Preface

I am currently in the third year of my PhD program in history, which means I am studying for my comprehensive exams. To non academics, this is a time when one reads more than is possible, attempting to retain as much as one can. At the end of the process, four professors will test me to ascertain if I am qualified to be called an expert in the four fields I am studying. For me, these fields are Colonial American History, 19th Century US History, Native American History, and Native American Literature. As I was frantically considering what to post here between reading the aforementioned mountain of books, I thought I might share with you a review essay I wrote as I was putting together my lists about a few books that while not representative of my studies, per se, are nonetheless interesting enough to discuss and focus on the Indigenous Intellectuals I study. Hopefully, dear reader, you will enjoy what follows.

“A form is simply something which allows something else to be transported from one site to another. Form then becomes one of the most important types of translation. To provide a piece of information is the action of putting something into a form.” ~Bruno Latour

“Sovereignty is when I speak my language” ~John Ridge, as written by Mary Katherine Nagle

Introduction

In this essay, I review The Life of William Apess, Pequot by Philip F. Gura; Assembled for Use: Indigenous Compilations and the Archives of Early American Literatures by Kelly Wisecup; Speaking for the People: Native Writing and the Question of Political Form by Mark Rifkin; and Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast by Ryan Carr. One volume considers larger collections of Native intellectual writings as archives and collaborative collections. Another looks at four distinct thinkers as an avenue for understanding relationality between individual representatives on Native nations, their communities, and the settler public. While the remaining two books are in-depth studies of particular intellectuals, their writings, and their contexts. Importantly, although often endorsed by historians, none of these books is written by a historian by training. Three of the authors reside in and hold terminal degrees in English while the third holds a doctorate in American Civilization and is spread between American Studies, English, and Religion. In a sense, this is unsurprising. Intellectual history has been on the outs within the guild for at least a decade. Most attention paid to what we might traditionally think of as intellectual history has come from scholars of literature and religion. As part of my review, I attempt to understand why this has been the case and what we may have lost in the process. Here I will consider each book briefly, in order of publication, on its own before turning to a synthetic analysis of the works and where they might guide future research and writing. Here I will make use of a panel I attended at a recent Ohmohundro Institute conference on “The Future of Vast Early America.”

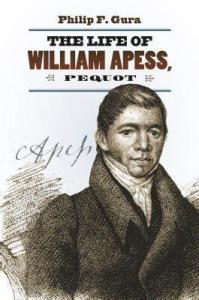

The Life of William Apess, Pequot

Many, including Robert Warrior, assert that William Apess was the most important Native intellectual before the twentieth century. He was the most published Native author and spoke publicly with a fervor that shocked and awed white audiences. He has also been radically understudied. This short volume by Gura describes Apess as a theologian/pastor, intellectual, and social reformer. Despite this, until the 1990s, he remained almost entirely ignored by the academic community. His early life was quite tragic, including abuse and abandonment from parents and grandparents before being placed in the equivalent of foster care. After suffering abuse at the hands of both biological and foster families, Gura argues that “Christianity taught Apess to resist the self-loathing such treatment engendered.” The greatest strength of William Apess, Pequot is Gura’s incredibly deep knowledge of both the print and intellectual culture of New England as context for the paucity of sources directly related to the man himself. Particularly, Gura’s description of the debates between pro and anti-Native newspapers during the Mashpee controversy immerses one in granular details of the controversy. His understanding of Methodism in all its complexity at the time provides helpful perspective for understanding how Apess navigated the theological and practical waters of denominational life. More time might have been spent on Apess’s wife and the few sources we have from her as well as the small controversy over his death and its mirror in the death of David Walker. Additionally, although Gura does not focus on it, it is worth noting in the list of 48 books which Apess owned, a volume by Hannah Moore, a prominent British Abolitionist on spiritual and societal reform is included. This speaks both to Apess’s international perspective and his focus on social reform as a person of mixed-race ancestry. The book easily accomplishes Gura’s goal of presenting a “straightforward” account of Apess’s life in order to make him more accessible and recognizable as a crucial figure in the Early American republic.

