a vision that had, up to then, only lived in Ashley’s mind.

Thunderous applause shook the building as Ashley made his way to sit at the front of the platform.

Born in 1857 in Sparta, Ohio, Burton J. Ashley was not on a course to become the visionary behind one of America’s most memorable utopian experiments. By 1900, Ashley had made a name for himself through a distinguished career in engineering. Serving for six years as the county engineer for Morrow, Ohio, Ashley relocated with his family in 1880 to the booming city of Chicago. Still rebuilding from the fire of 1871, the city was intent on creating a modern city with civic regulations and building codes that would ensure such a disaster would never occur again. It was a dream for engineers on the make, and one that only became better as the city prepared for the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Ashley served as the arbitrating engineer for the fair’s Casino Pier and the superintending engineer for the World’s Congress Auxiliary Building, today known as the Art Institute of Chicago. It was a career any engineer would envy, but its future lay further down Michigan Avenue.

By 1895, Ashley had been drawn into the orbit of J. Alexander Dowie, the famous faith healer. Reportedly, his daughter had been healed at a Zion Tabernacle service. Perhaps hoping to pay his debt, Ashley served as a secretary that year for a meeting dedicated to defending Dowie against several public lawsuits. In 1897, he joined the church and was quickly drafted into efforts to establish Zion City.

As Dowie invited Ashley to address the crowd at the unveiling, he confessed his own lack or oratory skills, but assured the crowd that, “As soon as I was appointed to this position, my mind at once began to look toward the matters of reform that are necessary in the building up of a city.” His simple commitment echoed the Zion Land and Investment Association’s objective of making all “public improvements needful in establishing a large, clean and enterprising Modern City.”

Ashley’s desire to build a modern city might stand out for its religious context, but not for its content.

Garden Cities and Company Towns

As discussed in the last post, by the late-19th century, the industrialized world was reeling from the social upheavals of the Second Industrial Revolution. Along with economic growth, the rapid rise of industry has brought urban hellscapes where cesspools and disease were married to crushing poverty and industrial disasters.

Everyone knew there was a problem, and many sought to fix it. Socially and economically-minded industrialists arrived first on the scene. Marrying reform with the theories of scientific management, titans of industry built entire new towns for their workers, replete with good schools, public gardens, well-designed homes, and public utilities. Model towns like Pullman, Illinois, or Kohler, Wisconsin, were meant to provide all that workers needed; the theory being that happy workers enhanced efficiency and led to greater profits.

Yet, these company towns were costly experiments in suburban living and could not solve the pressing crisis of the city. In stepped legions of urban planners and engineers who began searching for attainable alternatives.

Perhaps the most famous was Ebenezer Howard, the father of the Garden City movement, founded in Britain in 1899. Howard’s ambitious plan reimagined a new relationship between town and county where urban industrial centers would be surrounded by planned suburban townships and everything would be connected by rail. In America, the idea wedded itself to the automobile and gave rise to the modern suburb.

Still others sought to save the city itself. Within the City Beautiful movement, men like Frederick Law Olmsted and Daniel Burnham wanted to “[vivify] the national desire for civic beauty” by populating cities with grandiose architecture, public parks, and grand urban vistas, all towards the goal of fostering a greater sense of civic responsibility and an enlightened citizenry. Daniel Burnham served as the chief architect for the Chicago’s Columbian Exposition and the Chicago Plan, both of which became crowning achievements of the movement and a vision of what could be.

Ashley’s Coming City was just one more experiment in the quest for the Modern City.

The Utopian Techno-Religion of City Planning

Yet, Ashley’s experiment in Zion tends to be left out of the urban planning narrative due to its religious utopianism and ultimate failure. Conversely, urban planners and landscape architects like Howler, Olmsted, and Burnham are hailed as visionaries and celebrated for their lasting influence. This difference says more about present perceptions of religion than historical realities.

As Stanley Buder has argued, Ebenezer Howard’s work was shot through with utopian ideals, and his career was set in motion only after his own spiritual experiences in Chicago. While living in the city from 1871-78, Howard grew close to the spiritualist Cora Richmond. Despondent over his flagging faith in God and humanity, Richmond convinced him “of life’s higher purpose and of the working of cosmic forces that were pushing humanity in the direction of altruism.” (11) Similarly, Francis Knight has observed that Howard’s now famous To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform was only published thanks to his ties with the spiritualist network. Howard himself attributed his Garden City idea to the supernatural, telling the London Spiritualist Alliance that “I knew then, and I know with still greater certainty now, that the idea exists in the spiritual atmosphere which envelopes and pervades the lives of us all.”

Howard was not alone. Daniel Burnham was raised in the Swedenborg Church, a sect founded on the teaching of scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. Burnham was keen to spiritualize his famous Chicago Plan, proclaiming that the “spirit of Chicago” impelled its citizenry to create the “very best conditions of city life for all the people.” Similarly, Frederick Law Olmsted developed a deep evangelical piety in his youth, which was cultivated through a close relationship with the well-known congregationalist minister, Horace Bushnell. A “great purpose” of his most famous work, Central Park, was to provide tired workers “a specimen of God’s handiwork.”

What ties Ashley to Howard, Burnham, and Olmsted is not just a belief in progress and the possibility of urban space, it was also the almost religious belief in the ability of cities to shape and give rise to a higher form of life. As Burnham reminded his listeners in 1910, “a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing asserting itself with ever-growing insistency.” In other words, the layout of streets and the placement of parks and utility poles have a power all their own, a power to shape and insist on a particular vision of the future.

Thus, Ashley could claim, in full confidence, that “The carrying out of sanitary laws is sure to produce a higher and better condition of health, and therefore a higher standard of Christianity,” and “the first necessity, therefore that confronts us in the occupying and building up of a Model City, is to erect the bulwark of cleanliness.” Proving his belief, Ashley published detailed analyses on the “Question of Sanitation” in the Zion Banner, a periodical dedicated to the city. In column after column, Ashley gave lengthy, well-researched accounts of the latest research on waste disposal, the correct use of alleyways, and the principles of landscape architecture.

What Ashley and his peers understood was that urban planning is not just the polite and logical ordering of a city. Instead, it is a grand technology, a mega-machine that seeks to shape the life of society itself. As Lewis Mumford observed, every urban plan is an experiment in utopia, an attempt to project the “pattern of an ideal community” onto a real one because this projection tends to “warp our conduct in conformity with that pattern” and enable us to “overcome the momentum of actual institutions.” Though a city plan may begin as a utopia, it may also create one, in time.

This firm belief in the power of planned space to create a renewed form of social life is what anchored Zion, Chicago, and New York. In a very real way, Chicago’s urban plan was no less religious or utopic than Zion’s, nor was Olmsted’s Central Park less ardent and faith-filled than Zion’s Temple Gardens. They merely sought different ends. As Chicago and Central Park sought divine beauty and civic responsibility, Zion chased after spiritual purity and end-times prophecy.

Of course, in their utopic visions, each urban planning experiment experienced a degree of disappointment. Chicago’s fairgrounds burned, Central Park became a breeding ground for invasive species, and Zion went bankrupt. Urban planning is a powerful technology, but—as with any technology—its outcomes are not as easy to predict as its champions would suppose.

Ashley believed that clean streets would make clean souls in the Coming City, but those streets would have far less to say about Zion’s legacy than other technologies that would call the city home.

[This is the second part in a three-part series, that delves into the story of Zion, Illinois, and its founder John Alexander Dowie. This series explores the oft-misunderstood relationship between charismatic Christianity and modernity. Click here to read the first part. ]