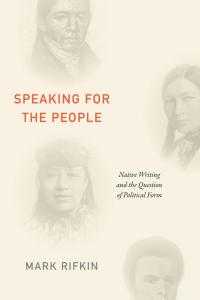

Speaking for the People

Mark Rifkin’s Speaking for the People, presents the most political account of Indigenous intellectuals among the volumes considered in this essay. Four such thinkers are considered. Alongside Apess, Rifkin introduces us to Elias Boudinot (Cherokee), William Apess (Pequot), Sarah Winnemucca (Paiute), and Gertrude Bonnin/Zitkala-Ša (Yankton Dakota). Using theoretical concepts propounded by Audra Simpson and Glen Coulthard, Rifkin analyzes these figures and their writings while particularly asking “Can refusal—the repudiation of settler frameworks operating on their own terms and toward their intended ends— dwell within what may look like the pursuit of recognition?” In a nineteenth century context, his answer is often yes. Throughout the volume we observe Rifkin’s four native intellectuals navigate the “dialectics of refusal and recognition.” Moving beyond recognition, Rifkin asks how his figures represent larger political groups both in the sense of acting as a proxy as well as creating a portrait of that group for a largely non-native audience. Here Rifkin argues against any sense of “authentic” Native-ness. For instance, many have looked at Elias Boudinot as being inauthentically Cherokee because he eventually signed the Treaty of New Echota, agreeing to Cherokee removal. By contrast, John Ross is often seen as more “authentically” Cherokee because he continued to resist removal. Rifkin argues we should actually see these differing strategies as distinct means of carrying on Cherokee-ness neither of which is more “real” than the other. To assume one is more authentically Cherokee or Indigenous is to limit Native cultures according to their legibility to white audiences. Although it would have been difficult, attention to the difference between Boudinot’s Cherokee language and English language writings could have bolstered the case Rifkin makes for Boudinot as continuing in Cherokee-ness. In many ways, Rifkin seems to see himself as responding to Lisa Brooks’s Common Pot, which he believes takes Native writers at face value without sufficient care or attention paid to the manner in which they are catering to the Settler imagination. While this may be a valid critique, it does at times seem shallow and to be comparing the incomparable as Brooks volume sits squarely in the eighteenth century compared to the nineteenth and even verging into the twentieth centuries where Speaking for the People occurs.

Assembled for Use

In Assembled for Use, Kelly Wisecup attempts to juxtapose Native texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with contemporary settler archives. This allows her to contrast how one might read and make use of these parallel sources for writing about the late colonial period all the way through the 1809s. The texts she asks her reader to attend to may at first appear uncanny. As she remarks early on, asking, “what… might [we] learn by reading texts long assumed both to lack readers and to elicit use rather than reading”? Hence, she looks at texts such as a collection of herbal remedies and recipes arranged by Samson Occom and the sue of quotations in John Ridge’s correspondence. These texts could even be considered utilitarian, but in Wisecup’s hands, the herbal recipes demonstrate how Occom healed and held together his community. Ridge’s quotations demonstrate… While Pokogon’s birchbark book reveals a materiality centered in an environmental critique of colonialism. Even these texts, which are more legible and seemingly prepared for the colonial archive “do important work on the page” and this “transforms narratives of non-reading and Indigenous objects of collection and study into one[s] of creative making, recontextualizing, and using within Native communities” Two categories of “reader” and “user” prove important for making sense of her project. The first represents a colonial observer audience and the second an indigenous audience which may or may not be literate, but is still able to make use of the given text. In short, by centering afterlives and unconventional archives, Wisecup seeks to destabilize colonial understandings of Indigenous texts. As she writes in her conclusion, The making, uses for, and circulations of Indigenous compilations expand our understandings of the hands that made early Native literatures, allowing us to recognize the relations among people already familiar in literary histories and those absent from such narratives but significant as requestors of healing, senders and readers of letters, singers of hymns, sewers of makaks, speakers of dialogues in an Indigenous language, and tellers of histories”

Samson Occom

Samson Occom was the first Native person to be ordained in the Christian church. History has tended to view him simply as a Native man who for all intents and purposes became white. According to this view, his various writings hold no particularly strong Indigenous perspective, nor do they attempt to resist colonialism or white supremacy. Ryan Carr challenges these perspectives in his meticulously researched recent biography. Here Occom becomes a multifaceted and radically complex figure who worked to create change under a veneer of supporting the status quo. In many ways, Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast should serve as a model for what engagement with and seriously considering early Native intellectuals look like. Not only is the introduction written by community members from Occom’s Native communities, but Carr in his research also discovered previously unknown texts owned, annotated, and written by his subject. Each of these pieces allows him to meticulously construct Occom’s theology, its political implications, and his tragic personal life.

In this way, Carr can also be seen as following the critique Wisecup has asked literary scholars to make in interrogating the archive. And indeed, Carr cites both Wisecup and Rifkin in sections considering archives and their legacies.

Carr presents three arguments in his argument about Occom: first, that Occom should be understood as a “traditionalist who sought to perpetuate rather than abandon Indigenous life ways…” Second, to protest the assumption that “Occom’s writings on religious topics were conventional, conformist, and/or derivative” of his Euro-American interlocutors. Finally, Carr argues that “Occom used evangelical discourse as a means of practicing his traditionalism in public.” I find Carr’s project remarkably compelling, and in several senses, it represents the cutting edge of Indigenous intellectual and religious history, practicing the methodological promiscuity urged on by Jean O’Brien and others. In addition to discovering previously unknown sources, including Occom’s personal, annotated copies of several works by Jonathan Edwards, Occom is displayed as the cosmopolitan figure he was. Carr puts a strong emphasis on his international ties and connections as well as the time he spent in British Isles. A representation of the ways in which he lives across boundaries is demonstrated in one of his school books where across seven pages and three languages, he wrote his identity: “Samson Occam Am Indian of Moyauhegonnuck Jure Hunc Librum Tenet.”

Carr presents three arguments in his argument about Occom: first, that Occom should be understood as a “traditionalist who sought to perpetuate rather than abandon Indigenous life ways…” Second, to protest the assumption that “Occom’s writings on religious topics were conventional, conformist, and/or derivative” of his Euro-American interlocutors. Finally, Carr argues that “Occom used evangelical discourse as a means of practicing his traditionalism in public.” I find Carr’s project remarkably compelling, and in several senses, it represents the cutting edge of Indigenous intellectual and religious history, practicing the methodological promiscuity urged on by Jean O’Brien and others. In addition to discovering previously unknown sources, including Occom’s personal, annotated copies of several works by Jonathan Edwards, Occom is displayed as the cosmopolitan figure he was. Carr puts a strong emphasis on his international ties and connections as well as the time he spent in British Isles. A representation of the ways in which he lives across boundaries is demonstrated in one of his school books where across seven pages and three languages, he wrote his identity: “Samson Occam Am Indian of Moyauhegonnuck Jure Hunc Librum Tenet.”

I am less convinced by Carr’s argument for Occom’s “traditionalism.” It seems clear that Carr understands himself to be defending Occom’s indigeneity against those who see his move to Brothertown as indicative of a shift toward adopting an overarching Euro-american mindset or worldview. Here Speaking for the People might have proved useful. I am quite skeptical that Occom was a “traditionalist” in any sense that word is used in religious history. Jaroslav Pelikan, the theologian and church historian, once remarked that “Tradition is the living faith of the dead. Traditionalism is the dead faith of the living, and I should note that traditionalism is what gives tradition a bad name.” Carr continually makes the point that Occom sought to use what he learned from Euro-Americans, particularly the transatlantic evangelical version of Christianity in order to reinvigorate his own communities’ lifeways. Occom often referred to this as “Our reformation.” In this sense, he was closer to Derrida’s original understanding of deconstruction as the taking apart and putting back together of a thing which one loves to ensure its continuance than he is to traditionalism. I worry that any claim towards “traditionalism” falls into the same conflict over authenticity that Rifkin demonstrates is both fruitless and an imposition from the white gaze in a Cherokee context. At his best, Carr clearly means something similar to Rifkin’s claim that there can be parallel, non-competing authenticities within Native communities. Despite this minor critique, Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northwest represents an important step for scholarship as Carr takes up the challenges brough to the field of Native Studies by books like Brooks’s Common Pot, Wisecup’s Assembled for Use, and Rifkin’s Speaking for the People.

Synthesis

The conversation between these books and their authors is complex to say the least. As mentioned, Carr cites Wisecup and Rifkin. Neither Wisecup nor Rifkin cite Gura; although Wisecup does reference Rifkin. Although, in a move that Gura would no doubt approve, Rifkin argues that Apess’s writing does not “so much prove Native sovereignty as presume it” Carr makes similar claims in defending Occom’s writings against those historians who see him as capitulating to the Euro-American imagination. It is also clear that Gura published at least six years before any of the other three. The explosion of literature in Native studies between 2015 and 2020 cannot be overestimated.

Another sense that draws these books together is their shared Latourian project of turning matters of fact (namely books as objects) into matters of concern (books/collections/pen strokes as things in a Heideggerian sense). While I think only Rifkin and perhaps Wisecup think of themselves as pursuing such a project, the care with which each of these authors observes what might in the past have been considered minutia demonstrates their perhaps unconscious presence in such work. Latour describes this phenomena as “What the etymology of the word thing—chose, causa, res, aitia—had conserved for us mysteriously as a sort of fabulous and mythical past has now become, for all to see, our most ordinary present. Things are gathered again.” In the post or metamodern world, we have begun again to find ways to understand the world around us as “enchanted” to borrow a commonly used theory word. However, it is important to note that since Native Americans were never allowed to be modern, in importance ways, their study never became fully removed from pre-modern understandings of reality and interconnectedness.

Provocation and the Future

As I think about the disconnects over religion, archives, and other problems between these books, part of the issue at hand appears to be a realization I had as I was thinking about the endorsements and acknowledgments from these books. I think this disconnect originates from the dual origins of NAIS. The two groups of scholars who came together to form the guild were largely anthropologists and theologians with a few Western historians. Thus, there is to this day an emphasis on one genealogy of Native history or the other, following ethnohistory and anthropology on the one hand and the dichotomous one primarily in religious studies and, sometimes messily, in English who follow the theologians. Vine Deloria, Jace Weaver, and Robert Warrior all received PhDs in Theology. These were the academic waters in which they learned to wade. Thus, they have a fundamentally different set of tools and means of looking at the academic world.

In thinking about all four of these works, I am broadly concerned with what moving the scholarly discourse around these figures into a broader complexity and knowledge looks like. In the most recent “state of the field” roundtable, The Society of American Intellectual history made this point: “Thus the individuals who would be the principal focus of intellectual historians would be those who think in public about matters of public concern.” While this article is over a decade old, it still raises problems for me here. Which public and whose concerns? In a sense, this question was raised parallel to intellectual history by Bruno Latour in his essay “Why Has Critique Run Out?” Latour answers his own question by demonstrating the limits of criticism as a skeptical taking apart, emphasizing instead the need for a positive project of criticism.

An example may prove useful. Beginning with Black Puritan, Black Republican in 2003, there has been a sub-genre of Black religious intellectuals studied in American Religious History. The Black church was one of the few avenues open for intellectual inquiry and output even in the North, prior to abolition. Scholars like Steven Harris and Jan Stievermann are expanding this category even now to demonstrate the depth of African-American political and theological thought during this period. There seems to be no major movement to separate these two facets of the African American intellectual tradition. It is confusing then why in the same period, when the two subjects seem inseparable except for the emerging White enlightenment thinker, we would divorce them for Native intellectuals as Rifkin and Wisecup tend to. As Doug Winiarski has noted, there appears to be an ongoing “Ontographic turn” among theorists. “Its leading lights include Bruno Latour in science studies” among others, such as Jane Bennet, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, and Martin Holbraad. Winiarski describes this turn as taking seriously the world as inhabited and experienced by those who still believed in “dreams, trances, and visions. Where God spoke directly to ordinary people in an everyday voice…and where white children spoke in unknown Indian tongues…” Why should we not also take such phenomena seriously in Indigenous intellectual and religious history during this same period of vast early America? Native Americans, even the most educated were still far removed from Enlightenment understandings of religion and spiritual phenomena. It seems to me that taking this sort of perspective, like Wisecup look seriously at Native writings as created for both settler and Indigenous audiences only grants us a broader scope in which to see and understand those whom we study. As Robert Orsi has written, “The alternative to historiography without gods is one that allows another reality to break into history and theory, not to destroy them but to enlarge them.”

Works Cited

Bender, Thomas. 2012. “Forum: The Present and Future of American Intellectual History, Introduction.” Modern Intellectual History 149-156.

Carr, Ryan. 2023. Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gura, Philip. 2015. The Life of William Apess, Pequot. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2004. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 225-248.

Nagle, Mary Kathryn. 2020. Sovereignty: A Play. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. 1984. The Vindication of Tradition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rifkin, Mark. 2021. Speaking for the People: Native Writing and the Question of Political Form. Durham: Duke University Press.

Winiarski, Doug. 2023. “Early American Religious History in the Ontographic Grain.” Ohmohundro Institute. Williamsburg: N.A. 1-11.

Wisecup, Kelly. 2021. Assembled for Use: Indigenous Compilation and the Archives of Early American Literature. New Haven: Yale University Press.